Do creator fans move from YouTube to streamers and TV?

It can be a bit of a tricky dance at times writing this newsletter. My aim is to demystify the internet for TV & film producers; to get beyond the noise and share information and case studies that might in a practical way help creative entrepreneurs find opportunities and plot a path in this disrupted environment.

In that goal, there is always a risk of sounding too much like an evangelist, where the complexity, challenges and financial realities are glossed over. This process of glossing can cause eyebrows to be raised and make experienced production company owners wonder if the world of online platforms and direct to consumer is a little too good to be true. Equally, when talking about many of the challenges that are out there on the internet, it can encourage people to retreat into the known TV and film worlds when this is a time of both opportunity as well as turbulence for us all.

The direct to consumer market offers a way for TV production companies to build their own audiences, reinforce their development process, establish new IP, enable brand relationships, and create new revenue streams. And this has the potential to reinforce a TV production business, rather than undermine or be parallel to it. It can also perhaps act as a hedge in a turbulent market, where having a route to audiences (and everything that comes along with that) is an asset for those with IP and stories to tell.

However - and this is a big however - it is hugely challenging, and there is much about how TV production businesses function that runs counter to the direct to consumer model. Frankly, if this was easy, then everyone would be doing it, and I wouldn’t be writing this newsletter.

We all know how profits are made via TV, which are more predictable and often larger than those made in the direct to consumer market. When looking at this new space and trying to evaluate revenues (never mind profits) it can be difficult. Not only does each creator business run its own distinctive strategy, they are also private companies so very little information is shared. We are left trying to extrapolate from particular datapoints, or titbits of information to get a picture - but it is never complete and might be misleading.

One of the core ways of making money online - advertising - is in constant flux both across the market, on specific platforms, within niches and genres, and for individual channels too. So a big part of the job of working online involves the constant monitoring of these fluctuations for how advertising is performing on channels, and also explains why revenue diversification is a big part of many/most creator businesses to try to find more stable sources of revenue and reduce exposure to the vagaries of the ad market.

Then there is the tricky issue of the data itself. In terms of subscribers or followers, there is the natural human reality where a selection of these won’t be active users any more: they no longer use that account or platform, or indeed, they might have passed away in real life. In addition, running paid campaigns to boost content and channels to potential audiences is a common practice.

Beyond that, there is the issue where the performance data itself is unreliable. Each platform is in its own constant battle of whack-a-mole trying to remove those who are gaming the system. Equally, what constitutes legitimate versus unacceptable channel building techniques is a moveable feast. After all, a key part of the sell to users to become creators is this ability to build an audience and make money. So it is hardly a surprise that many people do just that by riding whatever is the current trend, spinning up channels and grabbing revenues, say by using AI to generate faceless channels, as an example. Dipping into the conversations these people are having online, and you can see that many are aware they are in a dance with the platforms - trying to stay on the right side of legitimacy, while also anticipating that a crackdown might come and they’ll lose their channels.

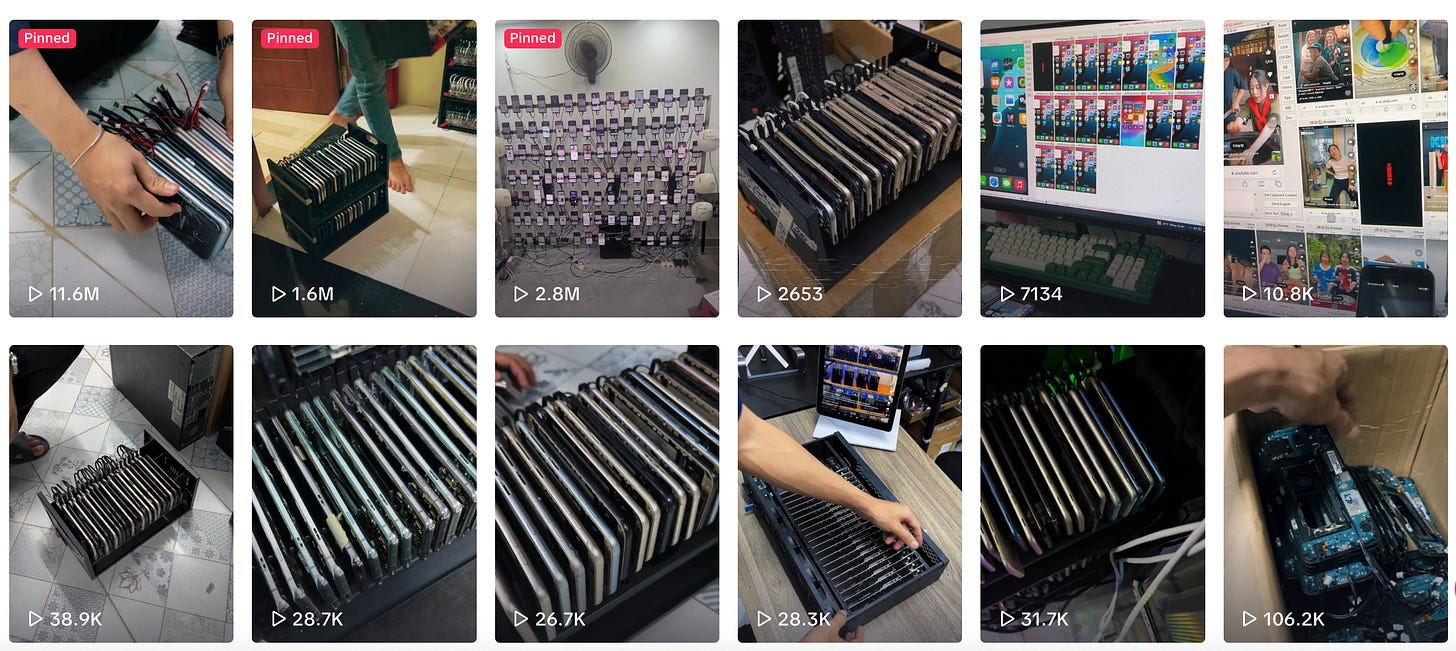

For others, this type of traffic building comes in a much more industrialised form. Test environments are a routine part of website and app development - making sure whatever app, website or service that is being built withstands various traffic loads and conforms to the technical requirements of all the various operating systems and devices.

However, these device farms can be used in a whole host of other ways to bolster traffic, subscriber numbers, views, likes, poll answers and so on. On TikTok, there are operators of phone farms offering their services, such as the one below based in Vietnam, which specifically highlights how using their phone farm ‘maximises your profits’ and ‘keeps earning while you sleep’.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

All this leads to a general unease about what is real and what isn’t. This can cover everything from views, likes, comments, trending topics, virality and so on. Indeed, the challenge around bots, content and traffic farms have been a constant theme for those working in the internet going back to its inception. This post from

is worth your time documenting this issue:I’ve been meaning to write more on all this complexity, and then this week

wrote this piece below where he aims to arm his readers with the tools to be able to spot hype and puffery, especially when someone (or something) is popular in one domain, and then swaps to another:In today’s social-media-fueled news cycles, herding around given narratives happens faster and at a greater velocity than ever before. Even in our little niche—entertainment industry/entertainment business strategy—trends get hyped well beyond what the actual data supports.

ESG then goes on to highlight the familiar trend of creators going to streamers, saying:

Since MrBeast is the undisputed top creator on YouTube—he has 439 million subscribers—any other creators (who are also multiples less popular) who migrate from YouTube to streaming will see results that are multiples smaller than his already average viewership. Indeed, this is why most creators who have gone to streaming have missed the charts entirely. For example, Charli D’Amelio’s show on Hulu (the largest TikToker in the world), Call Her Alex on Hulu (she keeps getting headlines saying she’s building an “empire”), Prime Video’s Overcompensating starring Benito Skinner, HBO Max’s Paul American starring Jake and Logan Paul, and Pop the Balloon Live! on Netflix.

At some point, he’s said he’s going to turn his attention to hype and the creator economy, which will be well worth reading.

In the meantime, I’m conscious I’ve written quite a lot about these types of creator/streamer deals, without following up on how they performed, especially in relationship to the audience and footprint on their own channels. So to pick up that baton, here are a few thoughts.

For streamers and creators, they might have a range of measures of success, in a similar way to TV and how that relates to particular advertising or sponsorship deals (“it did well in the demo” or “it outperformed slot average with youngs” and so on):

For example:

Territories and demographics - particular shows might be being commissioned to reach specific territories and audiences, and so while the overall numbers might not be stellar, if it did well in specific country or with a particular audience, then that might constitute a success

Testing something new - these types of creator deals in general, but also things like Pop the Balloon Live as Netflix is fairly new to live

Upselling something else - obviously for subscription streamers this translates to either taking out a new sub or not churning. For creators, it might be a brand deal, or a click to buy something, purchasing tickets or signing up for a newsletter and so on.

Having said all of that, the blunt measure of views gives us something solid to hang on to and keeps us all in check. Even so, it is tricky to then try to make comparisons between the different platforms, not least because how YouTube categorises a view is not the same as Netflix, and therefore simply taking the views from the Netflix ‘What we watched’ report and comparing it to views on YouTube is not to compare like with like.

As

has explained in the introduction to her H1 2025 Netflix Kids Content Performance Report that is hot off the presses - I’ll write more about it next week, but it is essential reading for anyone wanting to understand the kids market, which also has big lessons for the wider content sector:Views is Hours Viewed divided by the duration of the content. This is a revised metric released by Netflix from H2 2023 onwards in an attempt to level out the playing field of the rankings for individual seasons and movies across genres and formats. It does not constitute reach or unique views of a piece of content. It is also somewhat suboptimal when considering kids content in particular, where repeat watching is a known, in-built behavior.

So you can see the challenge trying to compare like with like when creators move to streamers. Using The Sidemen’s Inside series 2 as an example, the Netflix report says it had 2.4m views, however that doesn’t mean 2.4m accounts watched the show, it means there were 17m hours watched divided by the total run time of 7:12 - so eight episodes each in duration of between 36 minutes to 60 minutes.

Beyond this comparing apples with oranges caveat comes a few more health warnings when making comparisons:

The YouTube numbers are total views for the series which have often been live for a considerably longer period of time in comparison with the Netflix series all of which launched within the last year

YouTube’s Sidemen Inside is series 1, and Netflix carried series 2, plus it wasn’t available globally

Pop the Balloon on YouTube has over 60 episodes, so I’ve taken an average of 3m views per episode, for seven episodes (which is the number that went out on Netflix). Plus the Netflix series had this live element which the YouTube series didn’t.

So with a heavy health warning here are some rough view numbers comparing some of the creator shows on YouTube and then on Netflix:

The Sidemen’s Inside - YouTube series 1: 73m views, Netflix series 2: 2.4m views

The Amazing Digital Circus - YouTube: 896m views, Netflix: 16.8m views

Pop the Balloon Live - YouTube: 21m views, Netflix: 8.7m views.

Will Netflix be happy with these numbers? As always, the answer is… it depends.

The Amazing Digital Circus was an acquisition for Netflix, and while the numbers aren’t anywhere near the giddy heights of how the show has done on Glitch’s own YouTube channel, it appears to be a solid performer putting it in the top 130 shows in H2 of 2024, and top 350 shows in H1 2025 (I’ve combined those view totals to give the 16.8m above). So perhaps Netflix will view this as a positive performance. This was a non-exclusive acquisition for Netflix, and will have cost them significantly less than those that are original commissions. Plus, people watching it on the streamer arguably wouldn’t be Glitch fans migrating from YouTube, as a) they’ve already seen it and b) the YouTube experience has the community and chat-along experience that Netflix doesn’t have. Interestingly Glitch has inked another acquisitions deal, this time with Amazon and for different titles.

In terms of these types of creator acquisition deals, I’m really keen to see how the Alan’s Universe catalogue performs on Roku.

Moving on, Pop the Balloon Live feels like it was an experiment with live as well as how it was scheduled and marketed. I’d love to hear or read more about how it was perceived within Netflix for these reasons.

Sidemen’s Inside had 2.4m views which put it around 1,000th on the list of most viewed titles in H1 2025 on Netflix. Series 1 (which is non-exclusive on Netflix) had 200,000 views. In an (apples and oranges) comparison, on average on YouTube, each episode of Inside series 1 had around 10m views, totally 73m. Considering the size of their fandom, it is fair to assume Netflix would have liked a bigger audience, especially with the recent success of their smash hit Wembley football match (perhaps Netflix should live stream the next one?). Final point, I don’t recall seeing much advertising for the series (certainly not on the side of buses and so on that Amazon invested in for Beast Games), so I wonder if more marketing would have helped.

As for MrBeast and Beast Games, this didn’t deliver a huge audience for Amazon (especially considering the reported $100m budget), so that anticipated shift of his audience to the streamer doesn’t appear to have happened in reality, even with the amount of advertising welly put behind it.

An adjacent point about MrBeast, which is the report in Bloomberg recently about how Beast Industries is looking to be more focussed on cost control after losing money over the last three years. As

said:SO: Mr. Beast’s BEAST INDUSTRIES has lost money in each of the last 3 years, including a -$110M result in 2024 alone, according to a new Bloomberg profile — essentially the video revenue losses exceed the candy / consumer products profits. The company employs about 350 folks (200 in video).

The Bloomberg profile is worth your time:

To pick out a couple of interesting details. Firstly around how much money is lost by his video operations:

Beast Industries is hemorrhaging money … The viral videos account for all of it, overwhelming the profits from Feastables. Donaldson has been spending between $3 million and $4 million on every video he produces for the main YouTube channel, most of which lose money. In 2023, Beast spent $10 million to $15 million shooting videos it never released to the public because they weren’t up to its standards.

Secondly the ambition for some sort of scripted franchise universe:

[CEO Jeff] Housenbold envisions building out a MrBeast cinematic universe, and he’s put together a writers room that’s sketched out a “world bible”—the backstory. He’s reluctant to share many details but says they’re developing seven or eight characters from a fictional planet that will inspire an animated series, a comic book, a TV show and toys.

And finally, this key insight into content volumes:

…much of the MrBeast strategy boils down to “Less is more.” Rather than produce 100 videos and hope one hits, he makes one video that he expects will get as many views as possible.

This diversification strategy is common amongst mega creators, where they are launching consumer goods, live events (although that has long been the case for influencers and creators), their own streamers and well as tech services, rather than relying solely on YouTube for revenues. It is also a similar strategy for creator businesses of all shapes and sizes, and I’ll write more about some examples soon.

Last thing - this is a great piece and interview on the state of the Google (and YouTube) ad market, if you’d like to have a deeper dive.

What producers need to know - #3

Here is the third of the 36 things I think producers should know to plan for the future, that I shared as three paid posts a few months ago. I’m sharing one per week for the foreseeable, and here is the third one:

The internet is all about direct to consumer

Knowing that the internet at its heart is about building direct relationships with audiences and the reduction in the status and power of gatekeepers, it follows on that building a direct-to-consumer (direct to audiences? Direct to individuals? Direct to fans?) relationship with people who love you, love your shows, and want more from you is big priority.

This can come in all shapes and sizes, and frankly, if your company already has a website, an Instagram account or a Facebook page, you are already building a direct-to-consumer offering – you just might not view it that way. And if you aren’t seeing it that way, then it is possible you aren’t (yet) getting the most value out of these channels.

While there are a couple of companies that can get away with being something of an enigma online (Bad Robot comes to mind), for most organisations, having a direct-to-consumer strategy is fast becoming business as usual rather than an optional extra.

What is direct to consumer in practice? Without knowing your company or you as a producer if you are individual, it is hard to give an exact answer. However, it can cover:

An email list or a newsletter

Social accounts on Instagram, Facebook, X, TikTok, Snapchat

A YouTube channel or channels

A website

An e-commerce website or presence on Amazon or other sales websites

An app

A paid subscription service

A podcast

Live events

Merchandising

Training courses.

For producers, direct to consumer is both an offensive and defensive strategy and increasingly will become essential to the extent I think in 2 – 3 years it will be business as usual for many production companies. To give a few more reasons why it is so important:

Direct to consumer acts a hedge so you have a route to audiences that you own (instead of leaving ownership of people watching your shows with networks or broadcasters)

You can make money from that audience

It creates a mechanism to test ideas and prove there is an audience for it that you can use to sell a concept elsewhere

It creates a valuable marketing channel for B2B projects (both with brands and commissioners)

It enables your organisation to understand this space by doing rather than in theory.

Before getting bogged down in thinking ‘oh no, I don’t have time or expertise to do all of that’, instead the first step is to take to heart why you should do this. What can come later is the what, how and when of your strategy.

And as I’ve said previously, deciding not to get into this space is not a neutral decision. It might be the right one for you and your company, however it doesn’t come without longer term consequences.

If you’d like the full set of 36 things I think producers should know, they are here:

What TV producers should know part 1 - this first post is about the market context and covers the external factors beyond our control

What TV producers should know part 2 - this second post is about what is within our control in how we can respond to the external market

What TV producers should know part 3 - this final post is about some practicalities to think about when planning for the future.

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Really interesting and useful, thanks for posting