Streaming profits aren’t replacing those lost by linear TV

The return of the HBO brand; are we about to see a shift at Warner Bros. Discovery; plus nervousness about Apple and its cinematic strategy.

This week, I’ve written about the following:

Declining linear TV profits not yet being replaced by streaming

Social teams at Warner Bros. Discovery having a whale of a time thanks to the announcement of the return of the HBO brand

The Sidemen launch a VC fund

Does disinformation present an opportunity for producers steeped in editorial standards

The trailer for Apple Original’s new F1 movie triggers nervousness about whether the tech giant will stay in the cinematic game.

And as always, send feedback - especially if there are particular things to want to know more about - hello@businessoftv.com. Please do share if you think any of your colleagues will find this interesting or useful:

Declining linear TV not being replaced by streaming profits

TV Grim Reaper - otherwise known as Bill Gorman, previously of TV By the Numbers - routinely posts a melting ice cube when tracking the declining linear TV business model and the lack of a streaming model to take its place, for example:

As various global entertainment businesses announced their earnings, he again highlighted the significant gap between linear TV profit margins and those of streaming. I did the table below, although a little warning around comparing apples with oranges as each company reports their income, profit margins and costs slightly differently. Even so, the general gist is clear, where direct to consumer (meaning streaming and VOD) simply isn’t close to the profits generated by linear broadcasting.

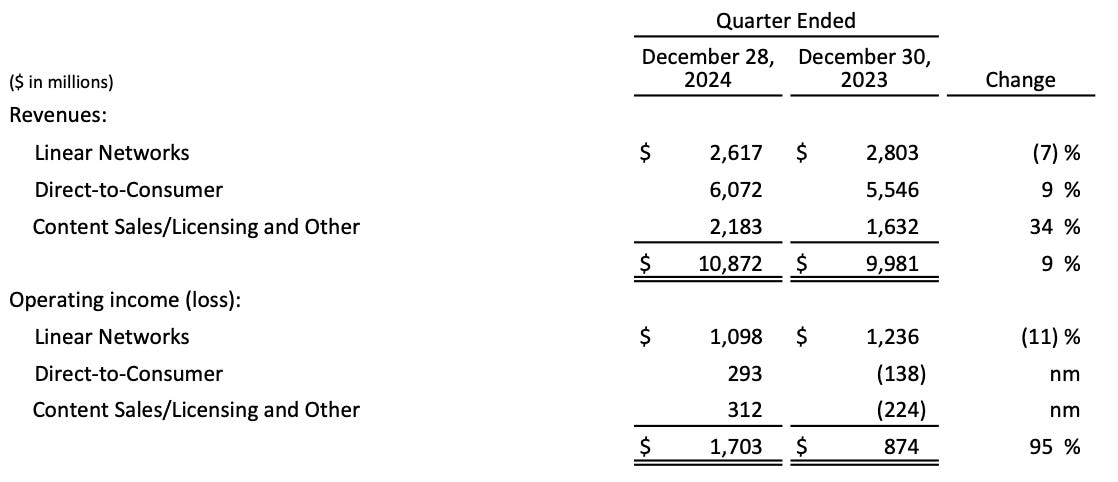

If you look at Disney’s quarterly results below, you can see the pattern - linear networks declined by 7% in terms of revenue compared to the previous year, and operating income down by 11%. But even so, this represented over $1bn in operating income and 35% profit margin. Now look at direct to consumer - up 9% in terms of revenue at $6bn, which is more than double the linear networks. However, only $293m in operating income and 5% profit margin.

There will be all sorts of reasons for this, but to highlight one important cost difference: Linear TV is a highly efficient and well developed technological and financial model because in super simple terms, how many people watch the transmission doesn’t change the distribution costs - they are fixed. In contrast, streaming platforms are a hugely complex technical feat, involving multiple different systems and a whole lot of engineering to ensure that each user’s chosen video can be watched without interruption or buffering, no matter where they are in the world. Some of these operating costs are variable. I’ve written previously about the economics of content distribution networks (CDNs) in streaming businesses:

This Streaming Media article explains a whole lot more about how tech infrastructure works and is worth reading if you’d like an introduction to this hugely complicated and expensive part of our world:

CDNs represent the largest variable operating cost associated with technology for most major streaming platforms. Third-party CDNs charge streamers based on the consumption of bandwidth in terabytes (TB). Thus, these operating fees scale with subscriber growth and are often built into average margin-per-user economics.

While some of the tech costs have come down since the early days of video on demand, the expenditure will remain for two reasons: firstly, because it actually costs money to run these services and distribute video content over the internet including servers, loading, energy, hosting, security, payment processing, ad serving and so on. And secondly, hosting and distribution is big business. Amazon Web Services (AWS) has over 30% of the global cloud business, and many of the big streaming platforms use them. You can see a graphic below that shows in 2021, Amazon’s total revenue was $469bn, the vast bulk of which was eCommerce, and a very small amount in AWS. However, of Amazon’s total operating profit of $24bn, 74% of it came from AWS.

In the most recent numbers, AWS profit margin was 38%, and made up 60% of Amazon’s overall profit.

Over and above this, some broadcasters and streamers have their own CDNs. YouTube, Amazon, Netflix and the BBC have built their own, starting at least 10 years ago (if not 20 years ago). This means for these organisations, while there are real technical costs to managing their own tech stacks, they aren’t having to pay for their video distribution to the likes of AWS, Microsoft or Akamai.

And it isn’t just the big players who have invested in this way. For example, in this profile of Efe Cakarel about Mubi being valued at $1bn, he makes this comment:

“We built our own content delivery network, our own encoding tool chains and our own streaming services,” he says. “But we estimate that it costs us 70% less for our infrastructure than those who rely on other platforms.”

So, when Netflix’s reports an operating profit margin of 27%, keep in the back of your mind that a) they have invested heavily in their own tech stack keeping their distribution costs as low as possible b) these costs don't work into same way as linear TV and c) for all those streamers without their own CDNs such as Channel 4, ITV, WBD, Disney and Paramount, their real costs are relatively higher and have to be paid to third parties like Amazon Web Services.

For these reasons, I do wonder if at some point we will see a network or a broadcaster pull the plug on their own streamer and instead publish straight to a third party where they can sell their own ads - say YouTube, Netflix or Amazon.

The latest goings on at WBD

I’ve not written much about the future of the various cable networks of late, as until something significant happens there isn’t much to be gleaned from the gossip.

However, this week came two movements out of the WBD lot: 1) The return of the HBO brand to the Max service and 2) more solid rumours that WBD were moving towards splitting off some of their assets.

HBO Branding

I’ve written about the treatment of the HBO brand in the past, and now it has been announced it is returning.

The WBD social teams were certainly having a field day with the announcement, and who can blame them:

Although personally, this one touched a nerve…

Peter Kafka of Business Insider made the following point:

…this is yet another acknowledgment that the thesis behind the merger of what used to be called WarnerMedia and Discovery hasn't panned out. The thesis was that combining HBO's programming with reality TV programming would make a streaming service with broad enough appeal to take on Netflix.

Or if you rather your analysis a tad more blunt,

said:The attempt to bury the HBO name — perhaps the strongest identity in entertainment — under some meaningless brandlet in hopes of finding a larger audience beyond the service’s passionate devotees — will go down as one of the most self-destructive acts of corporate hubris in modern times.

I think this situation matters more than just being a weird bit of corporate decision making, and perhaps there is something for us all to learn from it.

This journey from HBO Max > Max > HBO Max will have cost a lot. Anyone who has worked on branding or rebranding will know the effort involved in this activity, and there will have been significant costs associated not once but several times over the past few years. Indeed, even just the announcement of the re-brand involved the creation of multiple assets, including some featuring their top talent:

Another impact may have been the loss of subscribers, or potential subscribers: people who were unaware, confused or turned off by the Max proposition.

The other price WBD may have paid was an opportunity cost: where time spent on one thing could have been better spent on something else. And here, considering the state of both the market and WBD itself, it isn’t ridiculous to suggest that all of the teams within the company could have spent their time and skills on something far more worthwhile that the HBO/Max branding farrago.

Moving on to the second big movement related to WBD this week…

Potentially splitting up the company

Last July I wrote about the future of of the company:

Future of Warner Bros. Discovery; Apple TV spending rumours & latest on Netflix games for TV titles

At the time, I quoted Matt Belloni from Puck.News who summarised the (then) options for WBD:

“1) sell the company; 2) sell some assets; 3) merge, preferably with the home of a broadcast network; 4) do a streaming merger or joint venture; 5) stay the course; or 6) spin off the linear assets (and the debt) into a separate company.”

Business Insider’s Peter Kafka was slightly more blunt:

'“The theoretical plan … is to turn WBD into one "Goodco" — its (formerly known as HBO) Max streaming business and its Warner Bros. movie studio — and one "shitco" — all of its declining linear TV networks, including CNN, plus most or all of the $40 billion in debt WBD has taken on.”

As we know, spinning off assets is exactly what Comcast has done, and the new spinach has a name which is Versant. As this Variety piece reports:

Versant … will house TV networks including MSNBC, CNBC, USA and E! along with other media properties. There is an expectation that Versant will seek to build upon its portfolio by acquiring other properties. Comcast spun off the assets in a bid to focus NBC on broadcast and streaming, while giving the rest of its media assets a chance to eke out a new existence.

Therefore splitting off assets isn’t a new idea, and this week there was more indication that WBD is moving in that direction, with CNBC’s David Faber reporting: WBD is “moving towards…a split”. As an organisation they’ve also completed the restructure to create distinctions between the linear TV networks from studios and streaming. There remain a few obstacles in the way in trying to split out the linear channels from streaming and studios, which are explained in this piece below:

WBD’s recent results included some positive news: the global streaming business has added on 5m new subscribers in the first quarter this year, and 22m in the past year. In total there are 122m subscribers and according to Puck they anticipate they’ll have 150m by the end of 2026. Studios has also had a good run with The Minecraft Movie and Sinners both smashing it at the box office and outperforming expectations. Similarly, they’ve eaten away at the debt mountain, with Puck reporting:

As of March 31, WBD now has $34 billion of net debt, having paid down another $2.2 billion of debt in the first quarter. The WBD debt load has now been reduced by $21 billion in three years.

And looking forward the new Harry Potter series plus various movies in the pipeline are expected to do a lot of heavy lifting over the coming years.

Even so, for all of this, as outlined above, the gulf between the profits of linear TV and direct to consumer really matters, and it is hard to see how the streaming profit margins can be driven upwards towards the (previous) dizzying heights of the linear business in the next few years.

This is where the technical costs of running a streamer come into play. WBD has invested heavily in their tech over the last few years, including rebuilding the Max platform from the ground up. This article is worth reading to see the level of effort and complexity involved:

Even with such a huge amount of investment, it still isn’t enough to fund the building of their own CDN. As noted in the above piece, Max uses four CDNs — Amazon CloudFront, Google’s Cloud CDN, Akamai and Fastly. It also uses AWS as a primary cloud provider. The CTO is quoted as saying:

“In any given month, we deliver more than an exabyte worth of content, which is 1,000 petabytes a month, which is a big amount. And you cannot rely on just one CDN to do that.”

So here you can see the technical competitive advantage of YouTube, Netflix and Amazon, and how hard it is for other players to catch up. Not only did the investment in their tech stacks cost a lot (Netflix invested at least $1bn), it also took many years to develop.

The Sidemen launch a VC fund

When Jordan Schwarzenberger manager of Sidemen/founder of Arcade Group recently said on LinkedIn “…if I was running a VC fund…” it became pretty obvious that this is exactly what he should be doing.

And yesterday it was announced that Upside VC has been launched, with the strapline ‘The future of consumer is distribution driven”. They’ve already made 12 investments, and from first glance these are not content or creator businesses but rather apps and consumer packaged goods thus far (perhaps with creators promoting and marketing these products to their audiences).

For a while now, many working in the TV, film and creator space have been looking for what is often euphemistically called “innovative sources of finance”. Sometimes meaning brand or crowd funded but increasingly people looking further a field to get creative projects off the ground - so private equity or venture capital funds (I wrote about some PE funds investing in movies a few months ago).

It will be interesting to see if these sorts of movements remain focussed more on digital or real world products, or if they move into the content space.

Does disinformation present an opportunity for producers steeped in editorial standards?

There recently was a Disinformation Summit at the University of Cambridge, and the remarks of Alan Jagolinzer, Vice Dean of Programmes at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School are worth reading: he says the root of disinformation is international crime syndicates and mafia states taking over nations and running manipulative campaigns via social platforms that are not rigorously moderated enough by tech companies. And then cowardice amongst us all for not intervening. It is a short, bold and punchy analysis of the shape and nature of disinformation, and I’d urge you to read it:

Thanks to Richard Sambrook for sharing it on LinkedIn.

I’ve touched on issues around truth, disinformation and editorial standards online, largely highlighting the lack of regulation in online platforms, and the uneven playing field when comparing broadcasting to online compliance. The volume of disinformation - both from bad actors but also well-meaning but inexperienced or inaccurate creators and publishers - is already an issue, and will likely come under much more scrutiny in the coming years.

Over the years, it has not been uncommon for those working in the wild west that is the internet to downplay the importance of issues around the law, compliance, duty of care, editorial standards and the like. However, these issues have a habit of becoming increasingly important as markets mature: when scrappy upstart publishers and individual creators become media empires, then money flows, and legal trouble can follow as standards are expected.

For TV and film producers, I remain convinced that a) the trend for audiences to seek trustworthy sources will become more pronounced b) this presents a very clear opportunity for TV producers to apply their editorial and compliance rigour to producing content for online, and c) producers should consider positioning themselves in the creator and direct to consumer market as not only great storytellers, but also storytellers that can be trusted.

F1 Trailer release triggers nervousness around Apple and cinematic

The trailer for the glossy Apple Original F1 movie dropped this week. And although it looks like a great flick, there is a good reason to keep an eye out for whether it flops or hits, because as analyst Brandon Katz said: “… if it flops, Apple is likely done with theatrical, which is bad for the industry.”

The reason for the skepticism about its ability to turn a profit is because of the size of the budget - rumoured to be $300m. Last week

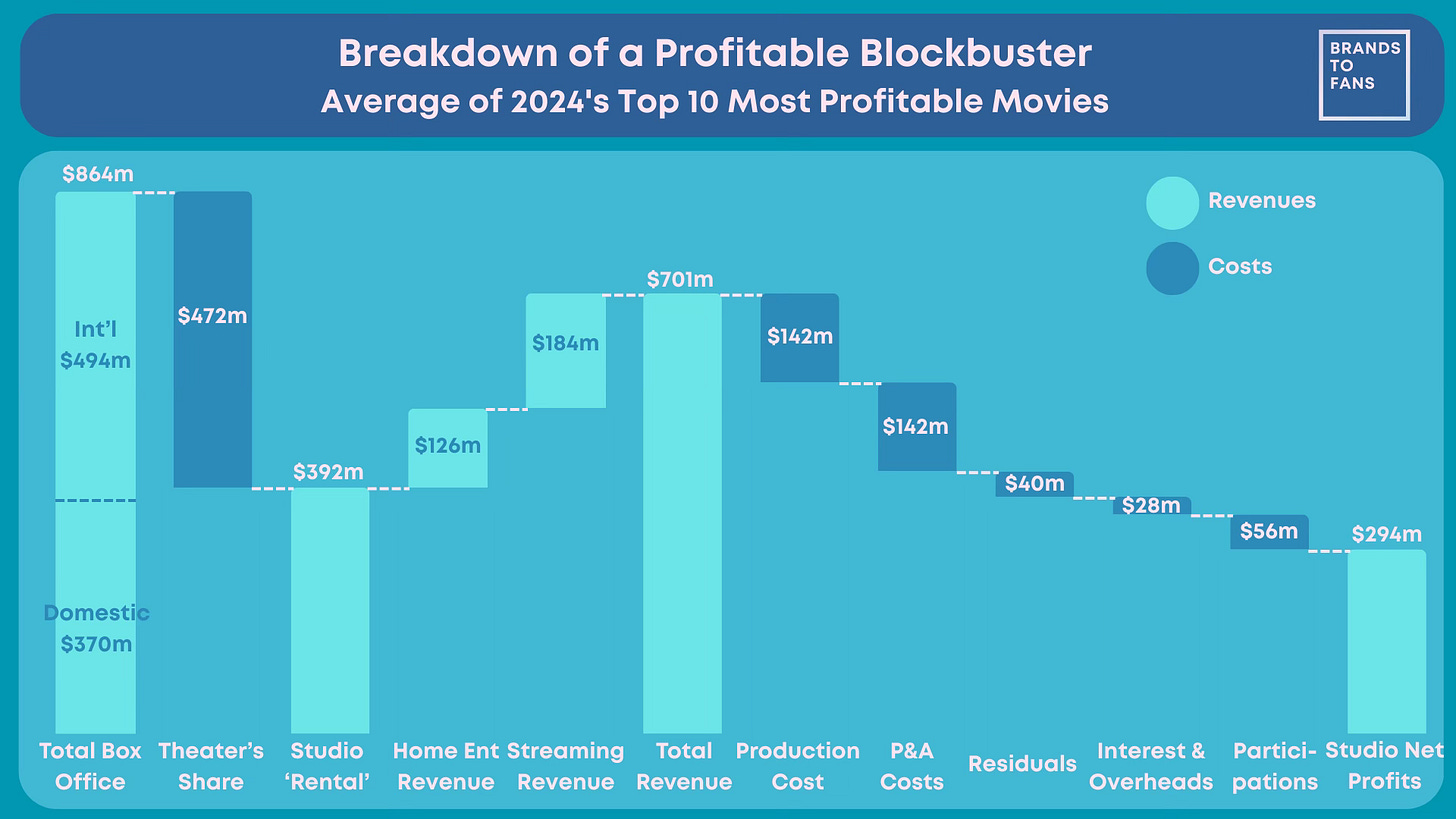

wrote a very useful post on a pet peeve of mine (and seemingly many others) which is when it is assumed that the production budget of films equate to the total costs and therefore anything above this number is profit.So using his breakdown graph above, you can see that the production costs for F1 are more than double the average of the 2024 top 10 most profitable films. Assuming the P&A (print and advertising, or marketing) costs are also doubled, then this film will need to do something around $1.6bn at the box office to generate a similar level of profit. Although caveat around the release schedule and forecasts for streaming and home entertainment (rental and DVDs) due to it being an Apple Original.

This might be a barnstormer of a film, but to generate similar profits as outlined above would require this film to be in the top 10 grossing films of all time (or when adjusted for inflation, the top 20). Not impossible at all, just a very high bar.

Looking at the last six cinematic releases from Apple, and you can see why commentators are wondering if continued investment in this area hinges on F1’s success. Of course, Apple will have its own internal ROI calculation that puts value on these films in relation to subscription numbers, and perhaps consumer product sales. Plus some of these films you can see had a very short cinema window before appearing on Apple TV+ (I’ve written previously about the growing awareness challenge for cinema - making potential ticket buyers aware of a film in the first place - and these short windows surely can’t help). Also, a health warning around Argylle - there are questions over what the production budget was, so I went for a conservative $100m guess rather than the $200m reported figure. I’ve also left out Wolfs, which had a tiny cinema window after much consternation over a Brad Pitt/George Clooney film being streaming only.

Even so, only two of these movies covered their production budgets via box office sales, and none generated the level of box office sales required to make actual profits.

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

To give an answer to your poll question : I checked other. My answer is:Ego. Because I don’t understand their strategy. They spend a ton of money on their shows and movies, but tell no one about them. This feel contradictory to a studios practice of promoting and marketing their hard work and expensive projects. Personally, I love their stuff. They feel more like HBO than HBO at times.

Thank you for the shoutout!