Trends which could impact TV and film production companies in 2025

Here's my (incomplete) list of what I'm looking out for in the year to come.

2024 was a year of tectonic plates shifting, and my inbox and social feeds are full of reflections of the year that was and predictions for what 2025 might, could or will bring. Rather than trying to predict outcomes, instead I thought I’d shared the big trends and themes I’m watching out for which I believe may impact TV and film producers and production companies if not in 2025, but perhaps over the next few years.

The list below is broad and covers everything from YouTube to ad-supported streaming TV services, M&A activity to innovative project financing models, Walmart buying a TV manufacturer to AI copyright and media regulation.

I’ve tried not to repeat in detail too many of the great 2025 predictions out there - although unsurprisingly similar themes do crop up. Here are some worth reading (a mix of paid and free):

- : 2025 Belongs To YouTube?

Alan Wolk on TVRev: Once More Into The Breach: Our Fearless Predictions For 2025

- : TV ‘25: Self-Financed Series and 3 More Market Shifts to Know

- : AI, YouTube, TikTok: How TV Producers Plan to Cash In in '25

AdWeek: How AI Will Impact the TV Industry in 2025, According to 15 Executives

- : Hello 2025 - 8 things to consider in the TV year ahead

- : The TV of the Future

So in no particular order, here are the things I’m looking out for in the year to come. Let me know what you think in the comments below.

YouTube and YouTubers continue to gobble attention

The growing army of millions of creators on YouTube - as well as all the other social platforms - are as a group grabbing the attention of viewers who previously only had TV channels to choose from. Or more accurately, TV, games, magazines, books and films.

The explosion in the number of creators and the share of audience attention that goes to their channels instead of professionally produced TV is likely to continue. While TV broadcasters and production companies have already used YouTube to distribute and market shows, few have stepped into the ring to become originators on the platform. Over the next year perhaps this will change and we will see more TV production companies launch original channels similar to those run by creators.

The most interesting bunch to watch will be all those TV freelancers who have spent much of 2024 out of work - will they consider making the leap to becoming a YouTube creator by focussing on their genre specialisms or niches? Indeed, much of the appeal of being a creator is the no barrier to entry and low levels of gatekeeping relative to TV, film and digital content where it is dependent on commissioners, brands or financiers to fund the production.

While it is easy to get into YouTube (and TikTok and so on), to succeed is hugely challenging and involves a steep but interesting learning curve, combined with hard work and a strong dose of luck. Knowing this, will 2025 see more TV companies and individuals successfully make this transition to become the new generation of TV/creator hybrids?

Creator economy continues to mature

The creator market will continue to develop and mature over the coming year. As by its very nature, it is messy, individualistic, fragmented and disparate, and therefore it is tricky to suggest broad brush themes. Even so, I’m keen to watch how trends develop in this sector, for example:

the further emergence of creators as individual media empires or brands

whether creators can continue to successfully bring and sustain their online audiences to TV or streaming shows - ones to watch will be the numbers on Amazon’s Beast Games once the dust has settled, plus Netflix’s deal with the Sidemen

how successful creators shift from flogging low value ‘merch’ to launching quality products that can compete with top retail brands

will advertisers put pressure on YouTube to improve its advertising experience in comparison with TV (Alan Wolk is worth reading on this point: Once More Into The Breach: Our Fearless Predictions For 2025)

whether revenues are enough to sustain the number of individuals entering and competing in this sector

the risk of burn out because of the demands of algorithmic publishing

how the various platforms deal with the growing trend of get rich quick and disinformation channels.

A little example of the maturing of this market was announced at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Vegas this week: Delta Airlines agreeing a deal with YouTube to make YouTube Premium & Music services free to loyalty programme members, which will also include a selection of YouTube creators’ content. It is this type of activity to look out for in 2025.

Compliance and regulation

Another key area for 2025 is around regulation and compliance, which has a knock on to production companies, broadcasters, online content businesses and more.

The announcement by Mark Zuckerberg this week to mega-pivot Meta’s moderation policies is a significant shift away from the approach of the last years, and should also be viewed within the context of big tech facing a whole host of legal and regulatory scrutiny including various antitrust trials for Google, never mind questions about TikTok’s ownership and the also wider issues over the responsibility for user generated material on social platforms. This is against the obvious backdrop of a new presidency with its own agenda and priorities.

As previously written about, there are several key known issues likely to arise over the coming months.

Firstly, Ofcom needs to specify which platforms will be covered by the Media Act of 2024 (the law to bring all mainstream video on demand services under Ofcom’s regulated content code) - here is a useful summary of how VOD services will be treated under this new act. At the moment, the act does not yet address which streaming or video-sharing platforms which fall out of its scope. By March, Ofcom needs to say whether services like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Apple TV+ will be covered (as they are 'TV-like' services); whether smaller VOD services will be included; and indeed if this will have any relevance to a platform like YouTube.

Secondly, the Baby Reindeer case is due to head to court this year (here is a useful legal summary, thanks to Prash Naik for sharing).

Thirdly, there are also the ongoing antitrust cases in the US, however, how this develops depends on whether or not there is a vibe shift with the new presidency.

Finally, as more creators sign big deals with platforms like Amazon and Netflix, it will be interesting to watch how compliance is approached and managed between two such different cultures and regulatory environments.

M&A for traditional TV networks

This is one area where any predictions (or frankly, any predictions I make) are likely to be wrong. Suffice it to say that change is afoot in the ownership of traditional TV networks, especially in the US. How this shakes out is anyone’s guess, but definitely one to keep watching as it is likely to have an impact on a whole host of UK-based TV businesses, including broadcasters, production companies and freelancers.

Obviously there is the Paramount/Skydance deal that is being worked through, and it is suggested it will be completed in Q1 or Q2 of 2025. If it goes ahead, there will be a knock on to Channel Five as part of Paramount’s stable.

And then there is Warner Bros. Discovery, which has been undergoing a reconfiguration that observers suggest is to make it more appealing for a sale (or alternatively, a sale of specific assets). Who could buy WBD is a great spectator sport: ranging from Comcast for the whole company, to Apple for certain assets like HBO. Again, another watch this space.

For the wider traditional TV market, there are questions whether various big tech companies will pluck off other assets where they complement their existing businesses, remembering that while cable TV may be declining, it still a money making machine.

There are always deals being done in the TV industry, some more significant than others. So the challenge is to work out which deals are genuine tectonic shifts in the future of TV, and which are more run of the mill, no matter how splashy. As an example, this week saw the announcement that Disney is combining its Hulu+ Live TV service with the streamer Fubo. This is significant as firstly, it is reflective that the big players need more scale in the market, both in terms of audience proposition (Fubo focusses on sports and news while Hulu+ Live TV is known for entertainment) as well as reducing the technical and operational costs of running individual platforms. And secondly, the deal sees the end of the litigation between Fubo and Venu, the proposed sports streaming service from Disney, Fox and WBD.

CNBC: Disney to combine its Hulu+ Live TV with streamer Fubo

Read more about streamers and how their tech stacks give them advantage.

Different strategies to increase time spent within a company’s ecosystem

A big broad battleground involves how various companies are competing to be the (or at least one of the) go-to brands to power more of our lives. As I wrote last year within the context of the streaming wars:

…it isn’t so much about winning the streaming wars and creating profitable video services, rather the bigger war is to own the whole media experience for users across the globe.

Through this lens, you can see how tech companies like Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Meta and Google are fighting to be the software, hardware and services ecosystem for audiences, as well as consumer electronics brands like Samsung and LG.

And so within this context, keeping an eye on how companies are launching new products or services to try to capture audiences attention is important.

In the last year or two various companies have announced streaming services or originals strategies such as Hallmark+ and Chick-fil-A. Walmart announced in January it will acquire Vizio, one of the top manufacturers of smart TVs in the US, and thus become a streaming aggregator as part of its continued competition with Amazon. As Variety+ reported in November, “Acquiring Vizio will let Walmart expand its connected TV ad business while entering the hardware game and retaining its retail power”:

Walmart is therefore well on the way to going toe-to-toe with Amazon as the “everything store” of streaming, with its own hardware, connected TV OS, subscription marketplace and, if not its own proprietary SVOD, at least a high-profile partnership to offer one. Though e-commerce has steadily eaten away at the traditional retail business, Walmart is one giant that can’t be slayed so easily.

A slightly tangential example is Bytedance (parent company of TikTok) launching Melolo in Google Play Store, which is a free short form drama app targeted at Southeast Asian audiences, featuring romance, thriller, and costume genres around 10 - 20 minutes long.

Of course, companies like Netflix have been investing in games on their platform to encourage users to spend more time with them for all their entertainment needs, not just streaming TV and film. Streaming service Peacock announced this week at CES they are experimenting with mini-games and short videos.

While there may be some tactical activity here to try to grab audiences in advance of a potential US ban of TikTok (plus of course, many companies would love to emulate the success the New York Times has had with its games and cooking strategies), it will be worth watching how a broad range of companies - some from outside the media space - are competing to power consumers’ lives.

Brands as competitors, commissioners and funders

Building on the section above, this year is likely to see more activity around brands either as funders (or part funders) of TV shows that previously would have been fully financed by traditional TV commissioning and distribution models.

How do producers further develop their understanding of how brands view a TV show? After all, for a brand, the TV output often isn’t the end point of the user experience, rather it is just one element within a complex network of activities that have a clear set of objectives to achieve.

We’ll also see some further development of brands as media companies. For example, assuming the Walmart deal to purchase Vizio mentioned above gets regulatory approval, what does that mean for the streaming market both in terms of originals and acquisitions, as well as how will Amazon and others respond?

Other brands are likely to further push into the space of commissioning originals for their own channels as well as to distribute to broadcasters and streamers.

How do producers go about courting brands and position their projects to align with brand expectations, knowing that brands may have longer lead times and key objectives that need to be aligned with?

Innovative funding models for TV and film

Last year, there were several interesting case studies whereby creatives found new ways to self finance their TV and film projects. Firstly Mark Duplass’ series Penelope and secondly, Glitch Productions’ series The Amazing Digital Circus.

This year is likely to see even more projects with interesting financing, IP and recoupment models, and is definitely a space to keep an eye on.

AI - copyright and adoption

If you aren’t subscribed already,

’s is a great place to understand the wider implications around AI for those in the IP owning and content creation business. If you are interested in a free subscription, drop me a line at hello@businessoftv.com.Meanwhile, C21 have done a great write up of the AI panel at Content London:

In a hugely simplistic nutshell, the AI challenge comes in two forms - inputs and outputs.

In terms of inputs: what are the rules around AI companies training their models on existing IP? Do they have free rein to train their models on any content they want on the internet, without needing specific permission or paying compensation to the IP owners? Or do they need to get permission (and agree deal terms) with individual IP owners? In practice, do IP owners (from an individual artist all the way up to the BBC) have to contact all AI companies to say they don’t have permission to use their material to train their models, or does each AI company have to contact rights holders to seek permission?

And for outputs, this is around how AI is used within the production processes of TV, film and digital content, and how streamers, commissioners, brands, broadcasters and financiers walk the tightrope of creativity while managing the human cost of this technology. Simultaneously, these tools are available to any human in the world, which will therefore see an explosion in content being produced that may come to rival the content being produced via the traditional TV, film and digital content sector. Will we drown in this content and seek refuge in quality human storytelling brands and curators? Or will the democratisation of content production simply breakdown the old citadel of TV and film production, as suggested in the Content London panel written up linked to above?

In the next weeks, the UK government will have to decide whether to have an opt in or opt out model for the copyrighted material that AI tech companies want to use to train their generative AI models on. At the moment, the UK government appears to be leaning towards allowing AI companies to use copyrighted material without having to seek permission, and therefore the onus will be on individual IP owners to opt out of these models.

Managing AI content, and dealing with AI slop

If you haven’t yet started tripping over generative AI content on your social feeds, then it is likely you will soon. These can come in the form of images, video, AI chatbots and more, and the volume, veracity and ethics around this content is going to be a big trend over the coming year and beyond.

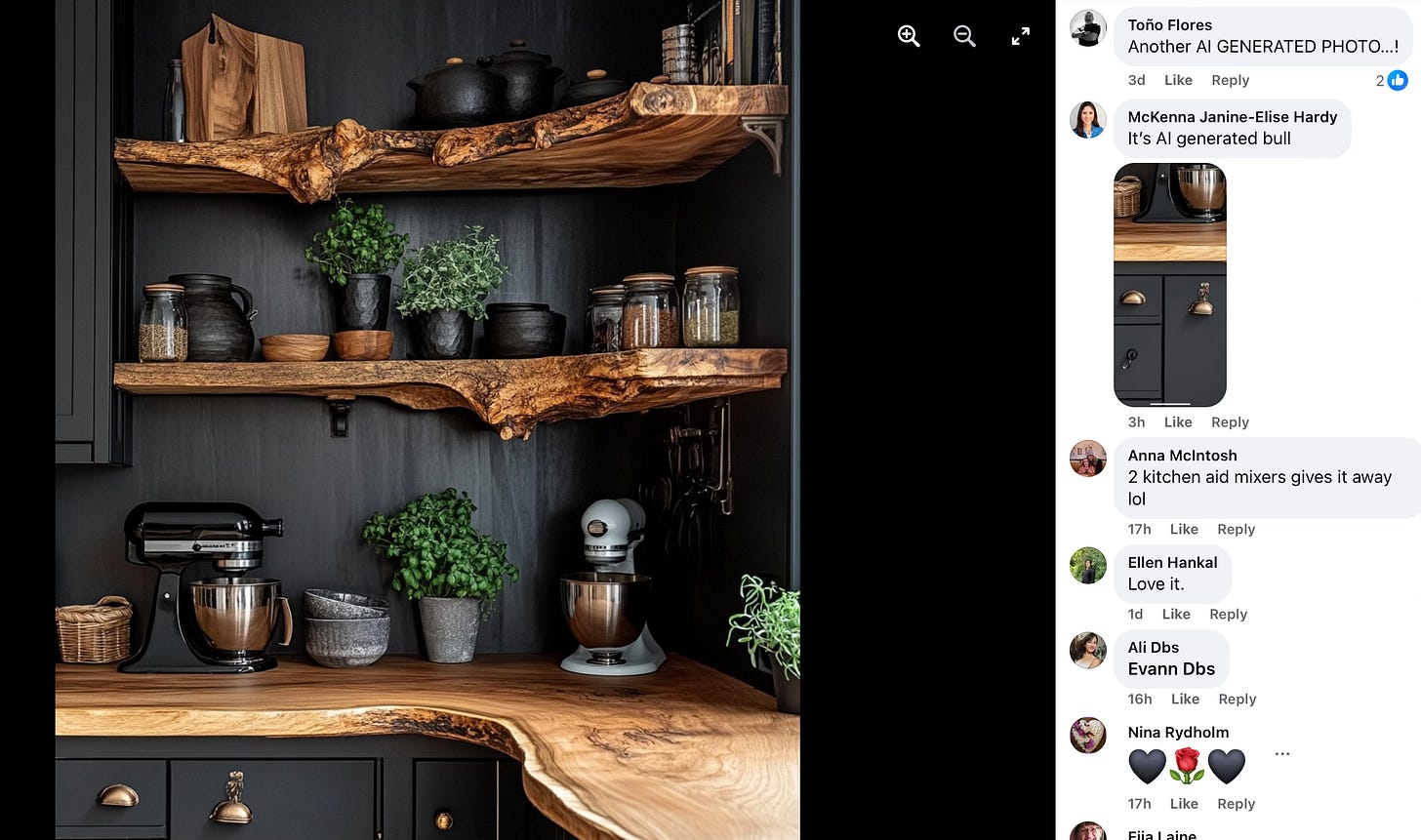

As an example, homes and interiors is a common genre where AI imagery is starting to appear regularly especially on visual platforms like Pinterest, Instagram and Facebook. The image below is from a Facebook page with over 500k followers, and from the comments you can see the challenge as some users don’t care the image is AI as they are seeking inspiration, while for others its lack of authenticity is a turnoff.

On YouTube, there is a growing number of AI generated faceless channels. Some of these are of quality however there is also a get rich quick trend where people attempt to use AI to generate videos to hit the monetising threshold on YouTube so they can make some income before YouTube then in all likelihood kills the channel.

If you are interested in understanding this trend and get under the hood of why it is increasingly a problem, then below is a hugely entertaining hour-long explainer:

The growth of AI content and AI slop will be significant in a couple of ways over the coming year. Firstly, what will be the strategies each social and video platform adopts to deal with this type of content. Will they continue the current whac-a-mole approach, or instigate some sort of platform wide crackdown? Will they block monetisation to disincentivise individuals from making this type of AI slop? Or will some sort of flagging system be developed to alert users to AI material? What about the volume of disinformation in some of this content? How are users to know which is accurate or harmless AI generated material and which is misleading and false? Will there be a backlash from advertisers who don’t want to appear next to this type of material?

Secondly, will there be a similar audience backlash against this type of AI material, and will it result in a desire for greater human authenticity, connection and reality? As anyone in TV knows, it is normal to have swings against whatever has been a dominant trend for a period: after lots of constructed reality shows comes a desire for observational programming; or a period of uber violent crime thrillers is often followed by a desire for quieter and perhaps more sentimental murder mysteries and so on. Is it fair to assume we may see a similar swing to normality once our online world is full of AI generated material?

What opportunities and challenges this presents to TV and content producers is something to think about.

Growth in ad-funded streaming models

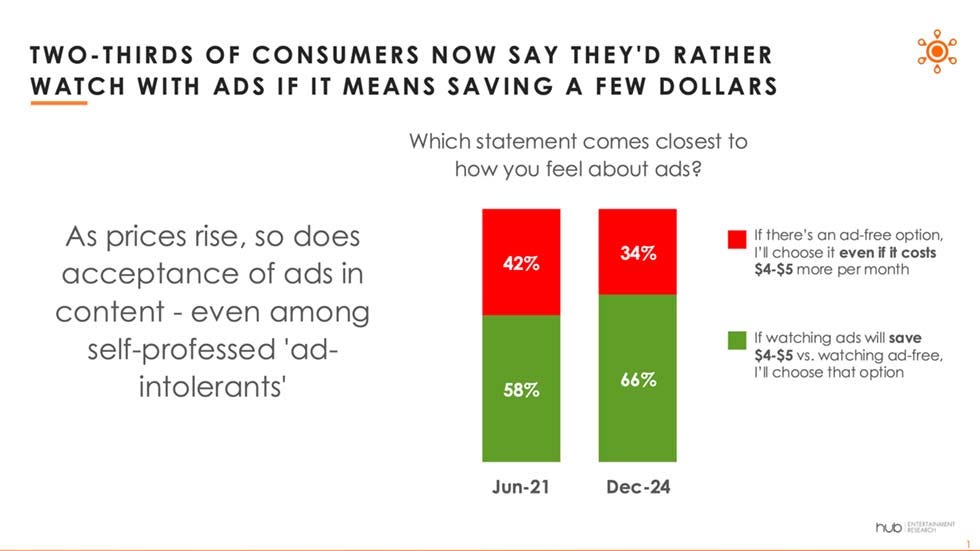

The rise in ad-funded viewing is likely to continue and mature well into 2025. The Hub’s annual survey that tracks opinions on advertising shows that users are increasingly tolerant of advertising over subscription costs:

Over the last year this has been good news for UK PSB broadcaster and advertising VOD services which saw BBC iPlayer, ITVX and Channel 4 reported positive viewing numbers. And as Ampere Analysis notes, the UK streaming advertising market is now valued at over £1bn as platforms like Amazon and Netflix have launched ad tiers in the last year: “The streaming advertising market in the UK is now one third as big as the traditional TV advertising market.”

However, as more ad-funded streaming platforms emerge - Amazon, smaller players like Tubi and obviously YouTube - and the amount of advertising capacity increases, what is the impact on ad revenues for each individual service, platform or FAST channel? As the above Guardian piece notes:

“The likes of Netflix may only be taking some crumbs off the table of an ITV or Channel 4 at the moment,” says the media analyst Alex DeGroote. “But sooner or later these ad tiers are going to really work, and then – watch out.”

And specifically, as broadcast viewing declines - and so far the revenues from streaming isn’t making-up the difference - how will UK broadcasters deal with the growing competition for share of the ad market from an increasing number of other players?

Global niches and the need for curators

Being able to reach a global audience via the Internet means that niches that would be too small in a single territory suddenly become meaningful when there is access to the whole world.

Identifying and serving global niches of all flavours has been a key factor in succeeding online irrespective whether a single creator all the way to large corporations. And as traditional TV and media continue to be disrupted by technology and the internet, then for TV producers it will increasingly be important to understand how they can tap into a global niche (or niches).

I’ve written before about how producers can build direct relationships with specific audiences:

Examples include businesses like Mubi (arthouse cinema) or Cineverse (horror) to reading clubs (Reese Witherspoon) or shoe retailers (Foot Asylum).

As for YouTube creators, niches are where many have had their success - below is a post with numerous examples of successful niche channels to explore:

Over the coming year, it will be interesting to watch where new niches emerge from - both individuals and companies - and what new insight can be gained from each one.

To pick an example, Jolt.film (from the same team that previously launched Impact Partners) is a pay per view streamer of a small curation of independent films. It currently has two Oscar shortlisted feature documentaries on its platform - The Bibi Files and Hollywoodgate (although neither are available to watch in the UK). This Variety article explores how Jolt.film aims to be a solution to feature documentary distribution issues.

Another example is anime. At CES this week, Sony announced further investment in its anime brands including Crunchyroll as part of its evolution from being purely a device manufacturer and into being a global content empire.

The close cousin of niches is the desire for curation. The upending of traditional media has meant that in a bubbling sea of content, products and services as well as increasing automation, people are seeking trusted individuals and brands to identify what they might be interested in. Curation comes in many shapes and sizes, from broad taste makers to subject specialists, however the desire for curation beyond what is automatically generated seems both a trend and an opportunity.

Continuing to rediscover what works

In the great upending TV and film has gone through in the past years, some argue that known truths were jettisoned in the process, and in the last year these truths are being rediscovered by a broad range of players from networks to streamers, individual creators to brands.

is one of those beating the drum that genres which have long worked on TV have worked for a reason. As he said recently, the following genres are under-rated because of “apocalyptic headlines or the streamer’s lack of interest in them”:Sitcoms/Comedies that are actually funny. Even though its ratings dipped later in the season, the Night Court reboot was the breakout hit of the year. Meanwhile, as Elaine Low reported in the Ankler, people in town want funny comedies now. I couldn’t agree more.

Procedurals. Thanks Suits! Now everyone realizes (again?) that many, many viewers like procedural dramas.

So is 2025 the year we see a return to more sitcoms and procedurals, as well as other less prestige, more predictable and longer running series like soaps, cheaper game and quiz shows and fact ent lifestyle titles?

That's a pretty long list… I could have added in more, from kids safety online to the rise in production companies as consumer brands, but needed to stop somewhere! And as often is the case, it is the thing you aren’t looking for that becomes significant.

Let me know what you think in the comments below, follow @businessoftv on X or on BlueSky, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Typo "Paramount’s streaming service Peacock announced this week at CES"