Why is tech spending big on content plus Netflix's ad push & YouTube taking the top distributor spot for the first time

As tech companies such as Apple scrutinise their originals spend, how does content fit into their overall ambitions?

Hello! This week, I’ve covered three (different) trends that popped up in the last couple of weeks:

Amid general nervousness around the future of tech investment in content, how does spending on originals fit in with each company’s wider strategy?

US quarterly viewing figures are out and YouTube has taken the top distributor spot for the first time. In lieu of any announcements, commentators are reading the tea leaves on what next for Warner Bros. Discovery.

Free ad-supported TV services continue to grow in the US, but the leap to advertising models is tricky for those new to the market.

Tech companies and content: Is the real battle to power our lives?

How the billions spent on original content by tech giants fits in with ambitions to be the software company of choice for all our devices and services, not just streaming video.

There has been quite a lot of noise in the last few weeks about Apple’s content strategy. Apple TV+ had just 0.3% of total share TV screen usage in June according to Nielsen, however for originals, it is third amongst the eight major streaming services in US audience demand for originals according to Parrot Analytics. This suggests shows such as ‘Slow Horses’ are hits with audiences, despite the overall offering including acquisitions and archive having struggled to establish a large regular active user base.

As for Apple’s film investment, eyebrows have been raised at the pivoting to a limited cinematic release of ‘Wolfs’ (starring Brad Pitt & George Clooney). This follows a series of award-winning films that cost a bomb but haven’t (or could never at the price) deliver box office profits. As an example, ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ is rumoured to have cost $200m, and therefore would have needed to do something north of $500m to generate a profit. It did $157m in ticket sales (although obviously this doesn’t taken into account its success on VOD services).

For some commentators, they are worried that if certain tech companies start to question the rationale for continued investment in their TV and film operations, then the pain felt by our industry will be seismic. As Richard Rushfield warns (although worth saying he does call himself a catastrophiser):

The problem for us all is that in lieu of a plan to grow the entertainment audience, we’ve been riding high on the easy money these tech companies have been throwing around. Contemplate the festival world for instance, minus the streamers. Or consider the TV business, already in enough pain, if a couple tech conglomerates decided they didn’t feel like doing this anymore. In all likelihood, they are in too deep and too publicly to just stop, but certainly they could decide to, say, cut their spending in half. Or by 70 percent. You think there’s pain in this business now? Just try that on for size.

It isn’t like we haven’t seen tech companies pivot away from originals before when it became clear that content wasn’t helping drive the company’s overall strategy (although some had previously pivoted back to originals after an earlier pivot. There’s a lot of pivoting in Silicon Valley). Both Snapchat and YouTube Red shut their originals teams in 2022, and Facebook Watch did the same in 2023. Back in 2014 Microsoft exited the streaming TV business after a short foray when it shut Xbox Entertainment Studios (disclaimer, I worked at Microsoft as part of their push into TV at the time).

As all organisations including Apple, are looking closely at their content spend and return on investment, perhaps it is worth viewing the tech companies originals activity in the wider context of their overall business strategy. For these companies, it isn’t so much about winning the streaming wars and creating profitable video services, rather the bigger war is to own the whole media experience for users across the globe.

We can see indications of this as certain companies are increasingly focussed on time spent as an important metric. So rather than (just) saying “we are a broadcaster or a streaming platform, let’s offer better or more interesting shows”, perhaps companies are now asking “what is it that people want to do in their spare time, let’s offer that”. And thus, Netflix invests in games as a result, and shifted their North Star metric from subscribers to time spent.

For some companies, it isn’t just about the hours spent watching or consuming TV, films or games. Rather, the ambition is to be the operating system of choice that underpins people’s lives. This is about all aspects of our day-to-day activities and the tools we use such as productivity software, account management, calendars, banking, shopping, chat, entertainment services and more; across all our devices such as phones, laptops and TVs but increasingly cars, domestic appliances, audio, home security. Where our fridge knows we are out of yoghurt and automatically adds it to our shopping basket.

This is why LG announced last year a $756m investment in its webOS operating system to become a ‘media and entertainment platform’, so people will use webOS on their TVs and in time, on their phones, fridges and washing machines. Crucially for producers and rights owners, LG are actively acquiring TV and film titles for their premium, free streaming service LG Channels 3.0, which has 50m+ subscribers in 27 countries.

From this aspect, the enormous content spends for relatively small slices of the pie by the likes of Apple TV+ can make sense. In other words, content acquisition and commissioning is seen as an attractive and monetisable (with a question mark over profitable) product that enhances their overall software/hardware and services business.

It’s important to note that Apple’s hefty investment on original media content is not just about trying to win the streaming wars… The real battles are between the operating systems and the aggregators that control the entire media experience. By that measure, Apple is well-positioned to lead the game … which is rooted in tech and iteration, something it does better than virtually everyone. Controlling the media experience allows for greater collection and control of user data, advertising and subscription revenue shares, as well as promotional power on valuable homepage real estate.

Looked at in this way, you can see that Apple, Google, Facebook - plus others - are seeking to be the operating system for everyone, and content is just one way to encourage this reliance. Whether originals spend continues to fulfil this role for these companies is the question that will remain over the coming period.

US cable TV continues its trajectory

US quarterly viewing figures are out and YouTube has taken the top distributor spot for the first time, relegating Disney to second place. Plus in exploring what assets WBD could sell, it becomes even more apparent how challenging any decision making must be.

The July data from Nielsen’s The Gauge shows for the first time a streaming platform breaking 10% audience share (YouTube excluding YouTubeTV), driven in part by school kids on holiday.

Perhaps more significantly, July saw YouTube take the top spot for the first time in terms of media company’s share of total TV usage, overtaking Disney.

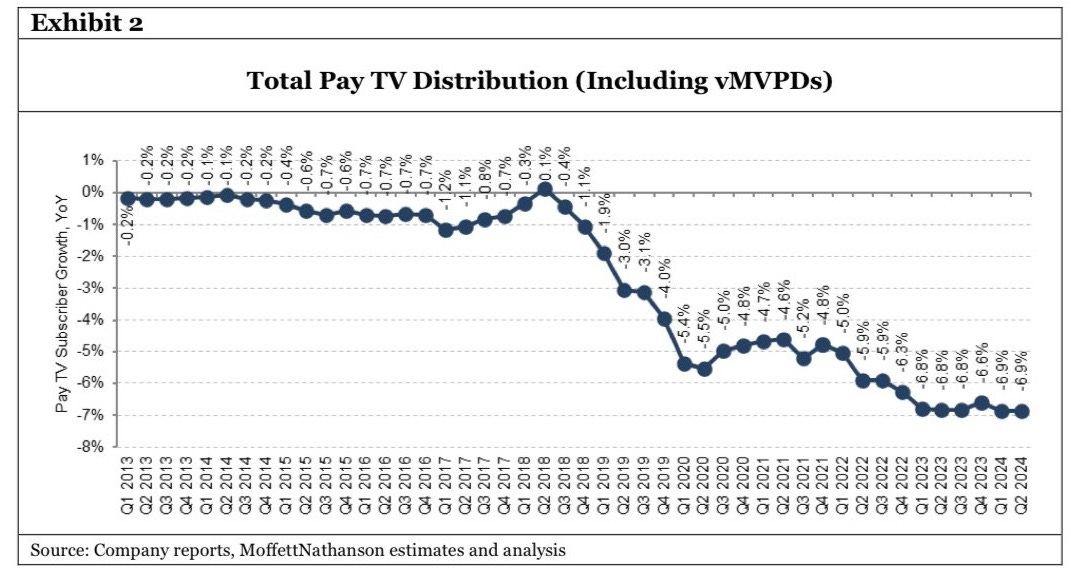

And Q2 2024 pay subscriber numbers make for (continued) grim reading - down another 1.6m subs (-6.9%). Analysts MoffettNathanson stated: “It is becoming increasingly clear that there is no longer any floor” for total pay subscribers in the US, where previously the general view was the floor would be around 50m subs.

In recent weeks, commentators have been playing guessing games on Warner Bros. Discovery’s next moves. As there hasn’t been much action on this front, Puck did a quick run down of the options for a firesale of assets, and made a punt at the appeal and likelihood of each one. As a reminder why it is believed *something* will happen (but no idea what), Puck put it like this:

The recent quarter’s financials were scary—scary even for Hollywood in 2024—with that $9 billion write-down of the television assets, revenue declining 6.2 percent across all its units, and the “irreparable harm” the company says is coming from losing its most important TV franchise: the NBA. With subscribers and advertisers permanently abandoning linear TV, and a credit downgrade by S&P Global from “stable” to “negative,” there are few signs of light at the end of this two-and-a-half-year Warner Discovery tunnel.

The non-core assets that could be sold (according to Puck anyway) include CNN, the Food Network & HGTV (perhaps to Walmart?), European TV channels, the games division, Looney Tunes, New Line Cinema. The piece is a slightly lighthearted paper exercise, however what is clear is that there are no easy solutions. Each asset listed has some pros and often a lot of cons for selling. For example, both CNN and the Food Network & HGTV are important news/lifestyle brands in the portfolio that make up WBD’s carriage and advertiser deals.

Separately, there has also been an ongoing battle between DirecTV and Disney over its carriage deal, which has seen Disney channels removed from 11m subscribers on Sunday. These types of skirmishes are not uncommon in the US market when deals come up for renewal, however commentators believe this one has strategic significance in the great TV unbundling that is undermining the traditional US TV carriage distribution model. The Wrap said:

Instead of preserving bundles that might leave viewers with offerings they won’t use, DirecTV is pushing for channel packages to be “whittled down” from mega bundles to genre-based offerings tailored to customers’ viewing habits.

We’ll have to wait and see which company blinks first or whether the two can come to some sort of compromise.

Free TV services continue to grow

Free ad-supported streaming is growing in the US, creating more opportunities for producers, however possibly not at the budgets paid by subscriber platforms.

Business Insider has a piece this week on the rise of free TV in the US, and how that is creating yet more competition and pressure on the hunt for profitability for streaming services.

It is important to note that this free versus paid dilemma could be specific to the US market, compared with the UK where free streaming services have been the norm for over 18 years - I wrote about this in greater detail when free streamer Tubi launched in the UK. However, because of the global nature of streaming, US market conditions affect UK producers whether or not they directly work for US-based networks.

The Business Insider piece isn’t exactly all sunshine and flowers on the future of the TV industry:

The big fear in Hollywood is that Peak TV is gone for good, and the entertainment giants are doomed to fight over an ever-smaller slice of attention. The industry won't go extinct. Netflix is doing fine, after all, and Disney is a behemoth.

But occupying a diminished state in the entertainment landscape isn't exactly glamorous. Just ask the magazine industry.

The central concern is that free ad-supported streaming TV doesn’t generate the revenues required to support high end originals when compared with Netflix et al’s budgets. As the Business Insider piece outlines:

Roku's annual content spending was pegged at "more than $1 billion" in 2022 by CNBC, a far cry from the $17 billion Netflix plans to spend this year; Roku's most ambitious film to date, a Weird Al biopic, cost only a reported $12 million to make (Netflix routinely spends over $100 million for a single movie). Tubi's net investment (which content is a part of) in the fiscal year 2024 was in the mid-$200-million range.

Having said that, TV has always had a range of price points and tariffs, and when some of the larger streamer budgets are believed to be international buyouts of residuals rather than actual production costs, perhaps this will see even more of a return to territory by territory deals for individual titles.

Also in the last few weeks there have been insights into Netflix’s advertising push, following the company’s announcement that it increased its ad commitments in its upfront negotiations by 150% compared to last year.

Netflix’s ad strategy was always going to be more of a challenge than Amazon’s. As outlined by Michael Nathanson earlier this year, Amazon flipped all 200m subscribers onto the new ad tier automatically, while Netflix’s allowed people to opt in, of which around 40m have done so thus far. This made it hard for Netflix to maintain its high CPMs (cost per mille, or cost per thousand which is the unit price for advertising) for this relatively smaller audience, and as a result they cut their prices - although not as low as Amazon’s. Digiday have a piece on Netflix’s progress in their ambition to woo advertisers, and it is worth reading for a lot more detail on the challenges and the company’s progress.

Evan Shapiro has written a hugely entertaining (as always) Substack on the obfuscation game played by all the streamers when it comes to declaring profits, and called out Netflix’s recent ad announcement specifically:

Netflix has been hiding the weenie on their ad business since its launch. We have no idea how many subscribers they have on their ad tier, because their data is always just as convoluted as “150% of something.” But I’ve seen reliable data – coming to you very soon – showing that Netflix’s advertising platform garners less viewership than Tubi, Pluto, Peacock, Paramount+, and Prime – as well as Investigation Discovery, AMC, and Hallmark Mystery Channel. Netflix’s ad tier has 9X fewer viewers than MeTV.

Evan excels at top class graphics, such as this one below - which he describes as “for those who aren’t good at math let me do it for you”:

Other bits and pieces:

The Times (£) has a fun read on the goings on within the James Bond franchise after Amazon paid $8.5bn for MGM in 2021

The Streaming Lab: An interesting overview of the Indian streaming market, especially for reality TV and audience interactivity.

Follow @businessoftv on Twitter/X or say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com.