Is AI experiencing the trough of disillusionment?

From concerns AI's got cognitive dementia, to worries about its psychological impact, AI appears to be going through a tricky phase.

Despite having spent all my career at the edge between tech and TV, as yet I haven’t written a huge amount about AI. This is partially because there are many others deeply immersed in the industry who are doing a great job of tracking its development, but also, more significantly, because the specific nature of the hype around AI makes it exceptionally difficult for non-technologists to sort out the signal from the noise.

So at this stage of its evolution, I haven’t thought it is helpful to give you regular updates of the latest goings on in the world of AI that may - in the longer run - turn out to be a diversion, wrong or simply a waste of your time. In other words, I don’t want to send you barking up the wrong tree.

Despite these reservations, there has been much activity and movement in this space over the last few months, and while we wait to see how it evolves, there are a few significant themes and concerns that I thought you should be aware of.

A quick explainer

Before getting going, I thought to add a little further explanatory note: AI is not one thing, indeed there are multiple types all at various stages of development.

You’ll have heard of Generative AI, where a user prompts the system to produces outputs - code, video, text, images, audio and so on - which are generated based on inputs the system has been trained on (it is both these inputs and outputs which are the focal point of the ongoing fierce copyright battle).

Conversely, Agentic AI is like a proactive assistant designed to take actions without humans constantly directing it, and also it is intended to learn from outcomes and make decisions based on new information.

Both of these types exist in various forms right now, and are often referred to as ‘narrow AI’, as this IBM explainer says they:

… excel at sifting through massive data sets to identify patterns, apply automation to workflows and generate human-quality text. However, these systems lack genuine understanding and can’t adapt to situations outside their training.

What technologists, scientists and engineers are hunting is what is called ‘strong AI’, such as Artificial General Intelligence - where they are as smart as us; or going even further, Artificial Superintelligence - where they are smarter than us.

In this quest for both narrow and strong AI solutions, billions of dollars have been invested so far in research and development. To illustrate some of the cash involved, here is a graph from this week’s The Information Creator Economy newsletter by Kaya Yurieff which shows US funding for creator startups - so this excludes spending within non-startup companies and also any investment outside the US:

There are a wide range of examples where AI is already transforming the world of work - including TV and film production - never mind the advances in specific areas such as the analysis of complex datasets in the science and medical fields.

However, in this post, I’m focussing on some of the sticky issues AI is running into, and especially how this relates to human creativity and psychology.

The backlash against AI hype

You might be familiar with Gartner’s hype cycle, which is a useful concept to understand how new technologies appear which can often lead to mass hysteria, only to be flooded by disappointment. Sometimes these technologies disappear, in other instances people eventually find a place and role for them, so they become normalised.

What is notable is that often, the time it takes for a technology to hit point 4 and 5 in the hype cycle is much longer than the early excitement predicted - so by the time it comes around, there can be a level of world weariness and perhaps cynicism about the technology, even as it becomes part of the mainstream.

Thinking back even over the last few years, and you can probably identify several technologies that fit into this model which have yet to become normalised (assuming they ever will): NFTs, wearables, the metaverse. Indeed, for those who have been in TV for a long time, you’ve probably heard your digital colleagues hyping the internet as a potential TV disruptor since the early 2000s. It could be argued it has taken around 20 years for that hype to become a reality in our industry - and even then, many of the nirvana-like features have yet to become common user behaviour. For example, ‘you’ll be able to buy what a character is wearing at a click of a button during a show!’. Well yes you can now do that on certain platforms watching certain shows, but thus far it has not become anything like the mainstream activity many imagined.

Right now, some are wondering if AI is on the downward slide towards the trough of disillusionment, thanks to a whole range of factors. This Wired article summarises many of the issues, outlining an overall growing animosity towards the technology:

…the potential threat of bosses attempting to replace human workers with AI agents is just one of many compounding reasons people are critical of generative AI. Add that to the error-ridden outputs, the environmental damage, the potential mental health impacts for users, and the concerns about copyright violations when AI tools are trained on existing works.

And so, I thought I’d do a post digging further into some of these issues (as well as a few more)…

Copyright concerns get louder

The breadth of individuals, companies, publishers, artists and organisations that have concerns - if not full-on rage - at the lack of control over their creations is getting more vocal. I’m not documenting the range of frustrations here, instead they can be succinctly summarised by author and The Rest Is History host Tom Holland’s response to a user saying ChatGPT was quoting from his work:

That’s because the bastards have strip-mined my books.

To give a practical example. Here is a recent situation that demonstrates the idea of copyright opt outs rather than opt ins for AI large language model (LLM) training is unworkable in reality. Music producer and YouTuber Curtiss King shared this video of artist KFresh’s track, and then a clip of Timbaland sharing a track that was produced by Suno (the AI company where Timbaland is creative director):

This caused somewhat of an online storm, and KFresh went on to do the following interview with Curtiss King:

Timbaland subsequently issued the following statement:

The reason for drawing this to your attention is because it shows how theory can fall apart in practice; the theory being it plausible and reasonable to expect artists to opt out of their works being used to train LLMs. But in reality, KFresh didn’t know his work was being used in this way until Curtiss King spotted it. As Ed Newton-Rex, composer and CEO of Fairly Trained noted:

Even if Suno gave you a way to opt-out of training - which they don’t - there’s no reason KFresh would have heard of it. KFresh has zero control over Suno training on his music. This is why training must be based on opt-in licensing. Anything else exploits musicians and their work. Opt-outs don’t work.

And there are other instances where you can see this unhappiness from creatives about their works being used for AI training without permission or compensation. As Ezra Cooperstein, president of Night said while sharing a CNBC article about Google using YouTube’s libraries to train its AI tools such as Veo 3 and Gemini without permission:

Time for YouTube to be honest with creators. I have no doubt the platform has disregarded their own terms of service and also failed to enforce other foundational labs doing the same.

The CNBC article included Google’s response:

Google confirmed to CNBC that it relies on its vault of YouTube videos to train its AI models, but the company said it only uses a subset of its videos for the training and that it honors specific agreements with creators and media companies.

There is a still a long way to go in this copyright tussle. And in the meantime, the same as in any hotly debated area, opportunities emerge. Cloudflare, the hosting platform, this week introduced a service to block all AI crawlers from trawling any website hosted on their platform, unless the AI company pays a fee. While this doesn’t protect content beyond their infrastructure, they’ve clearly spotted the potential upside of protecting the copyright of their clients. This is one of many shifts in the market where you can see players spying a way to grab an advantage. It will be interesting to see what other competitors or website building platforms do in response.

Concerns about the psychological impact on humans

Serena Williams’ husband, Alexis Ohanian (founder of Reddit) posted a video online where AI had been used to animate a photo of him and his mum who passed away a long time ago. He had a very human response to seeing her brought to life in this way.

However it prompted much discussion (which is worth reading) that was split into two camps: those that thought AI offered a lovely way to bring loved ones back to life, and those that were horrified by the potential psychological dangers this posed to how humans deal with grief and loss. For example, one user wrote in response:

Cognitive security Rule 1: Do not do this.

Or to put it another way, if as a species we’ve struggled to cope with the negative effects of social media, how will we deal with gen AI putting us in a psychic state where we are creating false memories that might block us being able to process death? We can expect to hear a lot more about this issue over the coming months and years.

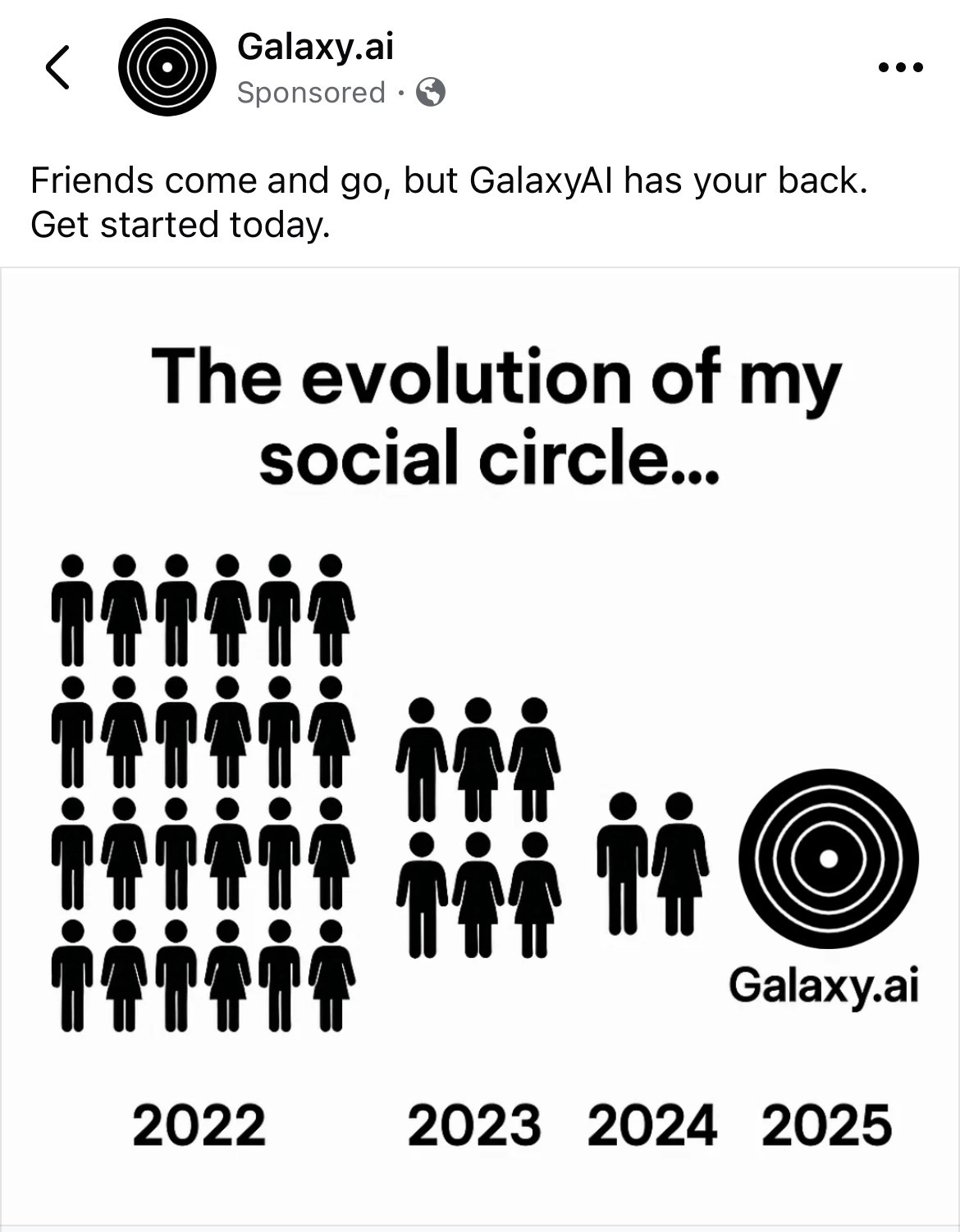

Meanwhile, this appears to be a real advert by Samsung’s AI companion Galaxy. Thanks to

for sharing.Not as clever as first thought

I’ve shared previously that there have been various research papers showing that LLMs aren’t as clever as it has been suggested thanks to it having problems with reasoning.

Some are going further by saying LLMs have fundamental limitations, which may mean that to achieve the potential of what has been dreamed of (which is artificial super intelligence) could involve a major rethink.

For example, Kings College London back in April suggested a new test for artificial superintelligence, and quoted Gary Marcus, Professor of Psychology and Neural Science (Emeritus), NYU, and Founder and Executive Chairman of Robust AI:

This study fits with what I’ve been arguing for years—Large Language Models, despite their hype, are not moving towards real intelligence; they continue to struggle with abstraction, reasoning, and planning. These results suggests that LLMs are not converging to anything resembling general intelligence, but instead remain brittle, erratic, and deeply dependent on the specific data they memorise —suggesting we need a new approach.

Recently there was this interview with one of the greatest living mathematicians, Terrence Tao (self indulgent side bar: we went to the same high school, although he finished just as I started - despite him only being a year older than me!). He talks about AI currently not passing what he calls the mathematical smell test, and that it struggles to know where it has made a wrong turn. In other words, what it considers to be correct isn’t actually correct (starting at 1:48).

So are LLMs a route to AI super intelligence, or are they a dead end and instead scientists need to go back to square one to figure ASI one out? For non-technologists, it is very challenging - if not impossible - to be able to comprehend all these various scientific arguments. Indeed, even those working in this area disagree with each other.

This isn’t that unusual; after all, since the 1980s the tech industry even has had a word - vaporware - for software, products or services that don’t quite materialise as originally hoped for a whole range of reasons.

There was another story this week, as Meta has hired a new ‘AI superintellligence super-group’ with eye watering sums paid to these new employees, many of whom were previously working for Meta’s rivals.

For many, this move is further evidence of the high stakes involved as big tech invests in AI. For others, it has prompted some further pondering whether this could actually signal a change of direction in the hunt for artificial superintelligence in new areas away from LLMs. One to keep an eye out for as it unfolds.

Meanwhile, another story came out in the last few weeks relating to how big tech is approaching AI: Apple is reportedly considering either using a third party AI provider such as OpenAI or Anthropic, or indeed buying a company like Perplexity.

Bloomberg: Apple Weighs Using Anthropic or OpenAI to Power Siri in Major Reversal

Tech Funding News: Apple eyes $14B Perplexity AI deal to break free from Google’s grip

Bloomberg: Apple Has No Need to Panic-Buy Its Way to AI Glory

As with all of these types of rumours, it prompted a flurry of opinions. For some, relying on a third party’s AI is troublesome for Apple, as it might mean they don’t have their own foundational AI system. For example, the suggestion was described as ‘absolutely astonishing’ and a ‘metaphysical betrayal of their own DNA’ because the company:

…used to own the full stack, silicon to software to services. Now they’re outsourcing the one layer that will define the next decade of computing.

For others, they think a purchase of something like Perplexity is a smart move, as

wrote:Apple buying Perplexity is such an obviously good deal for both companies that I feel silly even writing it down. Apple would get a bonafide AI service it could plug right into Safari and Siri that would revamp its disappointing AI offering. Perplexity would get access to the 2 billion+ Apple devices in circulation and become an AI force on par with ChatGPT.

Here is a clip from LightShed Partners’ podcast, where Rich Greenfield suggests Apple should buy Perplexity over HBO.

While all of this may feel a bit peripheral to TV producers at the moment, whatever happens with the direction for both big tech, LLMs and so on is likely to have some sort of an effect on TV production - what that will be is hard to judge, but none of us exist in isolation in this converged world.

AI starts eating itself, compounding errors

One of the issues with AI that I’ve long wondered about is: what happens to truth and data integrity when errors get fed into the system? And what happens when/if there is a reduced volume of new authentic human-produced material for it to be trained on (ignoring copyright for the moment)? In other words, does AI start to reference itself as proof of truth, so does it start eating its own tail? How can humans identify this is happening, never mind how do they intervene? Especially, if as Terrence Tao said, AI doesn’t have the capability to work out when it is wrong?

HuffPost published an article this week on this very issue, which said ‘Amid claims of "digital dementia," experts explain that AI isn't declining. It's just stupid in the first place.’

The article says that AI is already suffering cognitive decline because it is running out of good data to train on. In addition, the study the piece references says that 25% of new content on the internet is AI generated. It goes on to ask:

…if the content available is increasingly produced by AI and is sucked back into the AI for further outputs without checks on accuracy, it becomes an infinite source of bad data continually being reborn into the web.

At this point, I refer you back to the Disinformation Summit held a few months ago, where Alan Jagolinzer, Vice Dean of Programmes at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School said the root of disinformation is international crime syndicates and mafia states taking over nations and running manipulative campaigns via platforms that are not rigorously moderated enough by tech companies. And then cowardice amongst us all for not intervening. He said:

[We have] a transnational organised crime syndicate (or mafia state) problem, many of which have taken over nation states and are colluding to leverage manipulative influence campaigns and crypto financing to undermine democratic and accountability institutions globally. I sense they have an insatiable appetite for raw dominance power and that there are very few months remaining before they usurp our collective power and influence, given their heightened aggressiveness, without serious intervention.

Well, when you put AI eating itself and further embedding bad information as truth into that mix, and that it can’t recognise when it’s wrong, does it make you pause for a long moment? Alan Jagolinzer’s full analysis of the shape and nature of disinformation is below, and I’d urge you to read it:

To give more reasons to pause for thought, here is Signal’s president Meredith Whittaker at SXSW, explaining why the concept of agentic AI - where as she says we put our brains in a jar and the agent can do everything for us - can cause major security and privacy breaches. Or as she describes it, we are breaking a technical blood brain barrier to be able to get these agents to work, which therefore can have profound impact our privacy (starts at 50:15):

How long will the gold rush AI slop last

Moving on from these thorny issues, to the consequence of gen AI on the content world. The arrival of these video tools has unleashed a whole volume of content onto all the various video and social platforms, partly where users are enjoying the creative process, but also because it is perceived as a quick route to making money (despite running the risk of having your account de-monetised or shut down by YouTube in response).

As a single example of the many out there; right now there is a trend of AI generated videos featuring foods that look like glass being sliced. These have often been produced by Veo 3, Google’s AI video product, and these videos are generating income for their creators on YouTube. For example:

In turn, other users create (and monetise) videos to show how you too can make similar videos. So the channel owners are monetising their ‘how to’ videos, as well as their training packages for mastering ChatGPT or various video AI tools. As Veo 3 costs money, they often create more videos showing how you can make glass cutting videos using free AI video tools, rather than pay the Veo 3 fee. An example is below, but there tonnes of these on YouTube and TikTok:

Often these are marketed across social as ‘look at all these channels blowing up on YouTube and TikTok, you can too’ or ‘here’s the quickest way to make $50,000’.

This creates a tricky dance for platforms, as on the one hand they want people to use (and pay for) their AI products to create content that people watch so they can sell more advertising, but on the other advertisers often don’t want to appear around this low quality content and there is a risk of driving away audiences who get tired of the volume of AI generated material. Plus, there are legal risks in some of the material produced - for example:

We can see a little indication this week in how YouTube is trying to straddle these two horses, with the announcement that their monetisation policies are being updated to target inauthentic mass-produced and repetitive videos. While at the same time, they are also plugging Veo 3 directly into Shorts.

YouTube’s recent statement on the changes to its monetisation policies is below:

In order to monetize as part of the YouTube Partner Program (YPP), YouTube has always required creators to upload “original” and "authentic" content. On July 15, 2025, YouTube is updating our guidelines to better identify mass-produced and repetitious content. This update better reflects what “inauthentic” content looks like today.

We’ll have to wait until July 15th to get a better idea of what in practice this means for YouTube creators. However in the meantime I can’t help idly wondering if YouTube proper is to become even more focussed on high quality, televisual storytelling content to appeal to the TV set in the living room (and the more lucrative ad dollars it can attract). While YouTube Shorts diverges to become a place with more tolerance for the AI slop type trends such as glass fruit cutting and whatever comes next.

Less than stellar user experience

Part of the reason for the slide of AI down into the trough of disillusionment is because of people’s experience of using it. There have been all sorts of well documented examples of various AI tools behaving in bizarre, comedic and sometimes downright worrying ways. Here are two if you haven’t seen them already:

- shares an unedited conversation with ChatGPT where she asks for its help with analysing some of her own writing

Sam Coates from Sky News shares how ChatGPT seems to think it can time travel:

I’m sure everyone reading this has had some experiences of using AI over the last couple of years - from those who use it daily in their work or personal lives, through to some whose only contact is in the AI-driven search results on Google. Even so, with AI increasingly embedded across all our products and services, it is increasingly part of our online experience.

As for me, well, over the last couple of years, I’ve been using both free and paid AI tools and services in various ways. To name a few:

CoPilot - data analysis and well as powerpoint generation

ChatGPT - ideas generation

Perplexity - research

HeyGen - testing making myself into a video avatar (conclusion - it worked, but I couldn’t get myself to laugh)

DALL-E, Adobe Firefly, Canva - image and visual generation

Zapier - automated saving of each Substack post (following one Substacker losing their entire publication which couldn’t be retrieved)

Notion - diary and task management

Claude - a test to convert my written Substack posts into video scripts

Otter AI - transcription.

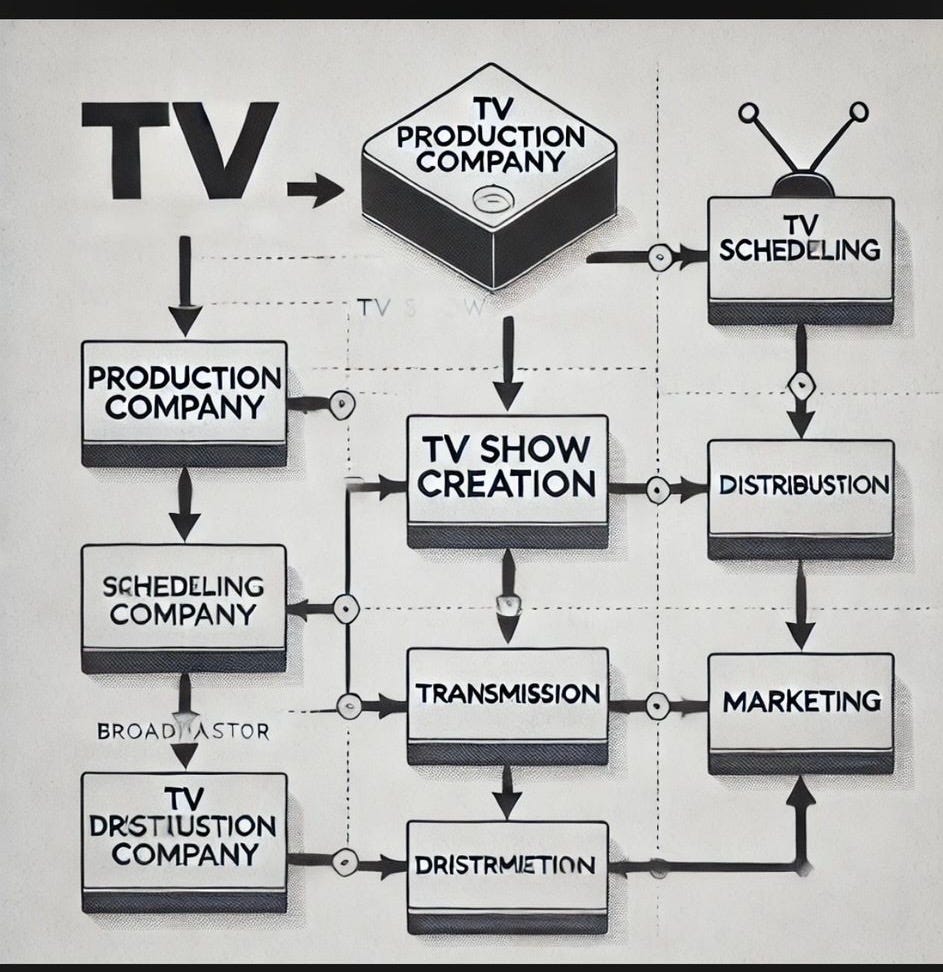

Overall, my experience has been good in places (Perplexity, Claude), so so in others (Zapier’s automation, HeyGen), plus a couple of notable failures that I thought I’d share. Here I tried to use a particular LLM to create a diagram showing the TV process from commissioning to production, scheduling, marketing, transmission and distribution. Despite highly detailed prompts, this is what it produced including errors added to my (correct) spelling and labelling, and arrows often leading nowhere. Each time I corrected the errors it would produce other versions, with new errors added in. All in all, it got very confused.

I’ve also used AI to try to create visuals to illustrate whatever point I’m trying to make - just for a bit of colour to break up the volume of text. Some work better than others, although overall, there is a sameness and dare I say cheapness that I find unappealing (although in response some might say, well what do you expect as you were using the free tier?). This one by DALL-E was to illustrate the breaching of a citadel as a metaphor for TV and the rise of the internet, based on the prompt ‘‘a citadel being breached in the ancient world’.

Other attempts were less passable. This one was my favourite, where I tried to create a representation of the streaming wars, with the network streamers having been beaten by Netflix and Amazon, only for YouTube to be coming over this hill ready to take them on.

Perhaps you can see why I opted to use an image of Jon Snow and Battle of the Bastards as a representation instead (see below)…

On the video generation front. Many are hugely excited by Midjourney, Veo 3 and Sora; however within the context of the various copyright cases questioning the source material they have been trained on, it is hardly surprising users are generating the ouputs that are being shared online.

While I’ll keep looking and testing, thus far generative tools have had limitations on what was produced to the point that the level of effort required to refine prompts as well as correct mistakes can make it more hassle than it was worth.

And in terms of research, some tools are definitely better than others - look at the following two results from Google AI Overview (wrong) and Perplexity (right) to the same question this week:

The significant drop off in traffic to websites thanks to the rise in AI driven search is going to have serious consequences for those in the content creation business, which I wrote about here:

My AI position

Many creators, publishers and writers are sharing their own AI positions (thanks to

for prompting this post to do the same).So, here is my position. I am not (currently) running to AI with unbridled enthusiasm, in part because of the user experience issues outlined above, but also a general unease around AI and how it relates to my work, the content industries and well as our society in general. In summary:

The results are too patchy with errors and inaccuracies - what happens to the mistakes humans can’t or don’t spot?

The emerging model takes traffic, control and revenues away from human creators, IP owners and originators so there needs to be better protections and commercial returns

The current stylistic similarity of the visual and text outputs

The ingratiating tone of some of the tools gives off Uriah Heep vibes; and also encourages anthropomorphism where we attribute human feelings to AI.

With all that in mind, here is my approach to using AI:

Everything I publish is written by me

Anything I share here is based on finding an original source to share and credit rather than relying solely on AI research results.

I’ll continue to test and try out AI same as I’ve done for all sorts of tech, but right now there isn’t a significant user need it has solved for me thus far.

Swing back to trust

After all that, what does this mean for those working in TV production and the wider content creation markets? Certainly AI can and already is helping producers and creators be more productive and efficient, reducing repetitive tasks, automating processes and analysing vast pools of data. So continuing to research, test and implement in this area is important.

Plus, generative AI has real potential in all sorts of TV and content formats where previously CGI and graphics did a lot of the heavy lifting - so say reconstruction, historical moments and the like. However, even here this currently might come with a sting in the tail - because while some broadcasters and networks could be open to these types of shows, the question remains who is liable for ensuring the AI generated outputs in the show have been produced by LLMs trained on copyright-cleared inputs? Is it the broadcaster/network or the production company taking the risk here?

Simultaneously, as the volumes of sameness and slop grows, this is likely to trigger a very natural audience response to look for reliable sources and human storytellers. Increasingly, surely people will seek authenticity, curation and insights from actual humans they can trust - and this is where TV producers and content creators come in.

Further reading:

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Excellent post Jen! Thanks for mentioning Charting Gen AI. We share the same approach to gen AI, and the commitment to keep everything HUMAN♥️MADE in our writing.

This is brilliant Jen, Thank you. 🙏