Cable TV: the costs and volume of ads

In a world with lots of streaming competitors, at what point does the monthly fee plus the amount of ads become unappealing to US subscribers?

This Substack hit another little milestone last week, reaching 2,000 subscribers (well, to be exact, 2,118). Thanks to all of you for subscribing, recommending, and sharing it with your colleagues.

I started posting weekly last September, and then bi-weekly in March. The goal remains the same: to help producers understand the changing nature of the TV, film and digital content markets. So owners of independent production companies and their employees; freelancers, independent producers or people aspiring to these roles; those working in production or commissioning in studios, networks and streamers. Plus of course anyone with an interest in how the TV production world is evolving in the face of technological and behavioural upheaval.

I’ve spent all my career working at the point where TV and the internet meet, and so the ambition for this newsletter is to give you a weekly collection of trends and insights to help you plot your next moves.

It has sparked a whole lot of conversations and if you are interested in discussing anything I cover, do get in touch via hello@businessoftv.com or send me a DM via Substack.

Cable TV subscription fees & adverts: when is too much just too much?

Depressing news from the world of cable TV this week, where a whole number of people have been made redundant both at Warner Bros. Discovery as well as Disney.

And while the story of the decline of cable TV in the US has been much discussed for years, I wanted to talk about a couple of features of the customer experience that may not be apparent to those outside of the US. Conversely, US residents may not be aware of how unusual their set up has been in comparison to other countries.

I’ve written before about trying to avoid applying US insights to the rest of the world:

This has especially been a feature of the first phase of the streaming wars, where the rise of Netflix and the decline of cable TV networks has often been interpreted as a universal tale rather than a specifically US story. By way of a quick summary, the US evolution looked something like:

paid with ads (cable TV) > paid (subscription streaming services) > paid with ads (subscription streaming services ad tier) > free (streaming services with ads)

Conversely the UK journey went something like this:

free or free with ads (linear TV) > free (catch up and archive streaming services) > paid (subscription streaming services).

Obviously this is hugely simplified and ignores players like Sky, but in general, you can see the UK population is well accustomed to not paying for linear TV or streaming services, while in turn the US market has long been acclimatised to paying for both. This is one of the reasons why free services like Tubi are doing so well in the US, and why the UK is a harder territory for them to crack.

When looking at the experience of cable TV subscribers in the US - both in terms of monthly subscription costs as well as the volume of advertising - it is quite stark how different they are compared to other territories.

Ad volume per linear TV hour

Traditionally, the ad load in an hour of linear TV is significantly higher in the US compared with other countries: the average volume of ads per broadcast hour is 16 - 18 minutes in the US with between 5 - 7 breaks, although ad loads and the frequency of breaks varies depending on the channel, the output and time of day. In the UK, it is seven minutes per broadcast hour on average across a day, with two breaks per hour. Ofcom has rules on the amount and distribution of TV advertising (and the US doesn’t have a similar framework).

Monthly subscription costs

The average cable TV package in the US costs $88.29 per month. These subscription costs vary widely, depending on a range of factors such as what is included in the bundle, discounted deals and so on. There are alternatives, such as YouTubeTV’s cable competitor which is $82 per month.

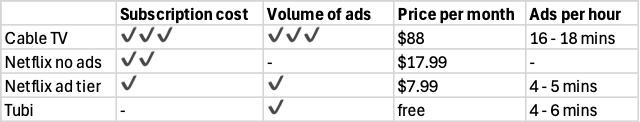

Despite these variables, you can see that in a pre-streaming world with limited choice, it was considered normal for cable TV to cost around $88 a month, and the normal viewing experience was around 16 - 18 minutes of ads per hour. However, now there is a whole range of consumer choice, the differences between streamers and cable TV in terms of costs and ads is much more obvious to audiences.

As examples, the monthly cost of Netflix is less than quarter of the average cable TV package, and for that price, there are no ads to sit through. If you want to pay less, you can get Netflix for 10% of the average monthly cable TV cost, with around 25 - 30% of the ads per hour. Or alternatively Tubi, which costs nothing, and has a similar ad load to Netflix’s ad tier.

Below is a table I made to illustrate this point.

The accepted logic is that users will tolerate ads in exchange for a low enough subscription price. However, if pushed too far either on ad volumes, or subscription price (or both in cable TV’s case), they’ll go elsewhere if the alternative offer is deemed just as good.

Of course, price and ad volumes are only two factors influencing decision making and whether a user feels they are getting value for money. For example, for some users, Netflix might be cheaper, but the cable package includes specific sports or channels and therefore the price is worth it to those fans. In the UK, the comparison here is with Sky, where a monthly package includes Sky Sports for a new subscriber is £35 ($47).

When you look at customer attitudes in the US to advertising, it demonstrates why the cable TV model of (relatively) high monthly subscription fees *plus* a high volume of ads is on shaky ground. According to this research from YouGov last year, only 3% of respondents were comfortable with more than 16+ minutes per hour on streaming platforms. Considering this has been the common ad volume on cable TV in the US for years, it is perhaps hardly surprising when alternatives emerged, they’ve voted with their feet.

All of this brings to mind the concept of the ‘trust thermocline’ that I’ve written about before. In summary:

… users suddenly bulk abandon a product or service and it isn’t clear what caused this mass rejection. But actually, what has happened is people have swallowed the minor changes, the price increases, the cancellation of a much-loved series or two, the lack of sitcoms or longer procedurals, the reduction in films for ‘people like me’, all the while building a perhaps subconscious sense of being taken for granted, until suddenly, they say ‘no more’! And once trust and the associated habits are gone, well, they are very hard to get back.

As John Bull explained (and worth reading his thread in full if you are interested in the concept):

Users and readers will stick to what they know, and use, well beyond the point where they START to lose trust in it. And you won't see that. But they'll only MOVE when they hit the Trust Thermocline. The point where their lack of trust in the product to meet their needs, and the emotional investment they'd made in it, have finally been outweighed by the physical and emotional effort required to abandon it.

Having said all of that, just yesterday

wrote a great piece for on the remaining 60m Americans who have cable packages. The article is worth reading in full, as it includes some useful graphs on the following key trends in the US market:YouTube is the break away winner in the streaming category

Beyond YouTube, the streaming landscape is ‘shockingly stable’ including Netflix

Growth areas are mainly free streamers such as Tubi

While cable subscribers have fallen, broadcast TV is surprisingly resilient.

Focussing on those 60m cable subscribers, he says:

…the fall [of linear TV] is also not nearly as fast as some would have you believe. Moreover, that’s a ton of viewership of traditional TV that needs to migrate to streaming. Really, that’s the fascinating storyline for the rest of this decade: who takes the rest of broadcast and cable TV’s viewing — and who doesn’t.

The Streaming Wars aren’t over. In fact, they may just be entering their most important phase.

And remembering a previous post I wrote focussing on profit margins - where despite the decline of linear TV, these channels still drive healthy profit margins in comparison to streaming.

Even so - and despite this risk of comparing apples with oranges - in broad terms, the earlier table above demonstrates why in the US cable TV had its day in the sun when there was little competition, but once the internet opened the floodgates, this model became hugely vulnerable to disruptive new competitors challenging them on both price and the advertising experience. It also provides further evidence of the difficulties studios and cable networks have in transitioning to this new on demand world, where there is a low tolerance for the high subscription costs and high advertising loads their traditional revenues were built on.

All this has a knock on to producers. In general, production budgets, company revenues, profit margins, and people’s salaries have been built on this model of high price subscriptions and high ad loads, for the volumes of shows that the industry had got used to making to feed all these TV channels (and to deliver these shows requires a certain number of people employed across the industry). This level of disruption to this established way of doing things means there is a contraction in terms of the volume of shows being made and a reduction in budgets and revenues. Basic economics also points to less demand for production people as well as a downward pressure on salaries too.

Local, national and global: understanding the differences

published a very useful report recently into the YouTube landscape, thanks to his access to Tubefilter’s analytics. It is worth reading in full:To pick out just one point which is crucial for TV producers, studios and IP owners to take on board:

“Big Media” content brands like Disney, WBD, Universal, Rockstar Games, and Netflix tend to focus their channels almost entirely on trailers and promo videos. They garner significant traffic (a good amount of it paid-for) but lower engagement, and they tend to be eclipsed by Creator-led YouTube natives like MrBeast, The Royalty Family, The Outdoor Boys, and Alan’s Universe, or YouTube-centric corporate brands such as VEVO (corporately owned, yet an organic YouTube master). However, this does not have to be true.

If and when Big Media brands like Universal Studios, Disney, Nickelodeon, and Warner Bros Discovery use YouTube the way Creators and native YouTube brands do — content first, promotion second — they could and likely would be the world’s biggest Creators.

This is undoubtably true and not only for big media brands - the opportunity is there for all producers to step into this space and build their own fandoms via platforms like YouTube.

However, there is another dimension within Evan’s report I thought important to draw your attention to, which is the differences between territories and countries around the world. Ian Whittaker summarised this point in response to Evan’s piece:

The geographical imbalance is very striking. 15 out of the top 50 channels (on my count on the move) are Indian and 25 from SE and East Asia in total, with Vietnam also prominent. Conversely, only 5 are European (and one of those is Russian) with none from the UK or Italy, and one each from Germany, France and Spain. YouTube channels look to be doing especially well in specific areas.

Leading on from that, this suggests that the "YouTube is TV" depends on where you sit in the world. In some places, yes; in other areas (Europe springs to mind) less so. The US is the big question here - how much of the c 12%+ share is content creators' channels and how much is music videos, other channels' content and NFL?

In terms of consumer attitudes to ad loads in different territories, the YouGov research is worth a read. While this research is about attitudes and tolerance to ad loads on streaming platforms, perhaps the also demonstrate why the high(er) ad loads of linear TV faces a challenge, especially when it comes with a monthly subscription cost as well. For example, across all 17 countries polled, only 4% would accept more than 16 minutes of ads per hour. In the US, only 3% were happy with this amount, while India, Indonesia and the UAE were most comfortable at 9%.

The case study of Bluey

mentioned in his report into YouTube that there are several media brands who have demonstrated it is possible to ride two horses at once and by doing so, makes the whole ecosystem of an IP bigger:…BBC Studios proves this new-age Big Media thinking with Bluey - popular on Disney+, while simultaneously huge on YouTube. WWE also distributes a significant amount of long-form content on their channel, while remaining a powerhouse on Pay TV and streaming services.

For more insights on this, I’d really recommend listening to the Kids Media Podcast episode below from

, Jo Redfern and Andy Williams, joined by Jasmine Dawson from BBC Studios talking about the success of Bluey.Fraudsters targeting screenwriters

This article in Deadline caught my eye, so thought I’d share it just to increase awareness. In a nutshell, scammers have been using Stage32 to contact script writers pretended to be big name producers, and then ask for sums of money on the promise of a potential future production.

Obviously scammers are found in all walks of life, and the targeting of creative people by dangling the carrot of a commission or a sale is not uncommon. There are numerous instances of it in other creative industries, and book publishing has been a particular field they have been targeting for some time. Indeed, there is an entire website dedicated to raising fiction writers and publishers’ awareness of the latest scams and tactics of these fraudsters.

Creators who are quitting

There has been quite a little rumble of late about the number of creators who have decided to step back from the grind of producing content for their channels or feeds.

This piece by

is worth your time on the trend, and explains how each creator who decides they either need a break or want to stop all together have their own personal reasons for doing it. It can range from lifestyle, burnout, seeking new opportunities - or for some, they’ve made more than enough money out of being a creator and are looking for something new to excite them.For those in TV, especially if working on shows that have daily or weekly TX schedule, then the notion of burnout is a familiar concept. The difference for those in TV, is once you’ve done your stint on a particular production treadmill, it is possible to go and work on something different - so perhaps a different production but with the same schedule, or instead go to a completely different type of show. However, when you are a creator, you are a media empire in your own right, and so there isn’t another job, show or output you can swap to - this is your channel, your output, and your business - so your choices are more limited.

Equally, because it is yours, you are in complete control of your own decisions (unless you’ve got partners, brands or financiers you are answerable to, and then therefore you have to find ways to unwind these relationships).

wrote this piece on creator burnout, and perhaps how TV offers solutions to this challenge:And some have already done just that. Last week in a post about food creators I wrote about Australian/Thai cook Marion Grasby who has decided to stop making as many YouTube cooking videos, to concentrate on doing a TV series produced by her own company.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that YouTube hasn’t worked for her, and therefore traditional media saves the day - rather, it is possible that the volume of video recipes she’s got in her archive will tick along nicely earning money for her for years to come and so she is free to concentrate on other things for a time. After all, users will always be searching for the best Chinese rice recipe, and whether it is recent or several years old is irrelevant. Of course, some creators are stopping doing a particular activity because it isn’t making the money they hoped.

Finally, one last point it is important to acknowledge. TV is a hugely sociable industry to work in; bringing together teams with their own expertise to work together to create something bold and interesting for audiences. The collaborative and social nature of TV is something that attracted many people in the first place to join the industry. Conversely, the solitary nature of being a creator - especially one that hasn’t yet hit the big time - can be a turnoff to those who come from the TV production market.

Other interesting reads

Stream Insider: 66% see YouTube as destination for long-form movies, TV shows

Ampere: Subscribe, stack, churn, repeat. What do younger viewers want from streaming platforms? (answer: watch more video, buy more video, subscribe to more streaming services, but are less loyal and have a high churn rate than other demographics).

- : Can AI Lift Hollywood Out of Its Funk? Sequoia & Thrive Are Believers

The Streaming Lab: AI in Indian Streaming: How Local Platforms and Media Giants Leverage AI

Hollywood Reporter on how Netflix Prioritises UK Viewers in Local Content Strategy (thanks to

)

Listen: All3Media’s SVOD, AVOD and FAST strategy

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Thanks for the mention, Jen :-)