A YouTube channel bought back from its TV network; Vimeo launches a new streaming service

And being wary when applying US TV insights to other territories, plus a little on the costs of AI video tools for creators.

Before starting, a quick note of apology - I took a holiday last week (but neglected to mention it in my last newsletter) and then was struck down by the most god-awful bug so have not published twice this week as is routine. Normal services shall resume next week!

This week I’ve written about:

A digital commission being purchased back from its broadcaster,

Will broadcasters sell ads on third party YouTube channels similar to how they sell advertising for other TV networks,

Vimeo launching a new turnkey streaming platform for creators (and I assume, TV production companies)

One size doesn’t fit all - a reminder to be careful applying US data and TV market insights to other territories

How much it costs for indie filmmakers to use AI tools to generate live action.

And as always, send feedback - especially if there are particular things to want to know more about - to hello@businessoftv.com.

If this is your first time reading, please do subscribe, you’ll be joining over 1,400, 1,500 other TV, film and online content professionals from across the world.

—

Before getting going, here is another little reminder to get your ticket to Create London on April 30th and use the discount code below.

Join the Evolution of the Creator Economy at C21’s Create London Festival

C21’s Create London Festival is a one-day event on April 30, celebrating the creator economy and bringing together creators, TV/film producers, digital platforms, commercial partners, commissioning brands, and AI technologies.

Be part of the creator economy’s next chapter - secure your place today HERE!

Exclusive Offer: Business of TV subscribers receive 20% off the current ticket price with code VIP20 at checkout.

Mashed purchased back from Channel 4 by its production company

Rather joyously, Mashed - one of the first Channel 4 digital commissions after multiplatform activities were merged in with the TV commissioning division back in 2010 - is taking on a whole new life having been purchased back from Channel 4. The founders of the original production company (The Connected Set) created a new animation label Spud Gun Studios, which will take ownership of the brand and be responsible for its growth.

There are several reasons this is notable. Firstly, many of the digital projects commissioned by broadcasters in the 2000s and 2010s were rarely just video. Instead they often involved websites, apps, games as well as content, which can make it tricky for a production company to buy back, as often developers or other third parties were involved, and production companies usually don’t have the technical skills to run these types of products (never mind whether there is a business model).

So Mashed was a little unusual in that it was a video commission, but what made it more unusual was that it had its own channel on YouTube. As an explainer, when broadcasters commission digital video, it typically lives on a broadcaster-branded and owned channel. So while huge juggernaut shows might have their own channels (sometimes owned and run by the production company), it is more common for video from different shows and production companies to be aggregated together under one channel such as Channel 4 Documentaries or Comedy Blaps. This is for the very good reason it avoids broadcasters ending up with zillions of channels that need to be fed and maintained long after the TV show has ended. In that sense, you can see how Mashed has been an outlier in terms of Channel 4’s overall YouTube and digital content strategy, so it is a tribute to the production company and Channel 4 for having nurtured it thus far.

Why buy it back? Well, it has a subscriber base of 5m and 1.8bn views and a clear globally appealing proposition focussed on animation and gaming. There is a lively community with weekly content drops and a solid network of animators and cartoonists. Put all this together, and Mashed is something worth buying with real longevity and commercial potential the same as other YouTube native brands.

And perhaps Spud Gun Studios has half an eye on the trajectory of Glitch Productions, the Australian animation studio that has had huge success with its adult animation series 'The Amazing Digital Circus' which grew out of its YouTube fanbase before being acquired by Netflix.

Sadly, I have no further intel on the deal which is confidential, however the news did make me wonder how clean the break is between Channel 4 and Mashed. Will the channel be completely standalone on YouTube, or will it remain under the Channel 4 network, which isn’t obvious to users but enables all channels under the umbrella to benefit from the YouTube algorithm looking more favourably on them as a collective? Perhaps even more significantly, will Channel 4 sell ads or sponsorship on Mashed’s YouTube channel? In the same way over the past years Channel 4 has done deals to sell advertising for other broadcast TV channels (C4’s Ad Sales team look after UKTV and Warner Bros. Discovery), building out ad inventory volume by adding more channels on YouTube would be a natural progression.

Speaking in generalities (rather specifically in relation to Channel 4 and Mashed), the reason it might be appealing to a YouTube channel to have a third party sales team sell their ads is because usually these sales houses sells advertising at a higher price point that YouTube ads, and also in theory can attract more valuable brands for sponsorship. One question here is what territories any third party sales house sells into versus where a channel’s audiences is - so if a sales house targets the UK but the bulk of the audience is ex-UK, then that may strike a line through the whole concept. In addition, for an individual channel brand, the question is whether the money stacks up. Leaving sponsorship and brand deals to one side, if the channel stick solely with YouTube ads, they keep 55% of the revenue themselves after YouTube takes its share. If the sales house sell the ads at a higher price (and any unsold inventory runs YouTube ads), they will take a percentage of what they sell. For simplicity’s sake, if the sales house’s commission is 10%, and can sell at least double the price of YouTube, then that makes a whole lot of sense to a channel. If however, the sales team takes 20% and they can only sell at a quarter more the price than YouTube, the it all quickly falls apart.

While in this scenario, a channel would remain independently operated except for the ads sales element, we are already seeing the expansion of channel portfolios by MCNs (multichannel networks). This follows the same pattern as TV-land where broadcasters added channels or acquired other networks to expand their reach and revenues in an increasingly fragmented market, such as when in 2018 Discovery acquired Scripps to create a combined portfolio of channels like Animal Planet, Food Network and HGTV.

An example of this trend is Little Dot’s announcement earlier this year to double its owned and operated channels to 160, as well as targeting specific territories including Germany and Spain. Interestingly, they are also going to start using a consumer-facing brand ‘Little Dot Channels’ to help audiences recognise the channels under their network.

Little Dot also published their current content acquisitions wishlist which is worth exploring if you have programming you are interested in distributing.

Vimeo to allow creators to launch their own Netflix-esque streamer

Vimeo announced last week they are offering a turnkey solution to allow creators - although perhaps that could also mean production companies - to launch their own streaming services. The service includes a fairly comprehensive suite of functionality, as listed in the Hollywood Reporter:

Called Vimeo Streaming, it will let any video creator launch a service and apps without any coding experience. The service includes tiered membership options, including access to live events and merchandise; custom video bumpers to promote specific projects or campaigns; piracy protection; advanced data analytics; and AI-powered translations to enable global reach.

It was also noted that they are offering AI-powered language translation - another instance highlighting the importance of translation and dubbing to reach bigger non-English speaking audiences.

This is an interesting announcement and reflects the desire for some creators to diversify their income, water down their reliance on YouTube, create more opportunities to reach wider audiences, and also create a premium offering for their super fans. It is likely this type of offering is for much more established creators or brands rather than those starting out, however it is indicative of the growing professionalisation of this market.

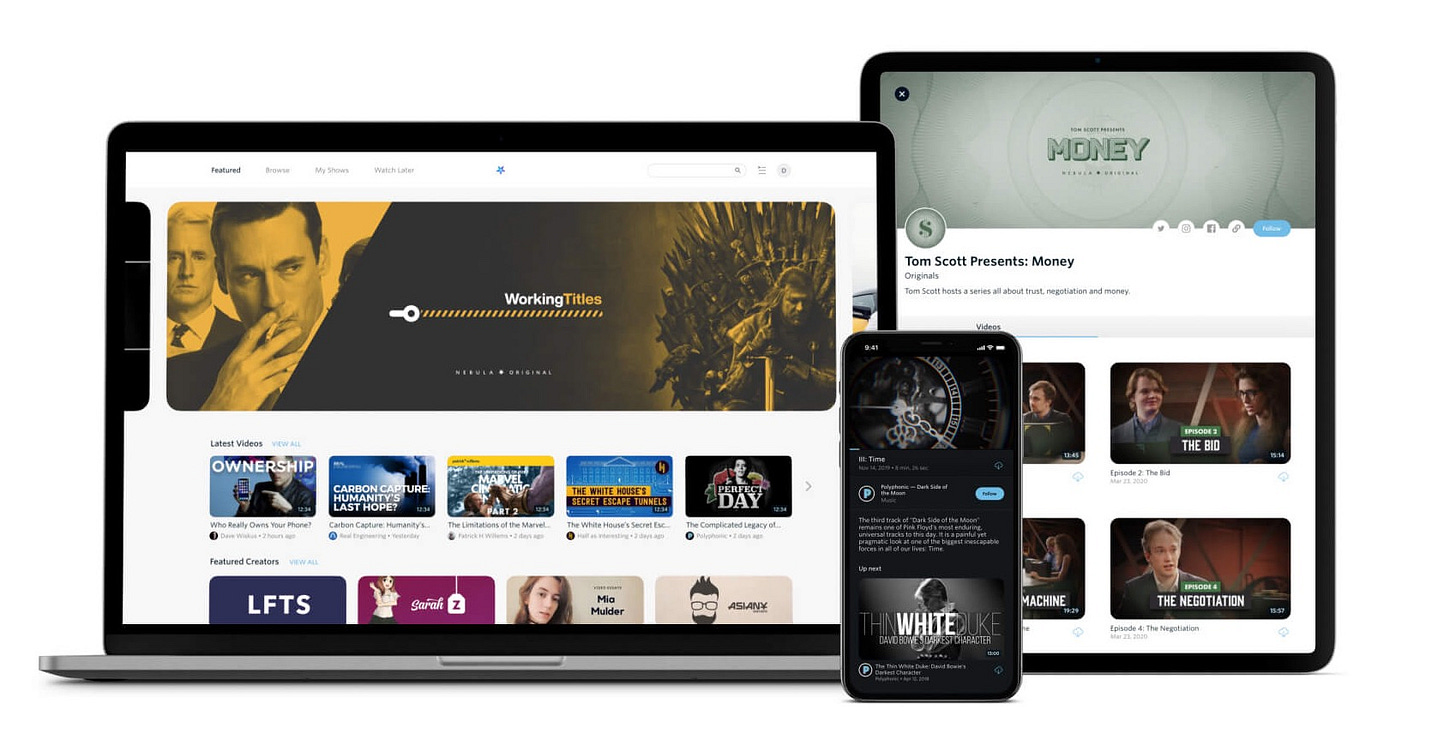

In a similar vein, Nebula.tv is a ‘creator-owned and operated video-on-demand streaming service. It offers videos, podcasts, and classes, with a focus on ad-free viewing and exclusive content from its roster of creators.’

While this is a different offering to Vimeo Streaming - Nebula costs $6 per month gives you access to all the content on the platform, rather than individual creators - it still is part of this growth area for creators to professionalise their offerings while also reducing their reliance on YouTube.

Being careful applying US data to other territories

For those of us not in the US (and indeed, for those in the US, something to be aware of), there is a danger of applying US data and the US TV experience universally, rather than being aware that it often can be specific to the US market.

This has certainly been true in the streaming wars narrative. To give a very high level explainer, in the US, TV networks have long relied on a significant chunk of their revenues coming from regionally carved up carriage deals with cable and satellite providers. Below is an old map showing the top internet providers by state, which often people got bundled with their TV package as part of the deal with a provider.

These internet/cable providers all sign deals with the various networks to be able to carry their channels and content - called affiliate fees and carriage deals. And these deals continue to make up a significant percentage of income for the studios and networks. As reported in 2023:

U.S. affiliate fees for Disney account for about 17% of the company’s revenue. By comparison, affiliate fees represent 48% of Fox’s revenue, 22% of Comcast NBCUniversal’s revenue and 21% for both Warner Bros. Discovery and Paramount.

In comparison, for a country like the UK, while there are TV regions to sell advertising, as well as national channels like STV, S4C and BBC Alba, they aren’t bundled in with third party cable or internet providers in the same way. Instead, when a broadcaster signs a carriage deal with Sky, Virgin, Freesat or EETV, they are agreeing to treat the UK as one territory.

This is an important context for why if you were a US executive sitting in ABC, NBC, Discovery or Disney back in the 2000s, the idea of launching a comprehensive nationwide online catch-up video on demand service could be considered nigh on impossible - you would be driving a coach and horses straight through multiple lucrative carriage deals that would have not only crippled your income but probably resulted in lawsuits and the like.

In contrast, back in 2006, Channel 4 and the BBC didn’t have the same hurdle to jump, and therefore were much freer in being able to offer comprehensive catch-up on their new video on demand services - meaning if you missed anything on the live TV channel, you would be able to view it online a short time after. There were exceptions - deals needed to be negotiated with individual US studios for American acquisitions, plus some films and sport were excluded. And the UK population quickly got used to the idea of catch-up being a routine offering, and if a show wasn’t available it would have been a surprise. Plus you didn’t need to buy a particular service or piece of technology to access it - it was freely available online, via apps or via TV providers like Sky and Virgin, smart TVs such as Samsung, Streaming devices like Roku, games consoles like Xbox.

This key difference meant that streaming emerged in a completely different way in the US, where independent companies like Hulu and Netflix built the platforms and hoovered up the archive rights. This taught US viewers that there was a huge volume of content available on these streaming platforms, but they weren’t comprehensive TV catch up services as they were and are in the UK. Instead, US audiences bought DVR services like TiVo to catch up on missed broadcast shows.

The rest of the streaming wars story is fairly well known. Networks started to realise that the streamers were cuckoos in the nest, so pulled their assets off the platforms and built their own walled video on demand gardens to compete, all the while the growth in alternative streaming providers that they in part helped enable continued to eat away at their core broadcast business.

The reason for mentioning all of this is that it has often been the case that the US story has often been applied to other territories, when in reality, each country has its own quirks and differences. Using the UK as an example, the streaming strategies of all the broadcasters here, thanks to our very different market conditions, have been able to be much more future-looking when compared with the US (although because of to the globalised nature of streamers, are now facing similar pressures on viewers and revenues).

There have been a few other instances recently that show a similar potential to rely on US data and market conditions as being representative of other territories:

YouTube viewing figures

Nielsen’s The Gauge is such a helpful monthly check in on audience share of TV viewing in the US, and the YouTube growth has been one to watch. However recently, Thinkbox flagged that YouTube’s share of TV viewing is higher in the US compared with the UK - 11% vs 7%. I wrote previously on Thinkbox’s TV Trends report here:

Viewing figures for Beast Games

I wrote about Beast Games perhaps being a mid-ranking performer, based on analysis by

, and went on to wonder whether an equally important metric might be the show’s success in India (this data hasn’t been released by Amazon). After all, it is Amazon’s key growth territory, and Mr Beast has a huge following there which he deliberated targeted, in part through his early focus on dubbing and subtitling all his videos.So in this instance, if looked at through a US lens, then the show might be a meh - but for Amazon’s ROI, if it did the business in India, it might be a major hit for them.

Local content for local audiences or accessing big global markets?

Another example is how we evaluate success of titles on global streaming platforms, especially in our world in uneven data sets across different territories. A few weeks ago I saw this piece by

where he questions ’ analysis in about the popularity of non-English titles on streaming platforms.As ESG said:

This is one of Netflix’s biggest innovations, increasing its total available market to the entire globe (minus China). Even better, if a company can make a show in one country and stream it globally, it can have a better return on investment per show.

The problem is this works out better in theory than practice.

Just because a global media company can reach the entire world doesn’t mean that customers want to watch foreign-language content now. (Or, to be specific, non-American foreign content, since many American films and TV shows still play globally.)

Indeed, foreign-language content barely penetrates the U.S. market. Netflix touted that 14 percent of U.S. viewers watched foreign-language content last year . . . and the U.S. population has 14 percent foreign-born residents. As I wrote for The Ankler way back in 2022, even Asian viewers mostly like watching content from other Asian countries.

In response, Rick Ellis took the view that the companies with global streamers (so Disney, increasingly WBD as it rolls out Max, and obviously Netflix and Amazon) are commissioning territory-specific content to appeal to that territory, rather than to appeal to the US market:

[Disney’s] producing South Korean shows for the same reason Netflix is doing it. It's a response to the marketplace. It's why Disney is also spending on original content in Japan, India and Latin America. And why Warner Bros. Discovery continues to invest in original programming in Europe. Local subscribers demand local-ish programming, and producing it yourself allows you to easily share it globally. Sure, the success of Squid Games was impressive. But no streamer - Netflix included - thought that success meant they should produce more South Korean shows for the U.S. market. But it did mean there was a potential global audience for some shows, if you're extremely lucky and focus on content with global themes.

I think both of these pieces touch on what is going to continue to be a big theme over the coming years; that is, how to navigate building global streaming services with audiences that also have an expectation around localness. And off the back of that, how to find local titles that might also achieve the ultimate nirvana of appealing to global audiences, even if they are niche. For producers, understanding this local versus global (and local that can translate to global niches) spectrum will be important.

TV has historically been a local business - yes of course imported (usually meaning Hollywood) series and films have been a scheduling staple, however it has always been important for broadcasters to meet audiences’ expectations to see programming that reflects their lives and their world.

Meanwhile, streamers have the ability to create global and local offerings: shows to reach huge worldwide audiences as well as shows created specifically for particular territories. Some of the latter titles might then find small global audiences who are interested in South Korean shows, for example. So yes a niche that won’t trouble the top 10 lists, but in aggregate might make a meaningful set of numbers in addition to the viewing figures in the primary territory these shows were commissioned for.

And you never know, one of the shows might become a stand out smash hit that crosses borders like Squid Game.

It is worth reading them both - Rick Ellis’ piece is here and The Ankler piece is here.

Cost analysis for AI as a production tool

The internet is full of people testing out and comparing all of the latest AI video tools, and last week I spotted a discussion on X that I thought worth sharing. It was from @alanxtruc who's been in the indie filmmaking scene for 25 years. Having watched a recent demo of the Kling 2.0 video tool (above), he did the following post to explain the plausibility of the tool to be used to make live action films by individual creators rather than studios:

I just watched this one-minute-thirty Kling 2.0 Master video featuring motorcycles, composed of nearly 100 generated shots, each under 5 seconds. With a 1 in 10 success ratio, which is standard in fiction filmmaking and possibly even a little optimistic here, that means generating around 1000 shots. Each one costs about 100 credits for 5 seconds, or roughly 100,000 credits in total. No subscription plan offers enough credits for that kind of production. Even the 728 dollar yearly plan only provides 96,000 credits over twelve months. If you need 1000 clips now, you have to buy credits.

To take it a step further, this is all for a 90 second video. To produce say 60 minutes of action using the tool using his formula would cost $50,000 in credits. Irrespective of the quality question (never mind the copyright of the material that the LLM has been trained on), this obviously is far cheaper than a studio live action production budget, but also remains way out of reach of the majority of individual creators who are enthusing about the potential to make films using these tools.

The conversation between indie film makers is worth reading, as it reflects exploratory nature of how filmmakers are using and thinking about these tools, as well as the ongoing jostling between the various AI companies over capabilities, quality and cost. Plus how far away these tools are from plausibly being used in a consumer facing cinema production (as opposed to storyboarding and ideas generation).

On the point of AI in TV and film production, I’d really recommend reading Alan Wolk this week - it is very brief. He includes a good observation that after the frenzy of 2024, that things in TV land are a little less chaotic so far this year, but issues a warning about this being the calm before the coming AI storm. As he says about AI for those in TV:

Which means that what you need to do more than anything is just to stay on top of it.

Really stay on top of it.

Not just a couple of articles you see posted on LinkedIn or the New York Times website, but really dive in. Assign people to figure out what is being done that may affect you and who is doing it. Make sure you know what’s possible and then, when the next round of action starts up, you won’t get taken by surprise.

He also makes the continued important point about measurement and what counts as a ‘view’:

That has everything to do with the arms race that has them all picking shorter and more forced definitions of what a “view” actually is. And how that virus is spreading to television, where Netflix has moved all the way from a view is someone who has completed 70% of a given show to the current definition of someone who has watched for just two minutes.

Increasingly as convergence means TV, social, YouTube are all starting to merge, then metrics and performance will need to get an awful lot better in terms of proving value to advertisers. It is something I’ve mentioned before, and will come back to in the future.

Join the Subscriber chat

I use Substack to publish this newsletter, which as well as being an email tool also has a social network. Some of you are already registered Substack users, but many of you aren’t so you only get this email. It may be that you don’t want to add yet another social platform to your life - who could blame you - however I would say there it is a lively and thoughtful TV and film production community here, and has a feeling of the early days of Twitter.

As well as the social network function (called Notes), Substack newsletters also have a conversation space for subscribers—kind of like a group chat or live hangout. I’ve only sent one message which was last week, to say I was going on holiday to will miss a week. If you fancy joining, click the button to Join Chat and there is also more information on how to use it below.

How to get started

Get the Substack app by clicking this link or the button below. New chat threads won’t be sent sent via email, so turn on push notifications so you don’t miss conversation as it happens. You can also access chat on the web.

Open the app and tap the Chat icon. It looks like two bubbles in the bottom bar, and you’ll see a row for my chat inside.

That’s it! If you have any issues, check out Substack’s FAQ.

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.