Are there psychological barriers stopping TV producers jumping into the creator economy?

Plus thoughts on Create London 2025; an example of a TV production company using YouTube to maximise reach; and my favourite Substack publications.

If this is your first time reading, please do subscribe, you’ll be joining over 1,600 other TV, film and online content professionals from across the world.

Some thoughts on Create London 2025

The first Create London event was on Wednesday, and it was great to meet so many of you in person. I had the privilege of moderating the opening session ‘strategies for success in the creator economy’, and the panellists were:

Helen O’Donnell, director of development at BBC Studios TalentWorks

Abi Clarke, stand-up comedian and presenter

George Cowin, co-founder and CEO of Cowshed Collective

Beth Heard, creators agent for United Talent Agency.

They all have a wealth of experience and a few key standout points included:

Abi started out on TikTok, where she has 980k followers; Instagram 350k, and latterly on YouTube with 218m views and 605 followers

She shared her experiences and how in hindsight it would have been beneficial to have a goal and a plan before starting out - she said she started with sketches during lockdown which really helped her build her audience and go viral, however in the longer term that didn’t necessarily help her grow her stand-up career after the end of covid and the world opened up again (she’s currently on tour so do book tickets)

Beth talked about the level of support a creator who signs with UTA gets, including agents specialising in podcasting, events, merchandising plus legal and financial expertise. The takeaway here is for creators with enough of a following to sign up to an agency like UTA, there is a serious level of professionalisation as well as money in this space. She also talked about the benefits of being focussed, using Jack Edwards as example where he narrowed down his niche to just being books rather than the wider study genre he started out in.

George’s Cowshed Collective is one of the exciting new style entertainment companies working across creators, direct to consumer, owned IP, production and social - they produce the Sidemen show Inside, plus were behind much of the success of Foot Asylum’s YouTube channel which set the model for many sports and youth oriented brands. He talked about one example of a dating channel they are due to launch, which includes original content as well as archive dating shows (do get in touch with Cowshed if you have any titles that they might be able to acquire).

Helen’s worked with creators for a really long time, so has watched the market grow and mature at close quarters. BBC Studios TalentWorks runs the creators in residence programme, where they bring creators close to big brands such as Doctor Who and Bluey. One of her key takeaways is that the desire to categorise and label different activities - TV vs creators, platforms, genres, storytelling types and so on - is holding us all back, and we just need move beyond this approach as it isn’t how audiences view the world.

Another subject that came up was the power of WhatsApp as a mechanism to build audiences and also for viral sharing of content. I wrote about this in depth a few months ago but a quick summary:

… the upside of WhatsApp channels is they create a mechanism to directly reach your audience, but doesn’t come with the significant responsibility of managing a full, live, online community.

Other great sessions at the event covered brands, AI and sports. While much of the conversation about revenues, brand partnerships and the like were a source of optimism, Ben Zand (of Zandland) shared a note of caution around investigative journalism. In a nutshell, investigations cost a lot of money, and the creator model either in terms of ad revenue or brand partnerships aren’t there to support these costs. This is something I’ve touched on before, and the example below of Candour Productions on YouTube reflects the continued importance of TV commissioning to fund investigative journalism.

Separately, if you get the opportunity to hear Sidemen manager and founder of Arcade Group Jordan Schwarzenberger speak, I’d urge you to attend. His insight and clarity of thought about future media trends is impressive. If he continues on his current trajectory (he’s 27!) he will be a major global player in the media landscape for years to come.

I’ll come back to some of my other takeaways over the next few weeks, but in the meantime, it was great to see so many TV producers in the room, because as we know the level of TV commissioning can be somewhat of a dribble compared to the previous firehose, and being open to new direct to consumer opportunities is pretty crucial for creatives and producers of all types.

Are there psychological barriers blocking TV people getting into the creator market?

Recently I’ve written two posts about producers and YouTube - one theorising why freelancers haven’t yet stepped into this space and the second on why production companies haven’t done so en masse either. You can read them both here:

And while these cover lots of reasons why not - misconceptions about the platform, economic, structural and cultural blockers - I’ve not yet touched on the psychological. Is it an elephant in the room for why so many producers haven’t grabbed the creator market with both hands?

TV by its very nature is broad (it is broadcasting after all), which can be a game of absolutes and sweeping generalisations. Every producer will have heard commissioners saying that a certain subject or theme ‘doesn’t work’ or 'people won’t watch it’ only for someone somewhere to commission something on that particular subject and then suddenly it becomes something that does work and people will watch it - indeed, give me 10 eps and can I have them yesterday…

Similarly, we all make sweeping generalisations about user behaviours. ‘No one watches TV’ or ‘everyone is watching YouTube’ or ‘young people are all on TikTok’ and so on.

However, those twin pillars of the disruption era - convergence and fragmentation - involves the merging together of what were separate markets and media types, while simultaneously smashing up what was broad mass market into smaller shapeshifting niches. C21’s David Jenkinson at Create London defined the creator economy as being for anyone looking to create a direct to consumer relationship, without having to go via a commissioner, funder or gatekeeper of some description.

In this new world, sweeping generalisations aren’t a helpful mindset in finding opportunities. To succeed in this new direct to consumer space involves hunting down and targeting a niche, a sub culture, an interest group or a hobby, a fandom or a tribe. So yes, of course there are still big broad successes out there, however increasingly where you’ll find your edge will be in hunting a niche and building an audience and community around whatever that may be.

The good news is that potential niches are limitless. However, it can make it hard to talk about the creator market in general terms, as there are no clearly defined set of guardrails or rules to follow. This week’s

has expanded on this concept and is worth reading in full, as she says:Creator businesses vary widely. A beauty creator, for instance, might make $500,000 a year from affiliate links while a TikTok comedian doesn’t earn any money that way. And when it comes to brand deals, creators charge a range of rates based on their reach, engagement and the FOMO factor. One creator rep tells me that a typical deal — let’s say a TikTok for a brand that’s syndicated to Instagram Reels, with the creator posting the video exclusively to their own channels for two weeks and the brand paying to use for 30 days after — could fetch one of his agency’s smaller creators $7,500. A top creator, meanwhile, could charge $125,000 for the same work.

So a creator business can:

work across any platform (or more likely, mix of platforms)

any format, or mix of formats

any genre or style, or any mix of genres or styles

make money in a range of different ways

be a flash in the pan or have real longevity

remain small and niche or grow to be a media empire of the future.

This means a creator business can make money in a whole host of ways:

Advertising income from AdSense - much more reliable for long form channels on YouTube than short form on Instagram and TikTok

Brand deals - more common for creators who are personalities, comedians and talent (so Abi Clarke works with brands on her channels)

Affiliate sales - for certain types of creator channels, then revenues of third party products works well, such as beauty, food, home interiors

Product or services - selling courses, tutorials or individual services are a big niche, such as Miss Excel who was reported to make $2m selling Excel spreadsheet tutorials in 2023

Content licensing - various creators have licensed their content to other platforms. We’ve discussed Glitch previous selling ‘The Amazing Digital Circus’ to Netflix, but also many others such as Ms Rachel and Netflix, or Alan Chikin Chow licensing Alan’s Universe to Roku. There is going to a lot more activity of this type.

Events and tickets - in person events have been big business in creator-land for well over a decade

Subscriptions or memberships - these come in a range of forms, such as ad-free podcasts or streaming, or joining a club or community such as a Discord channel.

As a result, the individualistic nature of the creator market means it is difficult to categorise or make generalisations. Indeed, it makes trying to share takeaways in a conference session like the one above at Create London tricky, as each sentence usually starts with ‘well, it depends on the creator…'

The relative lack of clear genres and categories in the direct to consumer world is a crucial concept for TV producers to understand, as once you’ve grasped the rule-less, permission-less, boundary-less nature of this market, the more likely lightbulbs will start going off in your head. After all, in this space the only limit on success is your ideas, dedication and willingness to keep going until you hit a rich seam with audiences.

So for example, a misconception with TV production professionals is that to succeed on YouTube requires you to broadcast yourself similar to how comedy creators do; after all, the platform’s strapline was exactly this until 2012.

And frankly, for many people in TV production, the very idea of being front of camera makes them come out in a rash. However, this isn’t an essential requirement to build a successful creator business - indeed many YouTube channels don’t feature any human at all. For example, Fern is one of the wave of faceless YouTube channels grabbing attention of late - including MrBeast name checking it as a channel to watch.

I think this demonstrates the wider issue with people looking to categorise in a space where categories don’t really exist. And hunting content types or genres on YouTube is a natural part of being conditioned by TV. Is it fact ent or features? Entertainment or documentary? Daytime or primetime? A single or a series? A returnable or a short run?

It is also natural for humans to seek boundaries. When I did my MBA one of the most interesting parts was around human psychology, and a key concept was how important it is to know where the boundaries are. So in the world of work, if you don’t give team members a boundary for their role (which some managers believe is a way to empower people), then the very human response is often to retreat into a fairly narrow area, because despite the intention, many of us don’t take the lack of clear boundaries as a licence to roam freely. Instead, many of us worry we are going to screw up, so this nervousness at the lack of clear boundaries makes us retreat further than is actually necessary. Conversely, if you give people permission to do whatever they want within a specific boundary, then they will be empowered to do their best work right up to the edge.

And this is the challenge with the direct to consumer market as there simply aren’t boundaries. There is no one setting rules on content types. No gatekeeper. No regulation beyond the laws of the land especially those related to copyright or being caught somehow trying to game the algorithm. This is a permissionless environment where anything goes. So if you want to broadcast yourself you can. Equally, if you’d like to make a channel where you never appear, then that too. The only boundary is your creativity and scale of your ambition.

As the market grows and matures, then some loose categories are starting to emerge, although they don’t behave in the same way as TV genres or categories.

quotes Doug Landers (from creator talent agency Greenlight Group) who views creators in two lanes:…those who make long-form YouTube content and those who make short-form TikTok and Instagram content. For those long-form creators, AdSense, Google’s monetization tool, can make up about two-thirds of revenue. Short-form creators, meanwhile, might only make between 10 percent and 20 percent from AdSense and will instead earn most of their money from brand deals.

So while a few lanes are emerging, in general this boundary-less environment can make some people thrilled and hungry to devour such a lack of rules. But it can also trigger a different response in others where they retreat to the centre out of unease or nervousness.

If these psychological barriers do exist, then as Helen O’Donnell said at Create London, we all need to just get over them as they are just getting in the road and blocking TV producers and creatives - some of the greatest storytellers in the world - stepping into the direct to consumer market where there are audiences ready and waiting.

A TV production company using YouTube to maximise reach

Candour Productions have made a series of four films on the UK’s grooming gangs scandal going back more than 20 years, with the most recent film going out this week on Channel 4.

On social, yesterday I spotted a little post linking to their YouTube channel CandourDocs, promoting that the three previous films from 2004, 2010 and 2013 are available to watch in full.

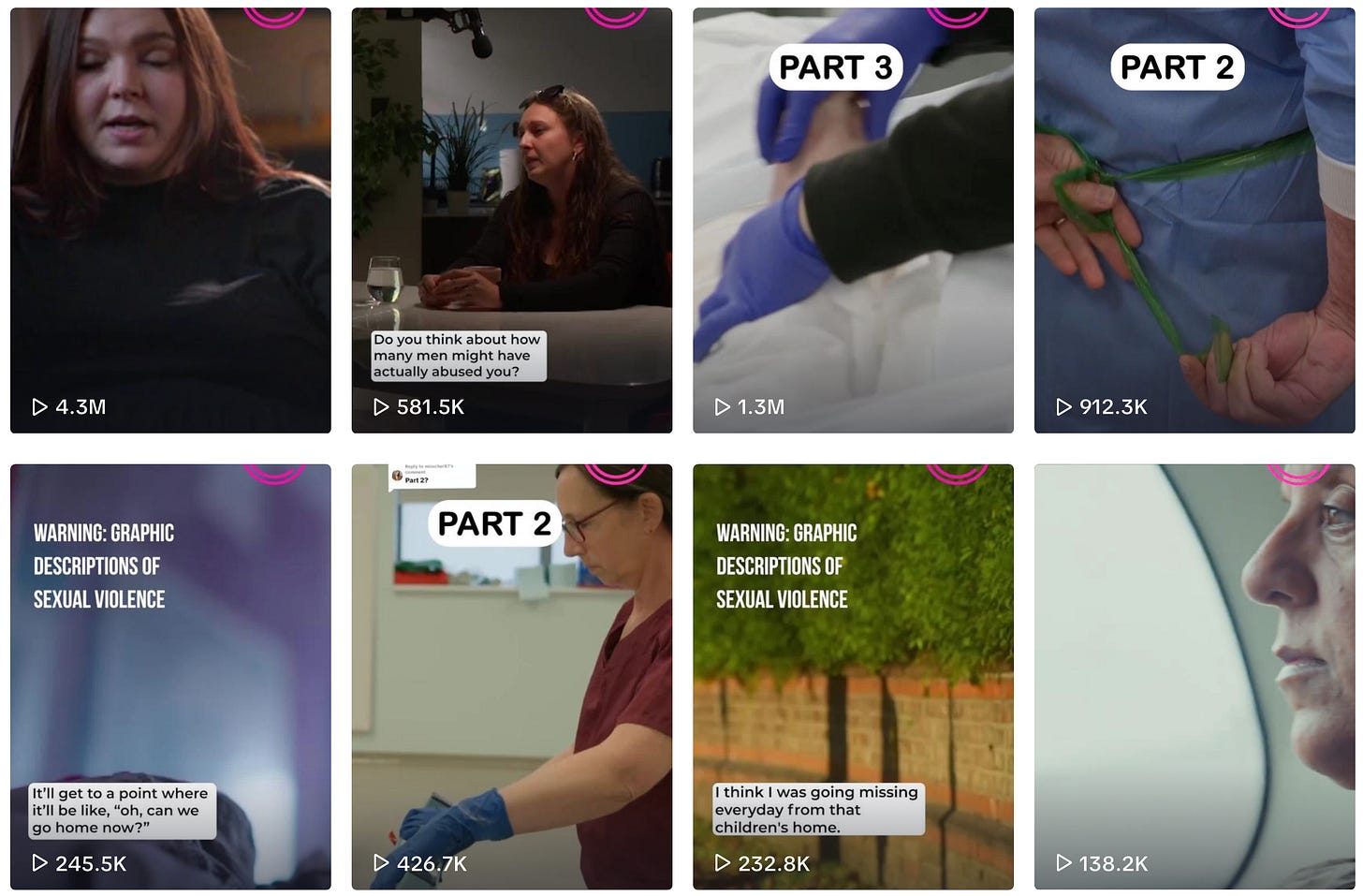

The YouTube channel was only created in January, and the three films uploaded in the last couple of days, and the company has also been uploading shorts with some really tasteful branding using their company logo, although none of these yet have really taken off. On TikTok in contrast, they have 29k followers and their videos there are getting a lot more views:

In less than 24 hours, the trio of films on their YouTube channel have significantly increased, as have their followers and total number of views. As an aside, the number of views below demonstrates how the titling of shows works differently online compared to linear TV. The two videos with clear unambiguous titles (Britain’s Sex Gangs and Hunt for Britain’s Sex Gangs) have had significant traffic increases, while the one on the same subject with with a more opaque title (Edge of the City) hasn’t increased anywhere near as much.

This is a great example of a production company using its brand, subject matter expertise and social reach to start building a global audience for its storytelling.

My recommended publications

I often get asked who I read and what I follow beyond the usual trade press, so I thought in this week’s post I’d include some of my favourites right here on Substack.

The reason for focussing solely on this platform is because as well as being a place to enable people to send out email newsletters, it also is a social network (which doesn’t require you to have a publication). And while you may not want another social platform in your life, if I can tempt you to join it is because it is home to a growing global TV and film production community, and feels like Twitter back in the heady days of the late 2000s (that is the sound of me sighing, nostalgically).

- my number 1 publication. He is so distinctive, with a wealth of knowledge backed up by hard data that he’s being cultivating for at least six years now if not longer. A little US-centric at times, but essential reading for anyone interested in data-based insights that often confound your instincts of what is a hit and what isn’t. And to be massively self-indulgent, last week reposted something I wrote on LinkedIn, so officially I can die happy now. - there are industry news aggregators, and then there’s Steven Hindes’ Further & Better. This is by far the absolute best daily pull together of news across the world’s TV, film and creator market. - if you want to know about the kids, streaming and content markets, then it is essential to read Emily. Even if you aren’t working in kids, it is worth keeping up with what happens in this space, as the kids market is often the canary in the coalmine for the rest of the media sector. - producer of over 70 films as well as previous co-head of movies at Amazon Studios; Ted Hope’s Hope for Film is a glorious read for anyone interested in the future of the medium and independent film making. It doesn’t shirk from the challenges, but remains an optimistic non-cynical read on how the industry and art form can survive and thrive into the future. - Graham Lovelace’s publication is excellent for understanding the policy challenges around the future of generative AI, especially for IP holders and existing industries. - what and the Ankler team have built is awe-inspiring. There are a whole stable of excellent journalists and specialists underneath the umbrella and they do a great job of covering the full breadth of the TV, film and content creation industries. My own favourites are ESG listed above, plus on the creator economy, on TV, and ’s daily roundup of Hollywood shenanigans which usually has at least one guaranteed guffaw in each post. Richard’s own writing is typically highly amusing, insightful and a repeated shot in the arm for creatives and show business types. - this is a fantastic new US based publication ploughing a similar part of the market to - on the hunt for all the new opportunities for TV and film creatives in our upturned world. - I love Doug Shapiro’s writing, where he consistently shares his big, deep and quite challenging thoughts on the future of the media. He isn’t showy but serious considered, and specialises in the large, broad and longer term issues, rather than anything particular tactical or temporary. - his newsletter is a fun fresh take with an Australian slant on TV and film. - Will Harrison’s publication is fairly new, but shows deep experience of working with IP-based content, products and experiences. If you want to understand how the dark arts of franchise management works, then this is insightful and hugely distinctive. - Julia Alexander is one of my all time favourite thinkers and writers about technology, the media and changing audience behaviours. She’s now headed to Puck.News, so her Substack is less active, however anything she chooses to publish there (and everything at Puck) is worth reading in my view. - Marion’s was one of the first publications I followed when joining Substack, and it (along with her various activities with ) are a valuable and reliable source of insights and information. She also gets access to great minds such as this week’s interview with Alan Wolk, who has been one of the key analysts into the future of TV going back decades.That’s it for this week - drop a comment below if anything sparked a thought!

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

YES. There is a powerful psychological barrier.

When you have spent years making high budgeted projects for streamers/theaters/etc. you WILL face internal and external questions of: wait… you’re making YouTube videos? Have you failed? Can’t you get your projects funded/commissioned anymore?

Im building a direct to consumer business right now. 90% the people I talk to about this plan look at me like I’ve lost it. The other 10% want to join me.

Also, there’s a tendency in legacy media to not believe a project is real until there’s a press release. And there won’t be a press release for your YouTube series even if it gets 10x the viewership it would have on Netflix.

Lastly, it’s a psychological barrier in that it requires a shift in thinking. We (legacy media producers) are used to planning and budgeting based on raising funding and getting commissions. This gives us the resources we think we need to make something, and the psychological permission to go do it. Now, instead of self-starting to develop, we need to self-start to MAKE and DISTRUBUTE and MARKET. That takes a shift in thinking, a shift in financial planning, and a shift in behavior.

I’m done ranting, I have to go make something.

P.S. I’ve really been enjoying your posts about producers and YouTube. Please keep them coming!