'A bottomless pit of plagiarism': Disney & Universal sue gen AI company Midjourney

Plus what next after the WBD split; MLB partners with creator company Jomboy; more on microdramas; Mubi lands $100m investment; and Apple's new TV backend revealed.

This is one of those weeks where the saying ‘when it rains it pours’ comes to mind. There has been so much activity that has strategic importance for TV and film producers, it has been more than a little tricky to put it all into an email that doesn’t become a thesis. This week includes:

AI and copyright heats up: Midjourney sued for copyright infringement by Disney & Universal

Warner Bros. Discovery splits

Major League Baseball buys into creator-owned media network Jomboy

Microdramas, self-financing indie TV and Channel 4 releases its first digital drama commission

Mubi receives $100m investment from Sequoia Capital

Apple’s new TV backend revealed

Tellycast award winners.

If you find this helpful, please do share with your colleagues:

Disney and Universal sues Midjourney, adding to the pile of gen AI copyright cases

The news this week that Disney and Universal are suing gen AI company Midjourney is further evidence of how seriously IP owners are treating what they view as theft by various AI companies:

BBC: Disney and Universal this week sued Midjourney, saying the AI company ‘is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism’.

As well as this new case, there are several others underway:

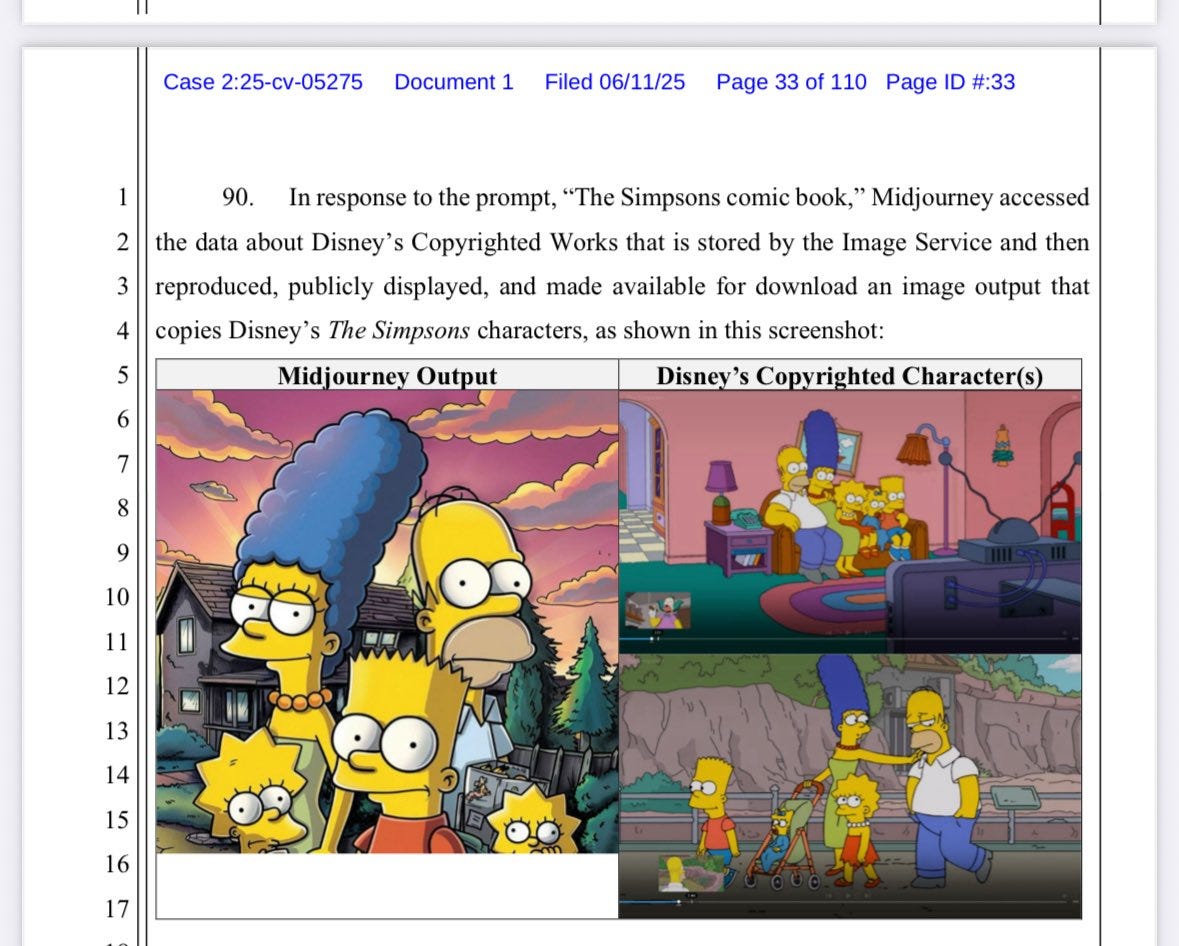

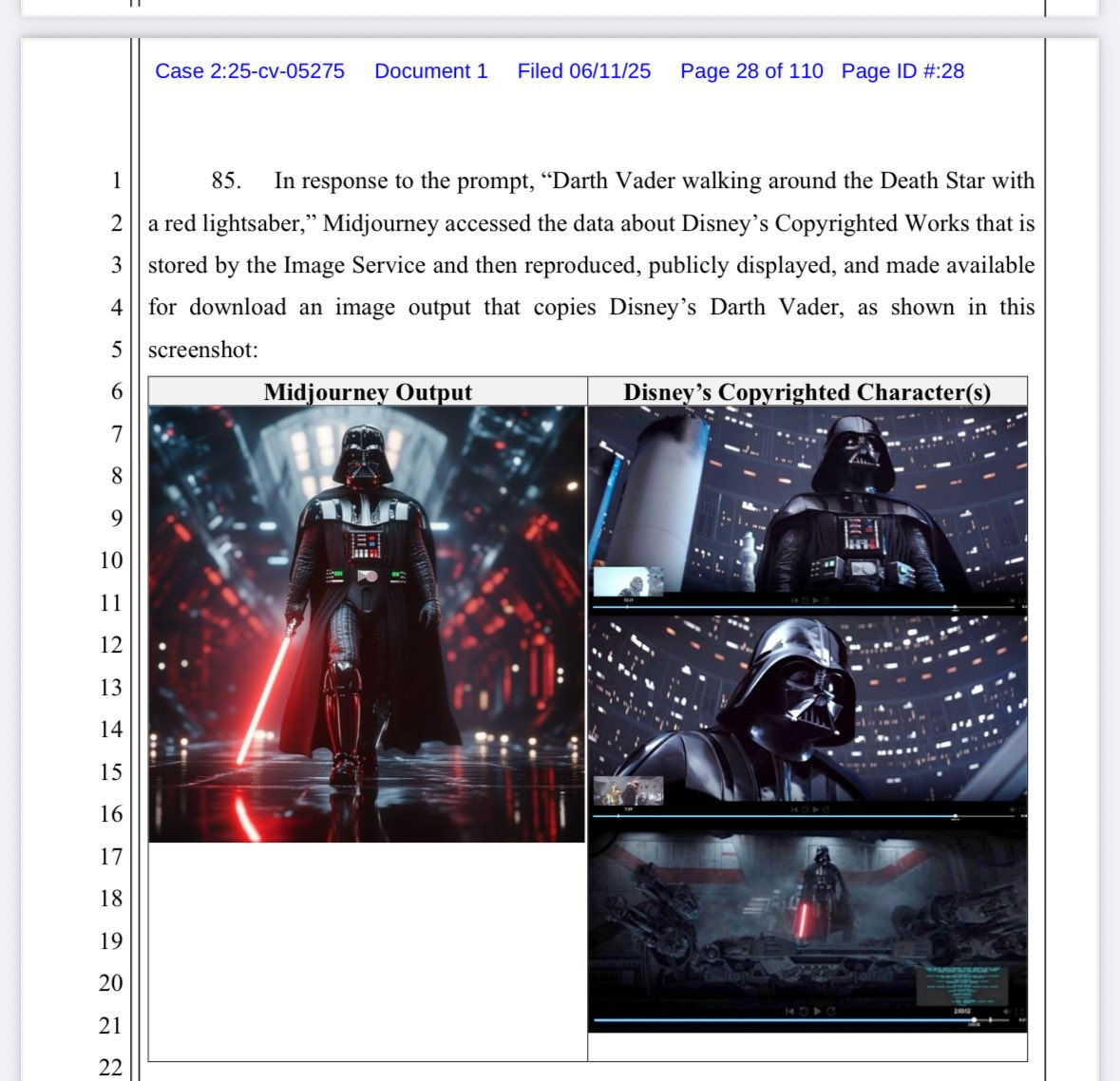

The Midjourney lawsuit is probably the most relevant to the TV & film production sector, and the filing includes many examples which Disney and Universal believe illustrate their IP is being used without permission. Here is one screen grab in the court filing:

AI companies have often argued they are protected by the USA’s ‘fair use’ rules; so in broad terms, copyrighted works can be used in certain circumstances which involves the new work being ‘transformative’ or adding new meaning. (I’ve written previously how the US concept of fair use differs to similar laws in other territories, and also how users’ understanding of these defences can be fairly expansive when compared to a UK copyright lawyer’s more informed and narrower interpretation of what is reasonable under the law).

It is not possible to predict the outcome of these types of cases, however in this Wired article, Matthew Sag, a professor of law and artificial intelligence at Emory University, outlines why he believes Midjourney will have a hard time making a fair use defence:

It’s going to be very difficult for a court or a jury to accept that it is transformative to take 1,000 pictures of Darth Vader and use them to produce even more pictures of Darth Vader.

Back in January 2024, Gary Marcus and Reid Southern shared how they believed Midjourney could have a plagiarism problem, and many of their examples appear to have been cited in the court filing by Disney and Universal.

Gary Marcus wrote yesterday on X that ‘generative AI is uniquely vulnerable’, going on to say:

Unlike other earlier AI-based industries such as search and recommendation engines, the whole field of generative AI is almost entirely dependent on downloading and training on vast troves of intellectual property

Most of the property has not been properly licenced

Because basically all the big players are doing the same kinds of things, a single legal case could have vast ripple effects throughout the entire industry

If a significant court decides that the training-without-licensing in systems that have a tendency to plagiarise is illegal, every company will suddenly be in jeopardy

The Disney/Universal suit could easily set such a precedent.

And meanwhile, Press Gazette had a story about how some YouTube channels are using AI to rip news stories from behind publisher paywalls to turn them into faceless videos to generate advertising revenue on the platform:

The Press Gazette quotes a journalist who had their story taken in this manner:

Google are handling stolen goods in plain sight and governments must find the way to hold them responsible. In the real world selling on stolen stuff is as serious as the criminal who stole it in the first place. Why should it be different in the virtual world?

Just this week the BFI released a new report on the use of generative AI tech in the screen sector, which stated that the sources of AI training data include scripts from more than 130,000 films and TV shows, YouTube videos, and databases of pirated books:

This situation with copyright makes it exceptionally difficult for TV producers to experiment with generative AI, right at a time when production companies need to be able to innovate without having to worry about being sued in the future for copyright infringement. The ideal scenario is for TV and film producers to have the option of being able to make shows and films that use AI generated footage, safe in the knowledge that the material hasn’t been created using uncleared IP, and in turn that they own the copyright of what is produced. Only then can they be confident in selling these shows to broadcasters and streamers, and not face any risk around a future copyright infringement claim. The longer this situation exists that they can’t be sure the generative AI tools are safe to use, the longer TV and film producers are being held back from exploring this new opportunity.

All the while, the internet is becoming awash with AI generated material by creators and individuals, much of which has been produced via LLMs that appear to be trained on copyrighted material. So while IP holders are unlikely to sue these individual creators for copyright infringement (but not impossible they could sue certain high profile creators), they are suing the AI companies who own the LLMs the creators are using to produce the content.

This whole situation prompts a sense of déjà vu, as previous waves of disruptive technologies also had issues with copyright licensing, and often this was followed by suggestions that being unhappy about potential IP infringement was a form of luddism. In most of these cases, commercial deals and agreements were struck, partly due to the potential threat of legal action, but also because the disruptors themselves perhaps realised that not coming to an agreement on copyright was actually holding their companies back - and indeed, the commercial deals would (and did) enable their companies to grow. Think of how YouTube developed its content ID system to police copyright and came to agreements with music labels, studios and other rights holders. Or how Napster and Limewire slid away while Spotify - who did the commercial deals - went on to thrive. When there are reports of music labels in licensing talks with AI music generators, perhaps we are starting to see the same pattern emerging.

This is all happening at the same time Apple researchers released somewhat of a bombshell paper that suggests the AI industry has overhyped the ability of the technology:

The illusion of thinking... frontier [reasoning models] face a complete accuracy collapse beyond certain complexities."

There has been quite a storm online in response to this Apple paper - with this six year old clip from HBO’s Silicon Valley doing the rounds as it was rather prescient…

Meanwhile, last night the deadlock in parliament ended and the UK data act will pass into law, without the amendments IP owners and the creative industries heavily lobbied the government for. Instead, the government has offered joint industry working parties on transparency, licensing and technical standards, as well reports into economic impact assessments.

We are in the early days of a major disruption, and it is nigh on impossible to predict how this technology will develop, how these cases will resolve themselves, where the commercial models emerge from and how tech companies and IP holders will come to an agreement on the best way forward for copyright usage.

Although precedence suggests that global events - such as Disney/Universal lawsuit against Midjourney - may trigger the very commercial deals around generative AI that rights holders are looking for, which in turn could unlock the opportunity for producers to confidently explore new creative and commercial models.

Warner Bros. Discovery: when one become two…

Finally, after much speculation, the deed has been done and Warner Bros. Discovery will become two separate companies, with the split to be concluded in 2026. One company will be for streaming and studios, and the second will be home for the profit-making but declining cable TV channels. The debt split isn’t equal, suggested to be around $27bn going to the cable TV company, and the remaining $7bn going to streaming and studios. The idea being that the cable TV networks company will use its cash flows to service the debt.

I’m not going to rehash the analysis on this decision, as there have been many excellent articles, podcasts and posts on this already - I’ve included a digest below. However, just a few pointers that I thought were of interest in this announcement, why it matters, and also what are some things to look for in the future. And yes, I get into wild speculation on future M&As…

Firstly, the split itself. It is positioned as studios and streaming versus old cable TV channels. However, as many analysts noted when the rebrand of Max as HBO Max was announced, it is closer to a split back into the Warner Bros. and Discovery parts of premium scripted/cinematic versus reality and factual content. While the streamer Max was originally positioned as an everything destination with both HBO and Discovery/TLC/HGTV content all together, the detail here confirms what many have said, which is the single streamer has not worked, and HBO Max will really be HBO and the Warner Bros’ Studios catalogue. Meanwhile, the Discovery TV content will sit on the Discovery+ streamer that is now in the WBD Global Networks company below. CNN is sitting in the TV cable company, and the Olympics logo appears on both slides below.

Secondly, how long will either of these companies stay as they are? As Alex Sherman of CNBC said on X:

WBD CFO Gunnar Wiedenfels twice stresses that new consolidation (with another company, that is) can happen immediately, without a 2-year delay, after the split. If that's not a signal, I don't know what is!

All eyes at that point look to Versant, the Comcast spin-off company of NBCUniversal’s cable TV channels. However, as The Hollywood Reporter noted, Versant is expected to have ‘minimal debt’, so it can be an opportunistic acquirer. Bob Iger has said Disney isn’t spinning off their channels in a similar fashion (despite previously hinting this could be a possibility). Indeed, he told CNBC that he believes Disney’s linear TV business paired with a streamer gives his company an advantage over its rivals (as reported in Axios). Maybe for now, but is it beyond the realm of possibility to image a single enormous cable TV company with all of the profitable yet-declining TV channels within it?

As for HBO: how long will this remain a standalone company? While the HBO Max streamer may do better with this clearer proposition without the muddying of the Discovery reality content, is the catalogue so golden it can sustain a single streamer at this size? Or will it, as long has been expected, be purchased or merged with something else? And will that involve the studios too?

One little mentioned indicator that perhaps these two new companies are somewhat temporary in nature is that WBD’s two streamers (HBO Max and Discovery+) will now live in two different companies, however they both sit on the same underlying tech stack (Discovery+ migrated to the Max tech stack as announced earlier this year). While this creates a level of efficiency, having two separate companies sharing a platform in this manner could be tricky to manage in the longer term. Put simply, there is a risk that one company’s wishlist for new features and functionality gets prioritised over the other company’s. Who knows, the needs of HBO Max and Discovery+ might be aligned for ever more, but it isn’t uncommon within organisations for conflicting and competing demands to be made on a single platform and development team. All this could be exacerbated by the two streamers being in different companies, and while they can try to mitigate these conflicts, over time they can become even more pronounced.

Thirdly, who might buy either company? Considering the previous corporate history of Warner Bros. and Discovery, then a telco might be interested. This timeline from Axios on the history of Warner Bros. mergers and acquisitions is rather arresting.

Looking further a field from telcos, it has been much repeated that Apple would be a natural fit for the HBO and Studios brand, as they don’t have a large streaming catalogue to supplement their originals and pay per view/download to own/rent titles.

I wrote previously how the coming bigger streaming battle between Netflix and YouTube makes things a lot more tricky for Netflix.

If this is the case (and yes, this is now much further into the realm of idle speculation), then one way for Netflix to see off the Google platform could be via a merger of some sort with a larger consumer tech company. If this is on the cards, would the likes of Apple prefer to hold off for that bigger prize rather than buy HBO Max?

Equally, there is another contender that isn’t mentioned very often, and that is Microsoft. Rather savvily, Microsoft got out of the TV streaming wars back in 2014 when they shut Xbox Entertainment Studios, saying at the time what they do is productivity and their entertainment play is Xbox itself and not original TV & film programming. Well, Microsoft is now the world’s most valuable company, at £2.26 trillion (Apple is currently £2.2 trillion). As well as productivity tools, they also have around 20% of the cloud computing market, where they compete with Amazon Web Services. Would it make sense for Microsoft to reconsider its stance and get into the entertainment and media space via the acquisition of Warner Bros. streaming and studios (not forgetting Warner Bros Games has multiple AAA games released on Xbox)? And if there is even a slim chance of that being a possibility, then why not Netflix itself?

At this point of speculative meandering, it is probably worth including the dollar amounts we are talking about and the size of acquisitions these companies have done previously.

The two WBD companies don’t have valuations yet, but the current combined WBD company was recently valued at $23.5bn, which is 60% down since 2022.

In terms of previous acquisitions, the biggest Microsoft has ever done was the $68.7bn deal of Activision Blizzard. And the biggest Apple has ever done was $3bn for Beats back in 2014. As for Netflix, its current valuation is $521bn.

Hollywood Reporter: RichCo vs. PoorCo: Not All Spinoffs Are Created Equal

Business Insider: Warner Bros. Discovery doesn't want its cable channels like CNN anymore. Who does?

Bloomberg: Warner Bros. to Split Into Streaming, Cable TV Companies

Variety: Disney Closes Hulu Deal With Comcast, Paying Billions Less Than NBCU Was Seeking

MLB buys into creator-owned media network

Major League Baseball has struck a strategic partnership deal with

, the irreverent creator network which includes 2.1m subscribers on YouTube (1.5bn views), 985k on Instagram, 668k on TikTok as well as podcasts such as Talkin’ Baseball and Talkin’ Yanks about the New York Yankees.Jomboy Media also has Warehouse Games - 331k subscribers and 181m views on YouTube - a baseball-cricket hybrid indoor league ‘where backyard and back-alley sports meets high-end production’. This was picked up by Bally Sports in 2024 to run on its channels and app.

I thought I’d use Jomboy to draw your attention to another characteristic of the creator space that might not be immediately obvious: how many creators have second, third or even more channels as well as their main channel on YouTube. MrBeast has been doing this for a while, where in addition to his main channel, he has MrBeast2, Beast Gaming, Beast Reacts and Beast Philanthropy. Or YouTube’s resident librarian Jack Edwards has his main channel and then his second channel. Creators do this for a variety of reasons, such as building more specific niches or enabling alternative conversations with different audiences. It can also act as a potential hedge against their main account being suspended.

And so Jomboy has second channel too, called MoreJomboy where Jimmy O’Brien (co-founder of Jomboy) and others share what it is like to build a media company via a podcast called The Monday Meeting (remembering a key feature of the creator economy is the level to which individual creators externalise their experiences in building their channels, audiences and companies).

Below is Jimmy explaining the MLB deal, and also how he’s grown his company from a hobby to 60+ employees.

Microdramas, self financing indie TV and Channel 4 releases its first digital drama commission

This week, there have been some further updates or deeper dives into some of the online scripted trends I’ve covered previously:

More on the world of microdramas

I’ve written before about the trend of scandal-laden microdrama apps, which are growing in popularity:

has done a deep dive into this space which is well worth your time, on both the numbers as well as the production costs and opportunities around this trend for TV and film producers.They include an interview with Kasey Esser, a ‘microdrama careerist’ who has starred in 42 projects (playing roles such as a billionaire and a vampire bodyguard), and his typical month’s income now ranges from $30,000 to $40,000.

The Ankler piece also notes that this type of content may create opportunities for brands to reach certain markets such as Africa and South East Asia. Indeed, it says that Spanish language media giant TelevisaUnivision has already stepped into this space:

And, just this week

has written about microdramas in India:Self-financing indie TV

I wrote a few times last year about Mark Duplass, and how he (and his brother) are trying to adapt the indie film financing model for TV. For example:

This week, Vulture had a great interview with him to see how he is getting on in his endeavour, and it is full of lots of interesting insights as he tries to navigate this world.

The piece suggests that while the indie TV model last year seemed a natural progression for TV and streamers, it hasn’t matured in the way it was predicted. Even so, Mark and his brother continue down this path which has its own twists and turns, based on the principle:

My whole business model has been based on: “Companies normally pay X for things. They’re thrilled that Duplass Brothers can deliver it to them for 0.5x. I can make it for 0.25x and everybody wins.”

Another interesting point is he is distributing his latest series via Kinema, which is one of several distribution platforms that exist to allow filmmakers and producers to directly rent to audiences while retaining their rights (another example for documentaries is jolt.film). They are also putting it on crowdfunding platform Seed&Spark.

Channel 4 releases its first digital original drama

This week Channel 4 released Beth, its first digital original drama. It has been published simultaneously on Channel 4’s All4 streaming service as well as YouTube.

Read more about online scripted drama trends as well as examples from the past 20 years:

Sequoia Capital invests $100m in Mubi

Recently it was announced that arthouse cinema company Mubi has received a significant investment from Sequoia (the long-standing VC firm behind so many tech companies from YouTube, Instagram, Reddit, to Google, Apple and PayPal).

Mubi is one of the most interesting companies out there in this new space: not just a streamer, they are a theatrical distribution and production company with a membership programme, live events and a print publication. All focussed on attracting and retaining a global tribe of like-minded souls: “…film lovers searching, lost or adrift in an overwhelming sea of content”. Or as this Variety profile on founder Efe Cakarel describes his initial vision: “…frustrated, he imagined a website from which indie movie lovers like himself could stream the best films from international auteurs.”

As this Crunchbase article demonstrates, the investment in Mubi comes after a ‘sluggish period for venture in the media space’ - and what media investment there has been has been is in AI media generation rather than human-made creative content or streaming platforms.

Another notable dimension to Mubi, which surely must have also been appealing to investors, is that the company has built their own infrastructure for their streaming platform. As Efe Cakarel said in the Variety profile:

“We built our own content delivery network, our own encoding tool chains and our own streaming services,” he says. “But we estimate that it costs us 70% less for our infrastructure than those who rely on other platforms.”

When thinking about all the streamers out there targeting specific niche audiences, it is worth keeping in the back of your mind that the ability to scale audiences (and profitability) often comes from a company’s technical capabilities and not just what audiences see when using the product such as the design, user experience and content.

Apple’s new TV backend revealed

An insightful read from

in on Apple TV’s new points system to reward producers of hit shows. This will replace the previous iteration, which was seen as leaning too much towards rewarding everyone rather than only the shows that really perform. The piece quotes a lawyer who suggests from Apple’s perspective:We’re happy to pay for hits. We don’t want to pay for stinkers anymore.

Apple continues to be one to watch over the coming years. They have a number of high quality hit shows - Slow Horses, Ted Lasso, The Morning Show - and while they don’t release specific subscription numbers it is notable how their titles don’t appear in the top 10 Nielsen streaming lists in the US. As mentioned previously, the service lacks a high volume TV & film catalogue as part of the subscription package, and therefore having spent a reported $5bn per year on originals, there are various people wondering how their strategy will shake out over the coming months and years.

Tellycast award winners

The brand new Tellycast digital video awards were held last week, and it is worth browsing the winners listed here on their website and below is a recap and highlights video of the event.

Find out more about me and the purpose of this newsletter, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.