The doom loops: cable TV subs, streaming numbers and YouTubeTV drops subscribers for the first time

One of the purposes of this Substack is to keep track of the big trends in the US TV and film industries, knowing that these sniffles (or ahem, full blown influenza) will have an impact on the UK market, either commissioning, distribution or production. Or more likely, all three.

In the last weeks there have been several datapoints which have brought into focus the direction of travel for some of the big beasts in the US TV market - what analysts MoffettNathanson dubbed the twin ‘doom loops’. Or as the above Castlemaine XXXX ad said, “it’s gonna be real bad, Bill”.

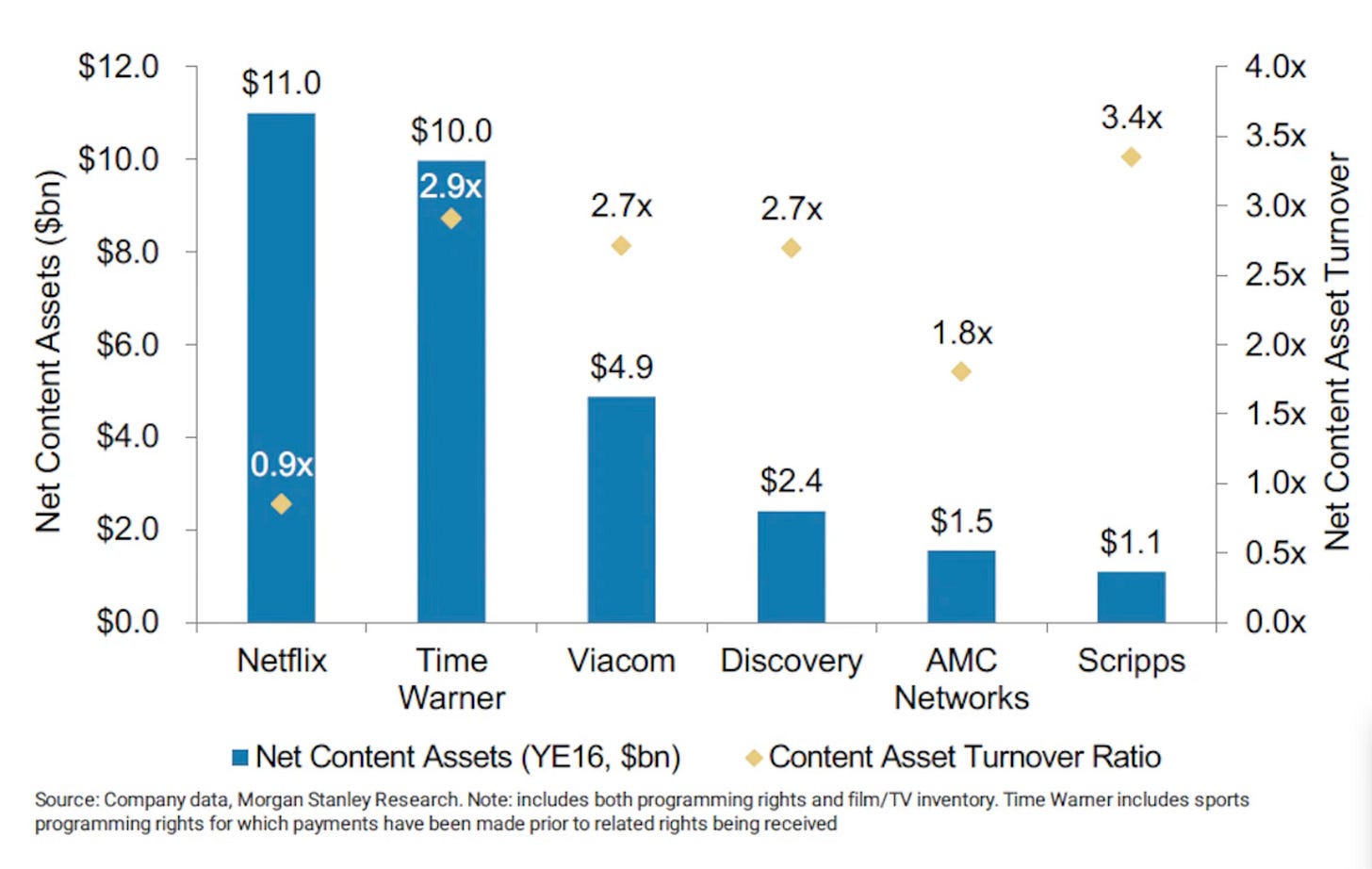

Sometimes it has hard to understand how different the cable linear model is to the streaming on demand approach in terms revenues and how that relates to content commissioning. The below graph from 2017 shows the different strategies of Netflix and the cable channels. While Netflix at this point was firmly ramping up its content spend to build a huge programming library, it is worth noting how effective the linear cable model was for Discovery, AMC Networks and Scripps in delivering revenues from their assets.

US cable TV performance

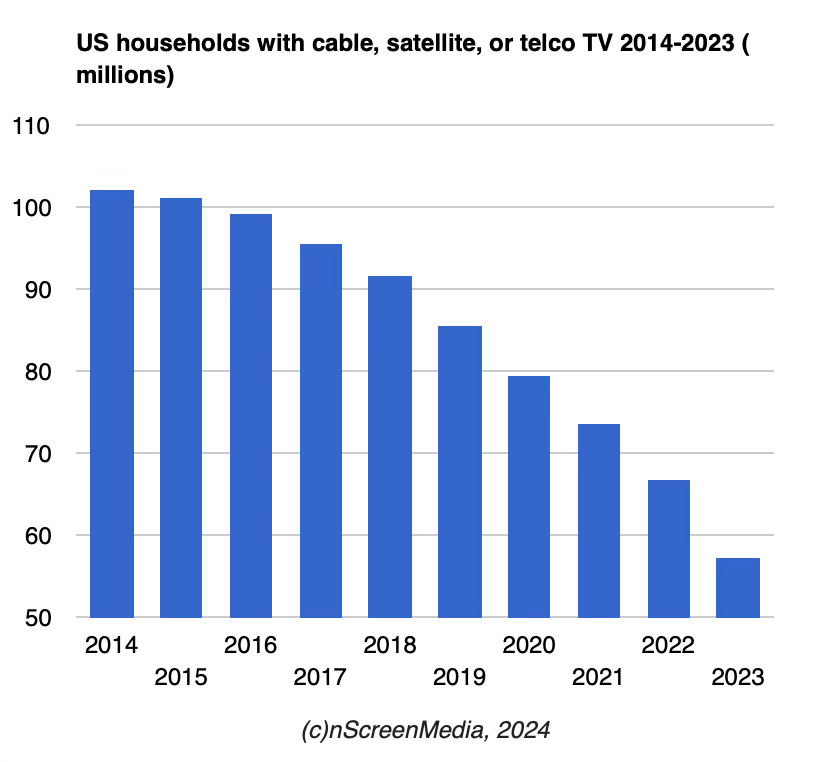

The decline in cable subscriptions and the cord-cutting trend has been such a long running theme in the US market over the past 20 years that it has almost become background white noise.

However recent subscriber and streaming numbers illustrate how future business models are proving somewhat elusive in replacing the lost earnings from the highly lucrative linear cable market.

Subscriber numbers

There was a 6.9% decline of cable TV subscribers in the US in the last quarter - the worst quarter in history - according to industry analysts MoffettNathanson’s cord cutting monitor report.

In real numbers, in Q1 2024 there were 57m households with a cable TV package, compared to 102m back in 2014.

The industry previously had the belief that although overall subscribers would go down it would do so over a very long time, and that enough younger people becoming homeowners and taking out subscriptions as they matured would slow the flow of water from the leaky bucket, if not for decades but at least long enough to find new revenue streams to replace the old cable TV subscription model.

It has long been the view that this was wishful thinking and that this trend didn’t happened to anywhere near the degree it was hoped, and therefore the subscriber base is simply shrinking and those remaining are ageing. Although some have observed that cable/satellite TV in the US remains important for those in rural areas with poor internet connections - perhaps Starlink et al might change that in the future too.

Streaming numbers

For all of these companies, the hope was for streaming subscriptions and/or ad money to replace cable TV subscription income. However even here, there are no real bright spots.

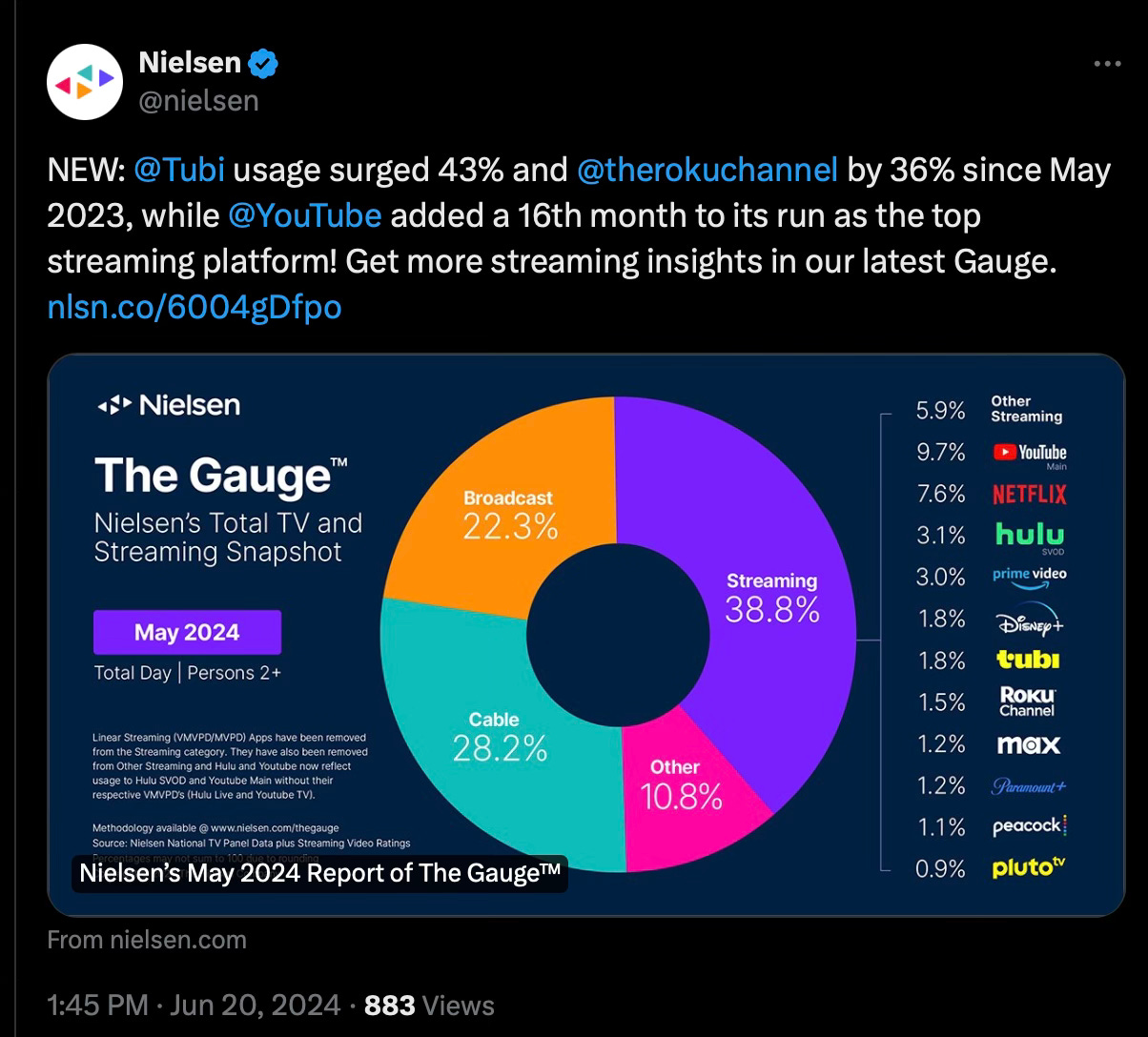

I wrote last week about the last streaming audience figures; how small the numbers are for the traditional TV subscription services in the US (Disney+, Max, Paramount+ and Peacock) and how the free advertising platforms are increasing their share - YouTube obviously but also Tubi.

There was a hope that vMPVD services like YouTubeTV would create a new vehicle to build replacement income for the lost traditional cable subscriptions. YouTubeTV costs $72 per month - a high price point, and not far off what cable costs - to watch a mix of premium sports and bundled channels, but with no contract and not set up costs. So in theory, it (and other services like it such as Sling and Fubo) offer a potential life raft for cable TV operators to leap onto replacing their traditional subscription base.

However, YouTubeTV for the first time saw a decline in subscriptions this month of around 150,000, largely driven by the end of the sports season in the US. While this ability to chop and change what you pay for is appealing to users, it makes it hugely challenging for traditional TV operators to plan and run their operations and make creative & commercial decisions on what programming they want beyond sports.

Taken together, these moments in the last weeks are showing the direction of travel over the coming months and years. Shows on cable networks in 2024 are getting a quarter of the audiences they were 10-15 years ago and these numbers are simply not (yet?) being made up via streaming services - either on demand services (such as Disney+ or Max) or cable-like services but without the contract (like YouTubeTV).

Add to this, the scale of the technological advantage of competitors like YouTube and Netflix means traditional TV companies need seriously deep pockets to invest in their distribution infrastructure and tech stack. However for companies like WBD with debts reportedly of $43bn (in 2022), makes it hard to invest in technology at anywhere near the level required to compete. Perhaps time for a radical new strategy - creating a single streaming platform perhaps as previously floated by David Zaslav, or binning their own streaming platforms and instead use a third party like YouTube.

‘A bloodbath’: US trends for TV and streaming platforms

US media analyst Michael Nathanson (of MoffettNathanson, responsible for the above doom loops graphic and several other tables/links in this post) was interviewed at length this week. A few notable points included:

Amazon moving into the video ad market has caused and will continue to cause a huge level of disruption to linear TV advertising as well as other streaming competitors with poorer data and smaller audiences such as Pluto

TV ads fell double digits - was 32% of the market in 2019, down to 21% in 2024 - first time this has happened in a non-recession year

Current revenues at broadcasters for both streaming and linear are down 40% on what they had forecast back in 2018

YouTube on connected TVs is bigger than Netflix by some margin

In two years, YouTubeTV will be the biggest paid TV provider with 10m subs

The broadcasters’ streaming services together are not as efficient or delivering the profitability of Netflix - together they made $5bn in losses while Netflix made $10bn in profit in the same period

Consolidation will happen in the next few years to have a chance to create economies of scale - Disney and Hulu+ obviously, and then something perhaps with HBO, Max, Peacock and Paramount

Advertising will be the primary source of revenue for streaming in the future - while subscriptions will remain, it will be ads that are the main income stream

There is a lot of hype around FAST channels and they now need to start making money which might prove challenging for the smaller players as there is too much ad capacity and CPMs are too low.

The whole thing is an insightful and excellent analysis of the state of play, and the big takeaway for the US cable market and the wider ad-funded TV market is that there is an awful lot more to come in terms of change and disruption around where ad money flows.

On the future of advertising and subscription TV businesses, this newsletter from Lucas Shaw is also well worth reading. He summarises the challenges for Netflix to carve out advertising revenues, which is that it simply isn’t big enough - it just scrapes into the top 10 video advertising players, far behind YouTube, Disney, Paramount, WBD, Roku and others. He compares Amazon’s approach - turning advertising on for all users, where you have to pay for an ad-free experience, charging advertisers an undercut price point - with Netflix, where users have to opt-in to the ad option so the user base is smaller in comparison. This means that Amazon is already nearly three times larger in terms of ad sales than Netflix ($1.1bn to $0.4bn). Fundamentally, he notes that Netflix is in a tricky situation with audiences in terms of an advertising offering, as up until now it has sold itself as TV without ads so introducing ads runs the risk of irritating their subscriber base. In comparison, its competitors such as Amazon have an easier time running ads as their users don’t associate their brand as being incompatible with advertising in the same way.

Both of these pieces are US in focussed, but the growth in streaming video platforms taking ad money will naturally have a consequence for ad-funded broadcasting and streaming in the UK - worth noting Channel 4’s announcement this week that their streaming performance has outpaced the market in the first half of 2024.

YouTube the one to continue watching

Along with Tubi, YouTube is the platform that TV should be talking about an awful lot more but hasn’t been. Thankfully, Alex Sherman at CNBC has done a big piece on the company, helping to shed some light on its extraordinary position in the market and what it means for the linear and streaming TV. In the above graphic from Nielsen, YouTube (main, excluding the YouTubeTV service) makes up nearly 10% of all viewing in the US.

The platform has long caused head-scratching for how TV businesses should respond to its dominance - as a friend, a foe, or in a separate entertainment category altogether. As Alex Sherman notes:

‘Some media executives see YouTube as a companion platform to subscription streaming services and cable TV - an unwieldy behemoth of non-narrative, creator-led content with a social media slant that doesn’t really fit the New York-Hollywood nexus of professional media. Others- even at times the same executives - view YouTube as an existential threat to the entertainment industry, stealing viewership from subscription streaming services and, with it, the cultural center of American youth’.

How popular YouTube is with kids and youth is hard to overestimate. For well over a decade, more than 85% of kids are using YouTube, and the second most popular website is 35 percentage points behind (Google, on 50%). So the concept of YouTube as cultural centre for kids and youth is an important point especially as they age and become adults and what that means for their expectations and behaviours.

However, for all its scale, the YouTube business model is not one that can replace the current TV linear model as a mechanism to fund the volume of relatively expensive to produce scripted and unscripted programming and the established funnel for what it takes to deliver hits (so how many ideas go to development, and then from that the number taken forward to paid development, to full green light, the then an acceptable cancel rate versus recommission). While attention goes to YouTube channels such as Cocomelon which has amassed 182bn views, the reality is that YouTube’s advertising CPM (cost per mille - cost per 1,000 views) is around $13 - 15. Although premium content can charge higher rates, and these CPMs don’t include subscriptions, merchandise, or sponsorship revenues, the earnings for 1,000,000 views ranges from $1200 - $6000. So even after YouTube’s 45% cut, it is hard to see how this model ever could replace linear TV commissioning budgets.