How to tackle YouTube if you’re a TV production company

The ways in which TV production companies can build and manage a YouTube channel.

Last week, I wrote about how and why production companies should and could build direct relationships with audiences. This week, I’ve focussed on YouTube, and what specific issues TV producers might consider if they want to get to grips with it as a platform.

A recap for why YouTube really matters: The platform is coming to eat TV’s lunch. It is a video platform. TV is the ultimate audio visual storytelling machine. Ergo, it is the most obvious and natural platform for TV producers to be making hay. I quoted Evan Shapiro last week, where he said:

YouTube is the biggest TV channel in America. Despite all the data in front of everyone’s faces, it doesn’t seem to have sunken in or changed the strategies of any of traditional media. Dumbfounding.

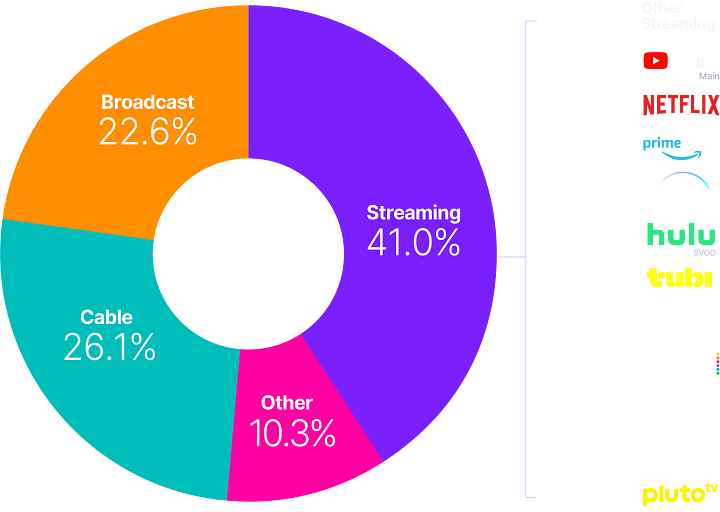

To illustrate this point, below is Nielsen’s September US daily viewing report, which shows YouTube with 10.6% share. Plus Ofcom’s report from 2023 on video viewing behaviour, where video sharing platforms (which includes YouTube) makes up 17% of all UK video viewing.

Before diving in: YouTube is a whole ecosystem which is as complex, varied and challenging as broadcast TV. This post is a tiny tip of the iceberg intended to encourage production companies to shift YouTube up their to do lists (or those that have started on the platform, get to the next level). However, this isn’t a short term or peripheral initiative that once completed can be forgotten; instead YouTube is an ongoing activity that needs to be embedded into companies’ operations.

Also, this post isn’t intended to duplicate the acre of information out there already - articles and how to guides, white papers, videos and courses. Rather, the intention is to draw your attention to some of the specifics that can impact TV production companies.

YouTube and TV thus far

YouTube has been around for 19 years, and broadly speaking, the TV industry has engaged with the platform in two ways: marketing and monetisation. Marketing as a means to get users to watch shows either on TV or a streaming platform, and monetisation where ads around archive shows generate revenue.

Because of how TV works, both of these activities have largely been the responsibility of other organisations and not the producers of the shows themselves. Programme marketing is a core function of broadcasters and distributors, and when it comes to monetisation, often companies outsource that responsibility to rights management agencies, who then proactively manage the titles on YouTube as well as other platforms.

The net result of this has been a YouTube blind spot for many (most?) production companies. So much so that very few companies have presences on YouTube at all - when searching for production companies on the platform, often the only results that come up are company logo and ident videos published by this channel.

This approach has worked as long as the fundamentals of the broadcast and streaming ecosystem stayed as they were. However, now that the great-up-ending of TV is in full swing, it is increasingly unsustainable for TV production companies to not have a footprint on YouTube, nor it is helpful to not have an internal understanding of how the platform functions.

Therefore, it does seem that was then and this is now, so this post suggests a way for TV production companies to start thinking about the platform by firstly developing understanding about how YouTube works and secondly, building out a rudimentary channel on the platform. The next step is to encourage producers to consider YouTube as an original creative outlet in its own right, however this will have to wait until a later post.

Perhaps you might be thinking ‘Really?! In this market?!’. However, these recommendations aren’t suggesting replacing anything partners are doing already, nor do they require endless resource and investment (although, that might be an option for individual companies). Instead, the intention is to help normalise YouTube within TV production as a routine and understood platform, rather than something that needs to be dealt with in the future.

So, in no particular order, here are some aspects of YouTube that might not be apparent as a user, but are important for TV producers to get to grips with.

Content ID and copyright

One of YouTube’s many impressive technical feats is its Content ID system: an ever growing database of audio and video files which are checked against newly uploaded material, and the owners of anything found to be copyrighted are alerted and given the options to either track, monetise or block.

Content ID is important for production companies as uploading material that has been broadcast is likely to bump into the system fairly quickly, and it is best to avoid getting copyright strikes. Usually this involves one of the following possibilities:

Shows are claimed in content ID by an organisation with the rights to them such as a broadcaster or distributor

Content from a show has third party material in it that was cleared for broadcast but not YouTube (such as commercial music or archive footage)

A user has uploaded material from a programme either a clip or the whole episode.

For 1 & 2 above, getting clearances sorted, talking to the organisations who have claimed ownership within YouTube, and then using playlists (see below) offer a way forward.

For the third type above, it is important for companies to develop a user generated content policy on how to handle IP from shows that has been uploaded by users. To help inform a company’s position, Little Dot Studios published a report into UGC and rights in October this year.

Rights in general

For some production companies, especially those commissioned by public service broadcasters, then rights (and archive rights) are less of an issue. However for those that are more focussed on work for hire or complete buyouts, this is more tricky.

Some broadcasters, networks and streamers might not be open to discussion about YouTube even for archive titles, however others might see any effort to invest in the platform as an option for marketing and monetisation that could aid their core business via revenue sharing, cross-linking and promotional activity. The mantra don’t ask don’t get might be pertinent here.

Multi-Channel Networks

The management of TV brands on YouTube and all that this involves - rights management, content planning and publication, audience management, monitoring performance, monetisation - is where companies like All3’s Little Dot Studios and owners of large archives such as BBC Studios have succeeded by developing expertise in creating and managing their MCNs - multi-channel networks.

These MCNs are verified by YouTube, and YouTube provides the following information for rights holders and creators on how MCNs work.

By putting huge volumes of content together and then creating channels by slicing and dicing that content by theme, type, subject matter, talent, show title and territory, MCNs (and all the channels under their umbrella) benefit from the huge footprint these networks have established.

Content formats and durations

The optimal duration for videos on YouTube is arguably one of the reasons production companies up until now have not used the platform in the same way as other social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. And the more YouTube pivots towards being a FAST streamer (or at least, a platform for both short form and long form video), the more optimal durations can be a tricky barrier for producers to overcome due to rights issues.

To explain, YouTube has two main formats (ignoring live at the moment):

Standard - 16:9, minimum optimal length 10 - 14 minutes (over eight minutes to be able to carry a mid-roll advert, not just a pre-roll)

Shorts - up to 60 seconds in length, vertical orientation of 9:16 (similar to Instagram reels and TikTok).

The duration issue creates a catch 22 for some producers, as programming that is made for TV fits perfectly into YouTube’s standard format, however the rights for longer durations might not sit with the production company. Meanwhile, the company might have the rights to publish content that matches the shorts duration, however the vertical format requires resourcing to deliver it.

This issue with duration ties back to rights, so being clear on what can be published and then exploring if more permissions can be sought is important. Separately, vertical format content creation could be added as a requirement to all current and future productions.

Monetisation

There are several ways to monetise on You Tube:

Google Ad Sense - pre, mid, post roll advertising plus some display formats

Sponsorships - where a particular brand pays to buy out a channel or content type

Sales promotions - so memberships, promote merchandising etc.

The benefit of Google Ads is once an account is verified and generating a level of views, it can be switched on at a click of a button. Advertising is sold on a CPM basis, which is cost per mille or cost per 1,000 views. YouTube usually keeps 45% of the gross income, so producers get 55% which at the moment is around £3 per thousand views (although it can be higher all depending on the content). So in very simple terms, that equates to £300 for 100k views or £3,000 for 1 million views.

Usually this is the heart sinking moment for TV producers - goodness, the effort required to get to 1m views is a lot, and all for only £3k in revenue. And yes, it is a commitment to get a channel going and grow it. However, for any channel with chunky views and audience engagement, YouTube ad revenue will not be its only income stream. They will be making money on all the other social platforms, as well as sponsorship and direct sales.

Plus the repackaging of archive shows can open up new markets for these titles - in the TellyCast interview below, James Loveridge from Little Dot Studios talks about how some old shows have found new audiences via YouTube, which in turn has resulted in additional broadcast sales.

Compilations and content formats

When looking at how TV shows are used on YouTube, the common formats are as follows:

Full shows - fairly obvious! Most archive shows are non-exclusive, although may have clearance issues that need to be considered.

Clips/extracts - these will be short direct extracts from the completed show. Depending on the broadcaster, production companies often get promo clip rights as part of their commission.

Trailers - marketing trailers usually made by the broadcaster/streamer

Behind the scenes - again, depending on the broadcaster and commissioner, production companies may have to supply or create BTS videos that can be used on social for marketing purposes

Compilations -one of the key bread and butter YouTube formats which usually aren’t routinely created as part of the broadcast process.

The compilation opportunities for TV producers are endless: full episode compilations, shorter classic moments, bloopers, how tos, cut down episodes, practical information, memes, reveals and so on. Related to the earlier point around durations, longer compilations or episodes stacked up together are in demand on the platform, so consider the 10 - 14 optimal length a floor rather than a ceiling. Great examples are kids channels such as Bluey managed by BBC Studios (as parents appreciate not having to click play or next at the end of every video).

Or Banjiay Comedy’s channel - where they’ve cut together 60+ minute videos of best moments from particular shows and talent - so classic Sean Lock moments or mega mixes of the best of 8 Out of 10 Cats.

And the more users watch YouTube on connected TVs, the more appealing these longer durations and compilations will be (more than half YouTube viewing happens on the TV set already).

TV production by its nature is a forward looking venture - where’s the next commission coming from, what’s the next big idea - but to succeed on YouTube it is important to look at old shows in new ways. What relevance does this old content have today? Can it be sliced and diced in a way that is completely different to the broadcast version, but may be of interest to new audiences?

So thinking tangentially across episodes, series, genres, talent and themes is a key approach, as is using audience research for inspiration of what might resonate. For example, the most popular video on Channel 4’s 4Homes channel isn’t a classic reveal moment, but instead is this 16 minute video of 3D animations from Grand Designs episodes stitched together.

Here are some examples of production company channels (I’ve created a YouTube playlist of videos from production companies and will keep adding to it over time):

Wall of Entertainment (mentioned last week) - 155m views

Banjiay Comedy - 121m views

Zandland - 3.1m views

Little Dot’s network of factual niche channels:

Real Stories - 1.1bn views

Timeline 1.1bn views

War Stories - 227m views

Odyssey - 172m views

Chronicle - 125m views.

North One’s main channel has 51m views, then a bunch of other channels:

Travel Man - 45m views

Fifth Gear - 364m views

The Gadget Show (which is now a podcast & website) - 50m views.

Total views is a very blunt way of viewing success on the platform. After all, some of these channels might have built these views over five years ago. Others might be hitting their stride now. Some might not be seeking views but targeting a smaller demo and are using for YouTube as marketing for an off-YouTube activity. And so on. However, they are useful in demonstrating the appetite for particular types of content, and how successful the channel owner has been in getting the algorithm to promote the content and then in turn, getting users to click to watch.

Last point. If you want to get serious about using YouTube as a FAST channel (Free Ad Supported TV) for full episodes, then as a rough guide, around 200+ hours is needed, plus a regular amount of content to refresh the offering. This is an entire business strategy in and of itself which is too much for this post, so will pause on this subject here.

Tags, metadata, titles, thumbnails

It is no secret how important the title of a TV show is for linear TV and listings.

In the world of YouTube, what is important is the video title and thumbnail image, then the tags, description and other metadata to help get the video to come up in search, and then be enticing enough for a user to click on it (of course, the video must deliver on the promise of the title and thumbnail).

In terms of titles and labels, what works for TV often doesn’t work for YouTube and vice versa (especially for factual). Think of how many titles of successful factual shows are puns or plays on words. And then go to YouTube and rarely will you see successful videos titled in this playful manner. What works in that environment is something much more Ronseal and descriptive, often as a list or countdown (‘Top 10 house build disasters”) or something with a hook ("‘I ate a toad and you won’t believe what happened next”).

In summary, unless the title of a show is very well known, naming videos by thinking about what users might be searching for and how the video will help or interest them is important.

Playlists

YouTube’s functionality to aggregate content together from across the platform within a channel is hugely useful to production companies as it helps create a way round the rights issues already mentioned.

As an example, Zandland’s channel has playlists to aggregate their shows from broadcaster/publishers’ channels, thus enabling the user to see all their content together, but each video remains wherever it is published. So the El Salvador film below is published by Zandland, while The Inside Truth is on the Channel 4 channel.

This is a helpful tool especially for those production companies that don’t have many rights to play with.

Audiences

The post last week on the importance for TV production companies of building direct relationships with audiences is all relevant here.

YouTube is home to all sorts of cultures and communities, and is a key place to find your audience, understand who they are and what they like, as well as discover new audiences and TV show ideas. This is a great place to find your tribe, give them what they love, and they will then in turn become advocates for you.

On a practical level, it is important to keep an eye on user comments on videos, as these can be spam.

Publishing schedule and analytics

As mentioned at the start, while there is a piece of work to get your channel going, the task is never done. The mode is one of being constantly curious, testing out new ideas, studying the data and analytics, seeing what works (and what doesn’t), talking to your audience and then trying out new things.

In the Tellycast video above, Little Dot Studios’ James Loveridge says that in his view YouTube doesn’t want to be a destination only of old legacy stuff sitting there forever - rather, it is new creators, channels and content that are prioritised.

So what now?

How a production company builds out its YouTube channel depends on how much content they have to play with, how appealing it is to audiences, and how much capacity and resource is available at this stage.

At a high level, here is a process that can help to get started on the platform:

What is the objective - for example, to understand the platform and build a new creative specialism, market individual shows, make money, build the company brand, road test new talent, drive sales such as programme sales to new territories, merch and so on

Who is the target audience (or audiences) - identify these people and then have a look and see what else is out there for them and their interests

Content and rights audit - the full list of hours, what the associated rights are (can any more be negotiated?), and any clearances that are insurmountable

YouTube trawl - look for all of the company’s content already published to the platform, and group it by type (clips, full shows, trailers, behind the scenes and compilations) and by who - for example, broadcasters, distributors, partners, participants or users

Draw up a playlist plan for how to divide up the content on the new channel - say by shows, or by full episodes and trailers/clips, compilations, themes

Create a channel and then create these playlists - adding all the content already published to YouTube to these playlists.

This will result in a rudimentary YouTube channel for a production company. The next practical step is to consider a company’s portfolio overall and create a regular schedule. This includes the website, YouTube channel, Facebook page, X profile, Instagram and TikTok, plus a newsletter. The goal is to keep them all updated and not let any of the channels become neglected. So for example, vertical video content made for YouTube shorts can work on Instagram and Facebook reels and TikTok. Although these platforms have distinctive audiences, so developing content tailored to each platform is useful at a later stage.

The next phase is to draw up a longer term plan that matches up to the company’s objectives, and ensure that this is baked into the organisation at all levels. Depending on what a company is seeking to achieve, this can involve encourage producers to consider YouTube as an original creative outlet in its own right. Why and how to do this, well, that will be the subject of a later post.

Finally, little bit of YouTube nostalgic inspiration. This week, a video has done the rounds with the backstory of OK Go’s music video hit from 2005, which was one of the first big viral videos on a tiny new website called YouTube - so tiny and new, that the founder Chad emailed the band to ask them to host their video on the website.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Odds and ends

C21: Animaj unveils ‘new era’ AI tool to disrupt traditional kids’ animation industry (thanks to

and Futher&Better)Digiday: Why the ad industry is redefining what it means to be a creator vs. influencer (thanks to

and TV Futurist)Sequoia Capital’s latest take on the future of generative AI.

Follow @businessoftv on Twitter/X, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

I’m a huge fan of Stephen Colbert’s Late Show and watch his nightly monologues here in the UK on YouTube. CBS must be generating a large international audience and at least some ad revenues by doing this. It’s another example of a broadcaster using YouTube to increase reach.