The state of US reality TV; Meta's wearable glasses; & what Nicole Kidman's wigs can tell us about streaming.

Plus a little bit on Amazon Studios, how one production company built its fanbase and makes money from merch, and a statistician tests Kevin Bacon.

This week, I’ve written about a subject that often divides people into those that get super excited and those that hit the snooze button - wearable tech and augmented reality. No wait, come back!

I’ve also covered a snippet from an interview with the heads of Amazon Studios/Prime Video, plus a rather dispiriting piece on the state of reality TV in the US, but possibly (hopefully) reflects opportunities for UK based production companies.

As for companies with innovative business models to be inspired by, this week it is Sydney-based indie animators Glitch Productions and their approach to IP, community and merchandise (thanks to Jodie Morris for the tip off).

I’ve also included Nicole Kidman’s wigs to illustrate how audiences can get frustrated with so-called advances in the streaming age. Plus a fun post on Kevin Bacon and statistics.

Before diving in, a quick newsflash: I wrote again about the various tech company court cases last week, and on Wednesday the US department of justice confirmed they are considering a range of measures against Google, including the breaking up of the corporation. The reason this situation matters to TV and film producers is the outcome, depending on which way it goes, could have an impact on all of us - perhaps by disrupting the online advertising market, or even the ownership and direction of YouTube itself. Plus, the US government is also suing Amazon and Meta, so there may be wider knock-ons to US tech companies and therefore to the online and TV markets.

The future of wearable tech

A few weeks ago, Meta launched a new range of wearable tech. Called Orion, they are dubbed Meta’s ‘first true augmented reality glasses’ with users being able to view virtual screens for work, entertainment or personal organisation.

In lay terms, augmented reality (AR) is where, well, reality is augmented. As opposed to virtual reality (VR) where you are viewing a completely virtual world usually via a headset, AR involves a layer of augmentation when you observe the real world via a screen such as a smart phone’s camera app, or in this case, a pair of glasses.

VR and AR have long been of interest to TV and film because 1) of their ability to act as a new distribution point for programming 2) they can enhance the storytelling experience and 3) they offer new immersive opportunities for advertisers and commerce. As examples, 59 Productions created the Grenfell Tower VR project to compliment a Channel 4 documentary and Apple created the ‘For All Mankind: Time Capsule’ AR experience to extend the TV series. Both Amazon and Netflix have been looking into AR and VR projects.

These sorts of tech announcements do have a usual pattern to them. Firstly tech lovers get massively excited - these are a game changer, the real deal, a huge technological advance, this is the one that is going to go mainstream.

Others then question how plausible or even desirable the user cases are for a particular type of tech - in other words, how likely is it that ordinary people will want to walk about wearing glasses and use them to do Zoom calls or look up the weather?

For some, they see the potential for wearable tech such as glasses to be a helpful personal assistant, similar to an iWatch. However, glasses by their nature are much more invasive than a watch. As an example, I once had dinner with someone wearing Google Glass, and it was a deeply unsettling experience. Their eyes regularly were flick up top left and top right to look at the glasses to read messages or search for something on the internet. Imagine someone constantly looking at their phone, but with only an eye flicker rather than a hand gesture the signal that you’ve not got their attention - as shown by this promotional image from the time (Google Glass was discontinued in 2015):

The big elephant in the room remains privacy. This video by students at Harvard is interesting, where one of the students walks around with Meta’s current Ray-Ban glasses on and uses them to look up people’s personal data.

It is worth pointing out that Meta said to the Times that the glasses themselves don’t have facial recognition technology, rather the students are using publicly available facial recognition software on a computer that would work with photos taken on any camera or phone.

Finally, while we often talk about tech companies as a group, it is worth remembering that each one is different, and each one is facing its own challenges. As Greg Isenberg observed when Mark Zukerberg said at the launch of Orion that glasses would replace mobile phones by 2030: “Meta is suffocated by Apple and Google App Stores. They need glasses to win.”

Either which way, these new technologies aren’t having a significant impact on TV or film - yet. But it is likely they will do in the years to come.

The state of reality TV in the US

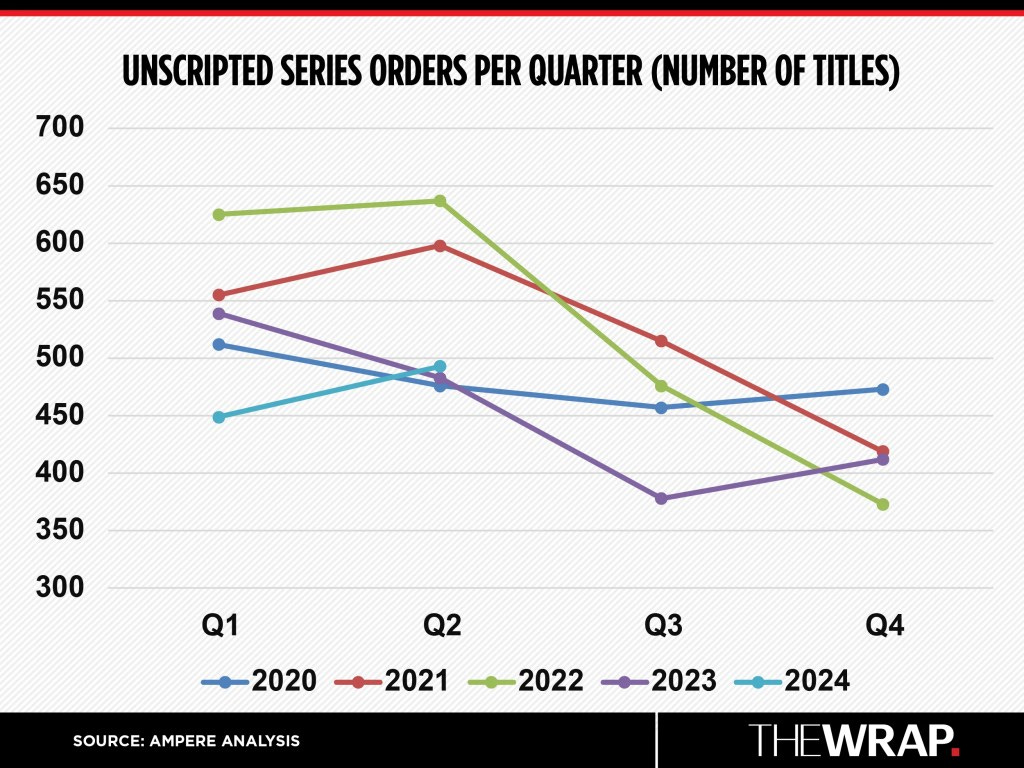

The Wrap has an interesting piece on the decline of reality TV commissioning in the US. It includes this graph:

I’d love to see a similar graph for the years before 2020, as the 2020 - 2023 years are so skewed by Covid. As the piece explains:

…studios have broadly consolidated amid a spate of mergers — which has left fewer buyers in the marketplace — and tightened budgets across the board.

Beyond official orders, one reality TV insider estimated that between 30-50% of the unscripted projects currently in development are believed to be in limbo due to uncertainty inside some of the sector’s most committed buyers — particularly WBD and Paramount Global. There was also a glut of unscripted programming in production when the COVID pandemic shut down scripted shows, which has now course-corrected.

Beyond these issues, reality TV is facing the same fundamental challenge as the rest of the TV industry: the traditional revenue model often (but not always) depends on selling into one geographical territory and distribution into other countries. With the streamer global cost plus model, where there is no opportunity for international sales, combined with a reduction in volume as streaming platforms don’t have the same hunger for volume as schedule-driven TV, it is increasingly hard especially for smaller producers to be profitable.

The article is gloomy about the state of reality TV in the US and Hollywood, which could be seen as representing the opportunity for UK-based production companies to compete and win commissions, albeit with increasingly squeezed budgets (quoted below is Mark Koops, creator of ‘The Biggest Loser’ and other reality formats):

in his Substack Always Be Watching made the following observation about the article by The Wrap:These days unscripted shows … are more likely to hire local crews and fly their U.S. contestants abroad than shell out a higher cost to keep their U.S. staffers.

“Salaries and compensation in the U.S. are just higher and they’re used to bigger teams,” Koops said. “Some of this now, with so many people not being employed, is because you just can’t afford to have as many people on any one show.”

The entire story isn’t just that cable TV is going away and that reality TV shows are subsequently being impacted - it’s that reality as a format is now also being challenged by YouTube and TikTok with that casual-to-watch reality experience now met on-demand and algorithmically supercharged by these platforms.

Separately, another pressure on the reality TV genre comes in the shape of broadcasters and networks finding other formats that perform as well if not better at a cheaper price point. So for example, if you look at the History Channel schedule, there are archive shows which are cheaper to produce than reality shows, topped, tailed and voiced by a celebrity like Morgan Freeman.

Cost Plus versus Territories

As mentioned above, the cost plus model has been seen as ‘the’ model for the streaming age. However it has become just one option for platforms over the last few years, and instead flexible territory-by-territory deals are increasingly common.

This morning there was a Variety interview with Jennifer Salke head of Amazon MGM Studios and Kelly Day, VP of international for Prime Video which touched on this very subject. When asked whether Amazon is moving away from the cost plus model towards a more traditional model, Kelly Day said:

It depends. We actually prefer to keep the rights globally where we can but we have been much more flexible, in particular in Europe. We’ve got a number of deals where we either share rights with a broadcaster … or in some cases leave them with a producer and just take select territories then let them distribute other places around the world.

There was another line in the piece that might be of relevance to the UK production community, where they were asked about which arm of the company UK drama producers should be pitching to, following the acquisition of MGM. Jennifer Salke said in response:

I think you’ll see over the course of the next couple of years just a bigger investment in the footprint we’re building here [in the UK], as far as the infrastructure, the teams, and there’ll be clarity around that.

How merch (and community) can be a revenue stream for producers

The upending of the traditional TV business model is a huge part of the current volatility in our industry. And if those traditional models don’t (or can’t) reassert themselves, then perhaps the companies that will win in this new world are those which can merge together innovative funding, distribution and additional revenue streams with top quality content to reach a specific audience through all the noise. Easier said than done, right?

Following on from the interview with Mark Duplass where he gave his thoughts on this theme, this week a post by Jodie Morris (kids digital engagement & distribution expert, ex of Acamar Films, Beano Studios and Channel 4) highlighted another company taking a very interesting approach.

'The Amazing Digital Circus' is an adult animation series by Glitch Productions which built its audience on YouTube before being acquired by Netflix.

The upside for Glitch is they’ve retained creative control, and as the deal is non-exclusive, they can keep their YouTube audience while also receiving licensing revenue from Netflix. As for Netflix, well, while they are sacrificing exclusivity and creative control, they are able to acquire a title that is an evidential hit which comes with its own ready-made fanbase.

As Jodie ponders:

It'll be interesting to see how this all plays out. How will the series perform for Netflix? Will Netflix availability have any impact on ‘The Amazing Digital Circus' YouTube performance? Will this finally prove the theory that exclusivity limits your audience, and that ultimately all boats rise? And, if it all goes well, will Netflix want to commission a future series and have more say, or will Glitch hold on to their autonomy for the long term?

In addition, this may be an appealing way to pushing the development costs and risk onto production companies by platforms/broadcasters and studios, who traditionally use their deeper pockets to finance the process of finding hits.

What is (even more) interesting about Glitch is that their revenue model isn’t simply about making an IP famous on YouTube and then licensing it for a fee to platforms like Netflix.

Through their 11m subscribers on YouTube and a membership community called Glitch Inn, they have a direct relationship with their fans. Worth noting the founders started out as content creators on YouTube, so creating and publishing content directly to audiences and building a community must be second nature to them.

In addition, it appears another important leg of their model is merchandising. They have their own online shop full of merch for their shows, and also have their own merchandising company, the tremendously named FinalFinal Project.

So their business model appears to be: Make their IP famous on YouTube, provide a community for fans, create merch their fans will love, take licence fees from a streamer, get the streamer to increase the size of their fanbase, get these fans to join in the community, sell even more merch to this much bigger audience.

This has resonances with the other key takeaway from that Mark Duplass interview - that is, the growing importance for production companies to view their shows more as products, rather than leaving the direct-to-consumer activity up to broadcasters or platforms. When shows are viewed as products in and of themselves, this can open up audience building, marketing and merchandising opportunities similar to how Glitch has approached its portfolio.

How technological advances aren’t always warmly received by audiences

Technology is changing all aspects of TV and film: not just how content is distributed, the audience’s viewing experience and how content is monetised, but also the format and product of the TV show and film itself. In the last month or so, I spotted several very different examples that together illustrate how wide ranging these changes can be, and that they are not always perceived as being for the better by audiences.

Firstly, there was a pretty unvarnished discussion online about Nicole Kidman’s wig in ‘The Perfect Couple’, and how 4K doesn’t necessarily improve the viewing experience as it shows up things like wig netting or make-up, acting as a barrier to the viewer becoming immersed in the story. The discussion moved on to be more broadly critical in the way some online conversations can be; the gist of the argument being despite the big budgets, streamer production values wouldn’t have been acceptable in Hollywood of days gone by. I mention this conversation because irrespective about the validity of these arguments, what is interesting is the number of people who shared similar frustrations, thus suggesting this is a real audience sentiment.

And yes, I did about 10 screenshots before I could capture Nicole saying this very apt line:

Secondly, several people observed the relative lack of popular cultural impact of the top film titles in the recent Netflix data dump of ‘What We Watched’ - commenting that if 100 million people watched a film it should be more embedded or visible culturally than these titles are. An example of this sentiment is below:

Thirdly, there was an interesting discussion online where many people were bemoaning the now and next functionality on streaming platforms disrupting - literally and psychologically - the experience of watching a TV show or film.

To illustrate this point there was this example where the final iconic ending of ‘Psycho’ was interrupted and made screen-in-screen for a promo to watch ‘Big Bang Theory’ on iTunes/AppleTV.

And finally, when Kamala Harris announced that she was going on the ‘Call Her Daddy’ podcast, Asian Business and finance editor for The Economist Mike Bird observed how culturally siloed we’ve become as he’d never heard of this particular podcast despite it obviously having a significant enough audience to land this interview.

As he said in a subsequent post “I know that's my ignorance, but it does just make it a lot easier to be ignorant when everything is so splintered.” And another user made this astute point: “There's still a monoculture (everyone knows who taylor swift is). It's just that subcultures can get WAAAAY bigger now without ever breaking through to the mainstream.”

These posts together in their own way are all voicing different frustrations with elements of our new TV and film viewing (and audio listening) experiences. Irritation with advanced 4K resolution meaning that the viewer can’t be immersed in a story as they want to be; a dislike that TV and film is treated simply as ‘content’ rather than storytelling art forms; frustration with the now and next promotions of online streaming platforms that interrupt a filmmaker’s storytelling; the fragmentation of our popular culture meaning we lose shared moments and are increasingly siloed.

It is highly likely that those running these businesses will be acutely aware of some if not all of these frustrations, and probably spend a huge amount of time thinking about these challenges. And as art forms, TV and film are great for sit-back storytelling. They’re also really great at the popular culture thing and creating shared cultural moments. So as pendulums swing, maybe a trend to watch for will be a return of more shared moments outside sports and news in 2025 and 2026?

Statistically speaking and Kevin Bacon

I thought I’d end with this enjoyable piece by

exploring the statistics behind the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon game. Using various statistical methodologies, it shows that while Kevin Bacon is not the most connected actor in Hollywood, he is a great actor to use for the game because the most connected actor (no spoilers, but you can probably guess who) is just too obvious and would make the game too easy.