The hit to flop ratio and how we view risk in the age of data

Plus Netflix's challenges despite its Q3 smash results, and the state of the games industry.

Our industry is all about dreaming of hits - knock out ratings, box office success, returnable formats that go on for 10+ series, five star reviews and golden awards. But so often, shows or films are middling, or sometimes, flat out flops. This week,

wrote a great piece where he explores how we view flops, especially in the age of streaming and mass data.I’ve also covered a little about Netflix and what challenges lie ahead after a sterling Q3 performance.

Finally, a little on the gaming industry which is having its own difficulties.

Flops, hits, and how we view risk in the age of data

Much has been written about Joker: Folie à Deux: how and why it was made, what the film’s performance means for Warner Bros. Discovery, the size of the budget ($200m) and how much money it is likely to lose (again, possibly $200m).

Considering how tricky things have been over the past couple of years, it wouldn’t be unusual to have a sky is falling on our heads response to this one flop. However

has instead made a compelling argument that risk and failure is crucial to the creative success of the TV and film industries. His article is called ‘Flops for Dummies’, and there’s also a podcast episode on the same subject (it covers other topics of interest to UK producers including the state of the UK branded content market, so worth a listen - it is 42 minutes long):The thrust of Richard’s argument is that for eons, shouldering some flops while aiming to have a couple of hits was the accepted balancing act of TV and film. However, in the streaming age where tech companies have upended many of the established ways of doing things (what he calls the age of ‘big IP’ and ‘big data’), has resulted in the rise of a fallacy that risk is both optional and avoidable.

Using data within broadcasters and networks isn’t new. Spend any time with research & insights, scheduling or ad sales teams to understand how knowledgable and analytical traditional TV decision-making has been for decades.

However, streaming over the internet has created a whole new mass of data from many different sources: user data when streaming via a broadcaster’s own services on connected TVs, websites or apps; data from ad tech platforms; customer registration data; third party data from places where programming is distributed from Sky to Freeview and so on. Depending on what data is shared, this can tell us geographical and demographic information, where and what users watch, what they search for, what they click on (and what they don’t click on), when they stop watching and much much more.

All of this is exceptionally useful to the streamers’ teams of engineers, technologists, product specialists and designers who are focussed on solving users’ problems and make things better, more efficient, more effective. These teams’ skills are vital and essential in building and running TV-like services: platforms, distribution, the entire tech stack, user experience layers, audience research, ad tech and more. These all rely on first rate engineering capabilities.

This could be considered the blending of art and science - boffins and artists - that Eric Schmidt, chairman of Google, called for in his MacTaggart lecture at the Edinburgh TV Festival in 2011.

What is tricky is when data is used in the creation of TV shows themselves, especially if it is an attempt to predict what titles will be hits and what won’t.

What constitutes success or failure in TV (and film) can be defined as a post event diagnosis. So we only know what is a hit after it has been released into the wild to be adored or panned by audiences, and it is impossible to predict beforehand what will work, and what won’t. Even when all evidence suggests a hit in the making, this can still be wrong. After all, the first Joker movie grossed over $1bn, so surely a follow up would be a guaranteed winner?

Everyone involved in making shows and films will have those head-scratching titles, so sure it is going to smash it out of the park, and yet it barely makes a ripple. We then look for the why - was there something better on the other channels? The weather? A world event to distract people? The marketing? The scheduling? And then look at the show itself - was it the characters? The story? The talent? The subject matter or premise? The title sequence? And even then, after much pondering, it is still possible to be none the wiser why one title worked and another didn’t.

To put it another way, via a West Wing reference, success or failure for TV and films can lean into a 'Post hoc ergo propter hoc’ fallacy as Jed Bartlet explains:

That is, not only does something become a hit or a miss after the event and can’t be predicted before hand, we often then ascribe the show’s success or failure to things that may not have been the cause at all.

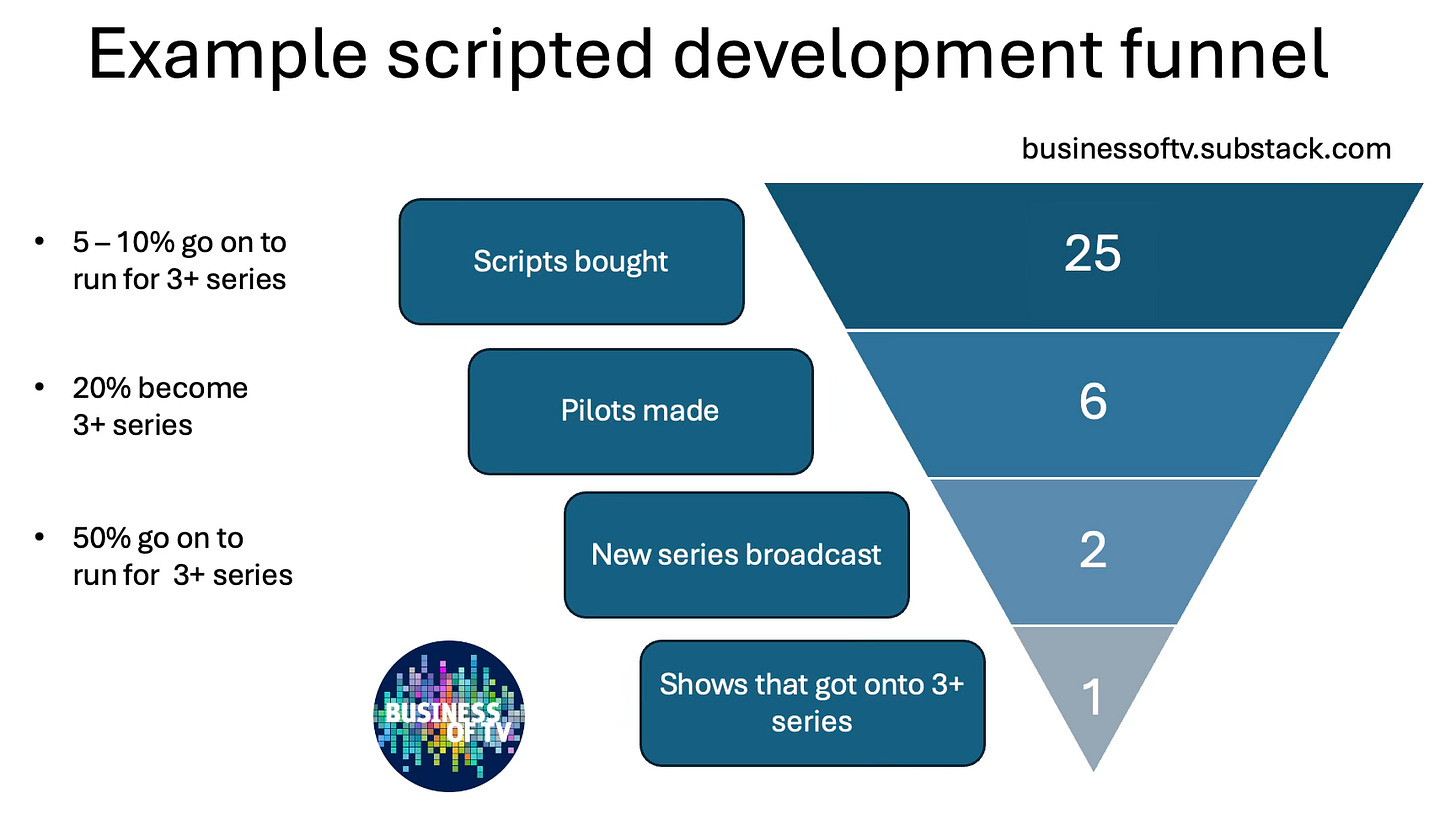

To find hits, TV has long used a tried and tested funnel approach. Below is an example development funnel for scripted TV.

These funnels aren’t rigid, rather depending on the platform or the network, some might buy more scripts, or put a different percentage into pilot, or have a better or worse strike rate than this example. A channel that is on fire with a lighting-in-a-bottle leader might have a better strike rate. Or a channel that is struggling might have a worse rate, all dependent on a variety of factors.

But in general, the model for scripted development follows a similar path to the above. Inherent in this model is an acceptance that to get a hit, the majority of shows will be cancelled, or indeed won’t even get beyond the script stage. In the age of big data, you can see the appeal of a problem-solving analytical approach that aims to fundamentally alter the hit to flop ratio - perhaps to the point that flops largely cease to exist.

For some, this is a desirable outcome. However going back to Richard Rushfield’s argument, he says it is wrong-headed to even try to reduce the number of flops - because flops are an inherent part of finding hits. He writes:

Show me a mythical year where there were zero flops, and I will show you a business that was making very safe and predictable projects, which might have worked out fine for it this year but is an inch away from boring everybody right out of the theater.

By prioritising risk reduction, there is a danger of putting audiences into a “coma of apathy and boredom”. He quotes

, who “… described entertainment as the failure business…” because no one can predict a hit, and no algorithm can do it either. That is the alchemy of TV and film.Richard’s piece (as often is the case) is a punch in the arm for creators and financiers to not just continue to take creative and artistic risks, but actively embrace risk and the necessarily failures that come as part of creating hits. He includes the crucial reminder that it is important to “keep the pipeline pumping to find your way to those hits”.

I could quote the piece at length (but I won’t - do read it for yourself) as it should have resonance in how we understand risk and failure in the TV and film worlds. He ends with the following:

About eight years ago, as the streaming race was heating up, a very wise producer shared a prescient prediction with me. The streaming race will be won, he said, by whichever company has the greatest appetite for failure. Because that company will find its way to the greatest number of hits.

So companies that will succeed are those with the confidence to take risks and stomach failure - along with the ability to use data to its full potential while respecting the creative process of TV and film creation.

Richard finishes by saying in his opinion the company with this approach at the moment is Netflix, which leads on to….

Netflix smashes revenues and subs, and yet…

Netflix’s Q3 results knocked it out of the park both in terms of revenues and subscribers (up to 282m). While the company is dominating the subscriber streaming film and TV-like market, there have been quite a few ‘…and, yet’ observations over the past week from commentators.

The biggest most obvious challenge Netflix faces is YouTube. Matt Belloni of Puck News (£) has done a deep dive into the current landscape for the company, and notes that while Nielsen Gauge suggests Netflix and YouTube are within spitting distance of each other in terms of time spent on platforms in the US via smart TVs, when looking at ad-supported streaming consumption worldwide, data from Owl & Co shows YouTube has 350% more viewing hours than Netflix. This puts the Google-owned video platform so far ahead it is hard to imagine any company catching up without significant investment and a whole new product offering.

The next issue Netflix faces is advertising. The share of the ad market that YouTube has is significant, and on top of that Amazon has jumped into advertising with both feet - making their ad tier opt out rather than Netflix’s approach of opt in, thus flooding the ad market with something like 200m users. This combined with the depth of Amazon’s customer data and breadth of their advertising offering across all of their platforms and services beyond video… well, together this makes them hard to beat, plus obviously will have a significant impact on the UK’s advertising market for broadcasters like Channel 4 and ITV.

Matt Belloni makes another observation about Netflix both in terms of its overall revenue but also its lack of diversification in comparison to other players. The company generates less revenue than its peers as they all have other revenue streams outside of streaming video subs and advertising. Disney has theme parks, merch and so on and generated more than double Netflix’s revenue last quarter. Amazon, Google and Apple dominate eCommerce, search, devices and more, and as Matt says “..are way bigger and could buy Netflix tomorrow if they wanted to (DOJ [department of justice] willing).”

These challenges would be enough, however the issue of cinematic versus streaming releases keeps reappearing, most recently in a reported ding dong between Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos and Daniel Craig. While cinematic versus streaming release isn’t a challenge to Netflix anywhere close to the one posed by YouTube, the issue does usefully demonstrate how distinctive the streaming subscription model is to the established approach of broadcasters and studios.

As

has repeated documented, cinematic release of films is the clear winner over streaming in terms of generating revenues as well as creating impact with audiences. In a piece from 2023 called ‘The Data Is In: Theatrical Films Massively Outperform Straight-To-Streaming Films’, he said with the following graph to illustrate the point:Historically, films went through a series of “windows” .. starting with theaters, then going to home entertainment, then to pay cable, then to regular broadcast TV and cable. Nowadays, streaming is concurrent with pay cable…. It seems obvious—to me at least—that you can’t collapse all those windows and expect to make the same amount of money!

For Netflix, releasing first in cinemas simply isn’t their business model, and it is proving tricky to align the desire of filmmakers and talent to have the cultural impact of cinema with Netflix’s direct to consumer model.

As

says in a post on Too Much TV, Netflix is a subscription based business model which is diametrically opposed to how a traditional studio does business, and “every decision they make is in service of that goal.”He compares the studio approach: “Traditionally, studios focused their efforts on making sure each individual movie or TV series was a success” while for a subscription-based business, “each decision it makes is based on increasing revenue from subscribers, lowering new customer acquisition costs and preventing subscriber churn.”

Understanding their goals helps explain why, as Matt Belloni observes, that Netflix “…continues to conflate eyeballs with experience and impact”. That is, yes, Netflix has the biggest subscriber base in the world, but this doesn’t result in the biggest cultural impact with global audiences that continues to be possible with cinema. Which - at the moment anyway - is totally fine with Netflix as it is in line with their business goals.

A few details on the state of gaming

Games have often been thought of as one of the reasons the TV & film sectors are in the state they're in (as people are believed to be playing games instead of watching TV & going to the cinema). However, things have been really challenging in the gaming industry too. Thus far this year according to Eurogamer, 13,000 employees are believed to have lost their jobs, in addition to the 10,500 workers laid off in 2023.

Peter Kafka a few weeks ago covered the issues facing the gaming industry in his Channels podcast, which has many resonances with the TV and film industries. Listen below, the section on games starts at around 32 minutes in:

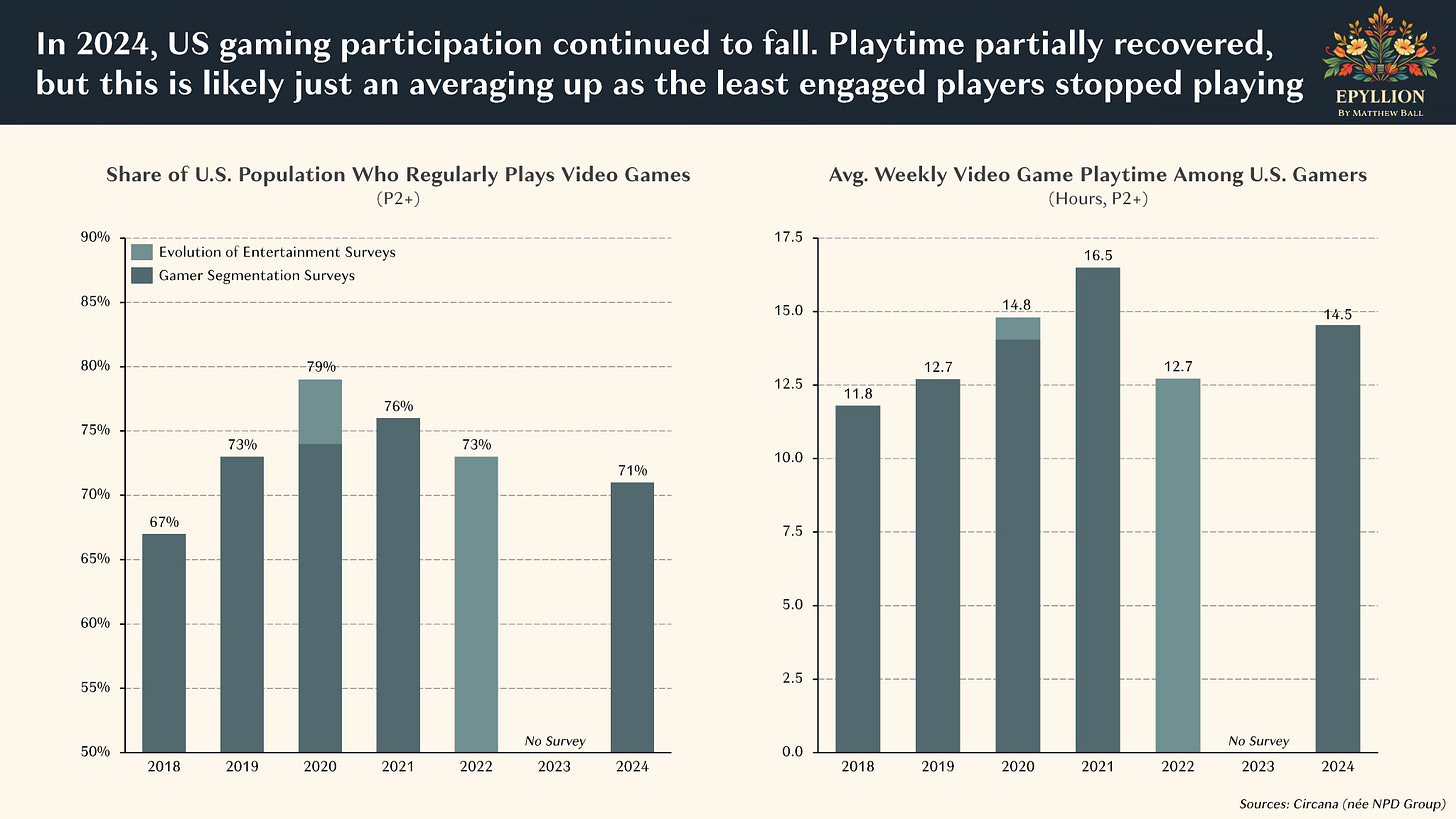

Matthew Ball who writes regularly and insightfully about the games industry also made the following post showing that US gaming participation has dropped to pre-Covid levels.

And finally, you might remember that Netflix hired Alain Tascan from Epic Games (creators of Fortnite) to run their games division, and this week it was announced they are shutting their AAA studio (triple A, meaning super expensive tentpole games like Halo or Call of Duty). Triple A games have a lot in common with big film franchises - big swings, budgets that can be $200m plus marketing, potential great rewards, but if they aren’t hits they make big losses.

This hints that Netflix is more interested in creating smaller more casual games around their existing IP, however it will take some months if not longer for a clearer picture to emerge.

Other odds and ends

Is there a difference between an agent and a manager? An interesting post by

outlining how the concept of agent, manager and publicist differ in the UK from the US.The rise of AI ‘slop’: There’s something off about this year’s “fall vibes”

Follow @businessoftv on Twitter/X, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.