Return of the rom com, factual TV's squeezed middle, and will a model emerge to finance longer TV seasons?

This week, I’ve covered three recent trends:

Are audiences seeking the longer seasons of the traditional linear TV era, and if they are, will a streaming business model emerge to make them profitable?

The squeezed middle of factual TV - what does it mean for TV producers and how will new formats of the future be funded?

Female skewing rom coms and melodramas are back - but is it risky to let specific genres fall out of favour?

Together, these themes prompt several related questions: have much loved genres and formats been left by the wayside in the wake of the streaming revolution? Do new business models exist to create all the different types of content people enjoy, and for companies, especially new ones, to grow and become profitable? And if these business models can’t be found, is there an increasing risk of people breaking their viewing habits entirely?

Before diving in, a quick thank you for subscribing, and I hope this email proves helpful to you. If you find it useful, please do share it with your colleagues or anyone else you think might be interested.

Shrinking episodes and seasons

A clip of a recent Marlon Wayans interview was posted on X by

last week, where Marlon nailed how the current streaming model isn’t working for talent and producers such as himself, in comparison with the syndication model where he had to do 100+ sitcom episodes which were then sold market by market. He says: “You got to think about the business of the business, and right now our business is gobbling itself up"…(Irritatingly, X continues to not allow embedded tweets on Substack so I’ve uploaded the clip or you can you can watch the full 2+ hour interview on YouTube at Club Shay Shay.)

While Marlon’s analysis is interesting in and of itself, the responses to Myles’ post were also enlightening as a whole bunch of TV fans voiced their desire for the return of longer running scripted seasons which formed the backbone of linear TV schedules. To single out a few comments:

“I’m tired of eight episodes seasons, especially when you only get them every two years.”

“I just want to be able to channel surf again. I’m tired of being so intentional about what I watch.”

“I’m tired of like really great shows that last for 2 8-episode seasons Give me 9+ seasons with 20 episodes each, because I’m over here binging shows from the early 2000s that lasted like 10 years and only had 12mins ate up by commercials.”

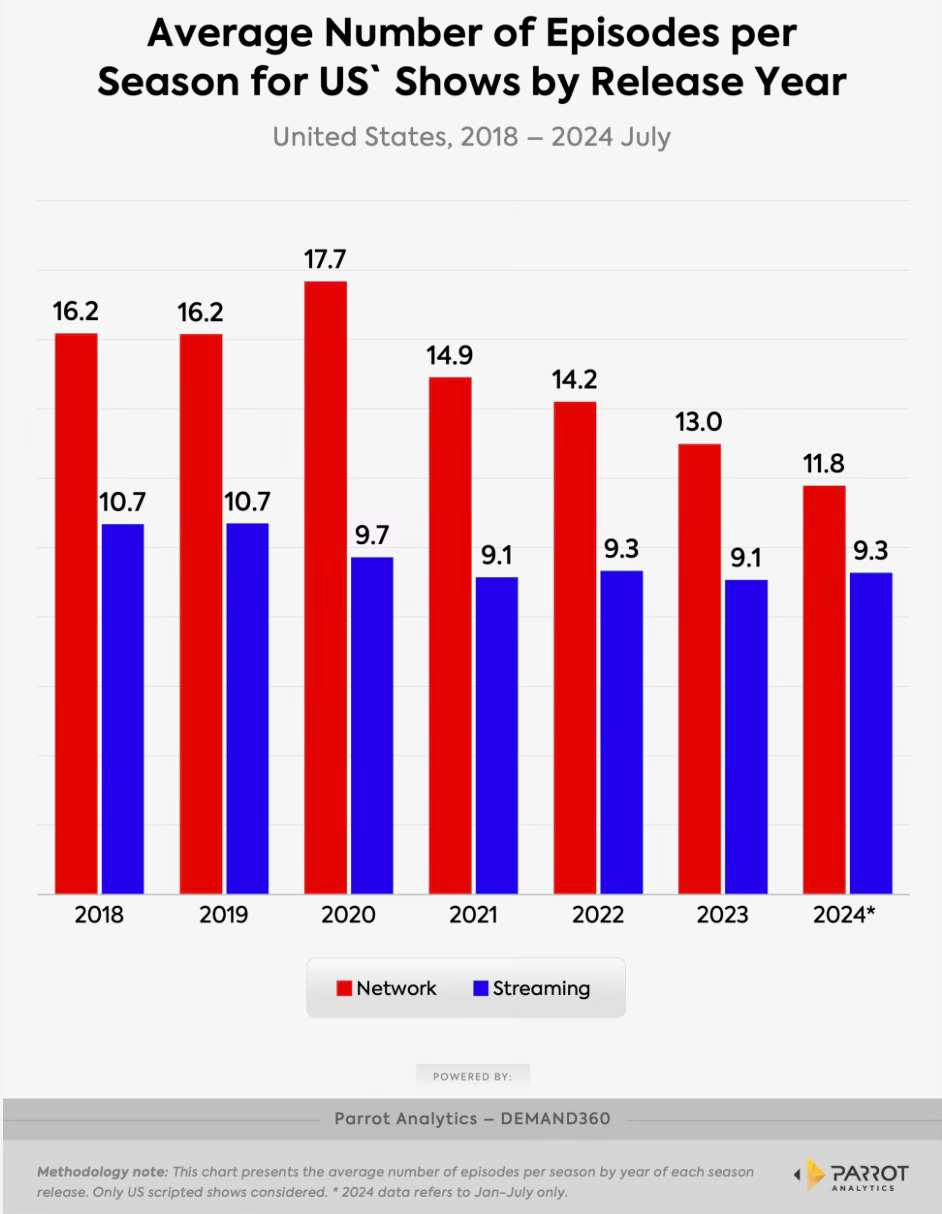

You don’t have to look far to see how shorter seasons and eight episode series have become the new norm. Titles like ‘Reacher’ and ‘Jack Ryan’ both have eight episodes per season, compared with a similar show from the semi-recent past, ‘24’, which ran for nine seasons with 24 episodes per season.

As Brandon Katz from Parrot Analytics outlines on TV Rev, the reduction in season length has been caused by multiple factors:

Rising production costs, declining linear ratings, plateauing subscription growth, rampant churn and a shrinking advertising market for linear are all major contributors. The economics of longer-running series are harder and harder to maintain these days. We’re two years removed from the concluding chapter of the low interest rate spending spree that fueled an entire industry to desperately chase Netflix’s juicy share price multiple.

As others noted in response to Marlon Wayans’ comments, the challenge remains to square the circle on how longer seasons can be funded, for example:

If people on X begging for longer run seasons are representative of genuine audience hunger (worth remembering X/Twitter makes up only around 10% of social media usage in the UK and US, so always a good pinch of salt whether noise on social reflects wider opinions), then maybe the next period will see the emergence of a new business model for the streaming age to deliver 20+ episode seasons to meet this audience demand.

For some, the rise of FAST (free ad supported TV like Tubi, Roku, Pluto et al) will ride to the rescue.

Which leads on to the next trend for this week…

The squeezed factual middle and the growth of FAST channels

The question of where and what is the middle of factual TV and why is it being squeezed has come up several times in the last few weeks. For those of us rather longer in the tooth than others, the call for low cost high volume and fewer bigger better titles has been a regular drumbeat for decades. As Stephen Lambert said in a recent Broadcast piece (£) called ‘How the indie sector is being turned inside out’:

has written a great long read for The Ankler/Series Business called ‘The Death of Mid-Budget TV’ (£) which outlines how the middle of UK factual TV hasn’t actually disappeared, rather the same type of content is still in demand but the tariffs have shifted downwards to the low budget territory.“Ever since I’ve been in television, people have said, ‘Oh, we’ve got to get rid of the middle.’ And finally, it’s happening. We’re moving towards big shows that make a real impact in a very crowded market, and then lots of lower-cost, high-volume shows. Buyers are ordering less of the mid-ranking shows than they ever have.”

In terms of tracking how much the factual TV market has changed over the past 15 years, the piece includes Channel 4’s Ian Katz describing mid-market TV as “gentle obs docs … about people giving birth or life in the zoo.” I assume (perhaps incorrectly!) this is a reference to ‘One Born Every Minute’, which was a ratings hit when it was first broadcast in 2009, won multiple Baftas and went on to run for 11 series as well as selling internationally (disclaimer, I worked on the multiplatform content for the first series). It is illuminating for what was a primetime returnable ratings success then to be seen as a mid market TV format now, thanks to the explosion in higher budget prestige and premium factual over the past 10+ years.

There appears to be international audience demand for mid-market factual, despite the challenges faced by the traditional broadcaster commissioning model. When looking at growing FAST platforms, mid-market titles are often staple offerings. Below is a screenshot of the EPG on Tubi US (the EPG functionality isn’t yet available on TubiUK), where shows such as ‘Kitchen Nightmares’, ‘Hell’s Kitchen’, ‘Jamie’s 15 Minute Meals’ and ‘Great British Menu’ are run on a 24 hour schedule (called ‘Live TV’ on the platform) with ad-breaks ever 15 minutes or so. Sort of a little like, you know, linear broadcast TV.

Distributors like Freemantle have been inking deals with platforms like Pluto TV where titles such as ‘Escape to the Country’ have their own FAST channels.

As a recent Business Insider piece on the rise of free TV in the US outlined, FAST is replicating a certain user behaviour that has long existed for linear TV:

A dirty little secret of the industry is that a certain amount of TV watching has always been passive. In other words, the set is left running in the background. Many FAST services offer a simpler way than paid streamers to passively watch. Some replicate linear TV channels that are easy to flip on, or they offer an array of news, entertainment, and sports just a few clicks away — no credit card or login required.

And as for FAST’s being the replacement for traditional broadcaster commissioning models: as noted last week when discussing Netflix’s journey to build an advertising tier, the central concern is that free ad-supported streaming TV won’t generate the revenues required to support the full range of programming- returnable formats, long running procedurals and sitcoms - in the same way broadcast TV has done for decades.

A comment this week from Fox Corp CEO Lachlan Murdoch (owner of Tubi along with Fox’s broadcast network) hints at this challenge, referencing the impact on surplus inventory and ad prices of Amazon flipping 200m users into their ad tier.

Both linear TV and FAST need new titles and talent rather than just relying on old factual favourites. This is where Faraz Osman’s observation in The Ankler’s piece is important:

…mid-market content is on its way to becoming the “entry-level” low-budget show. [Osman] also argues that in reality the real entry-level commissions, often meted out to new producers, are now digital shorts with new talent, which have micro budgets.

Maybe this is just the latest incarnation of the ladder for new formats, fresh talent and green production companies to climb - with digital shorts proving a way to test out a format or talent, which can then quickly transition to a series whether commissioned or distributor/brand funded, albeit at a lower price point. And sure, you can probably make some mid-market titles for less, but for many titles there simply isn’t much space for squeezing and retaining a profit, especially highly sensitive and therefore editorially challenging precincts like hospitals, schools, police stations and the like.

With the middle being squeezed for linear and concern that FAST advertising may not deliver the revenues required to finance production budgets, The Ankler piece highlights how distributors and brands are increasingly stepping in to fund the mid-market factual formats. Even so, the downward push on budgets and increasing complexity in getting titles funded remains, and in both The Ankler and Broadcast pieces, seasoned industry voices questioned in practice how sustainable and profitable this can be, especially for newer companies.

Re-discovering romantic comedies and melodramas

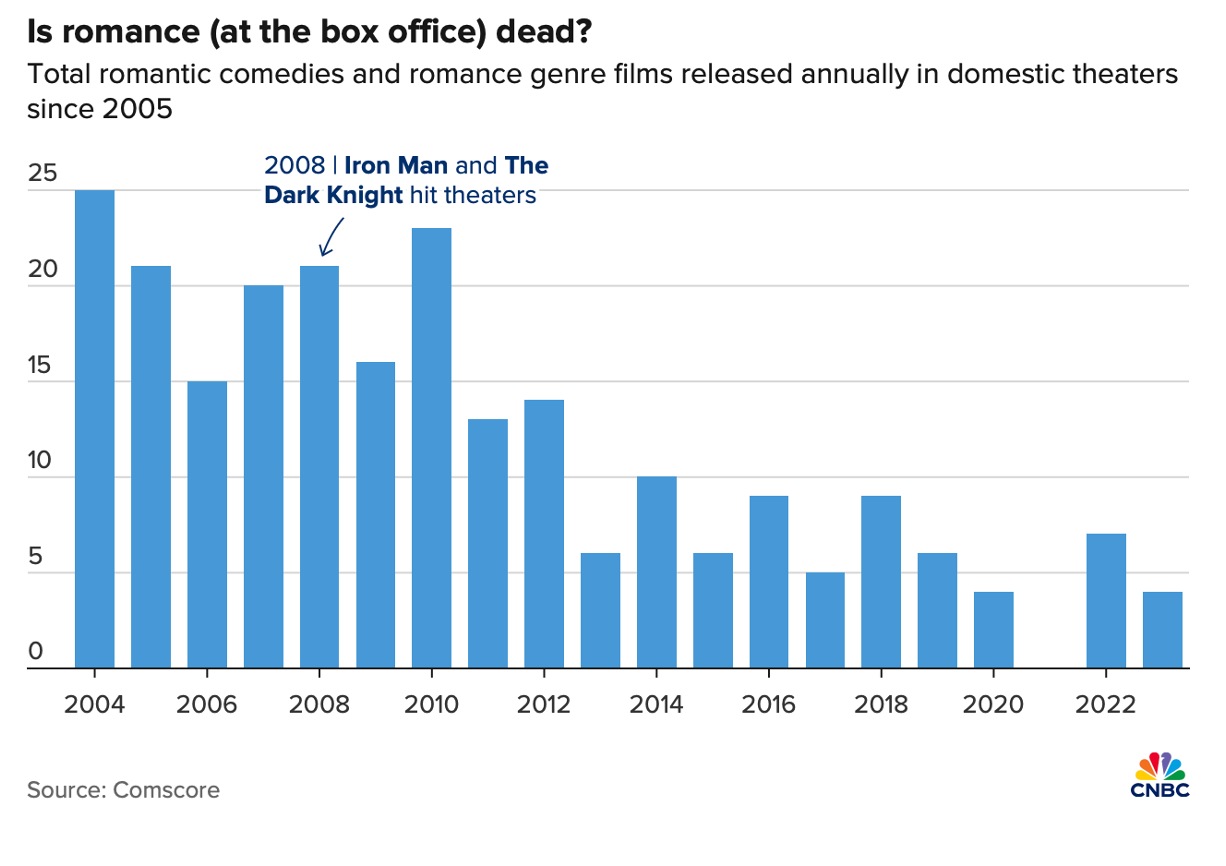

It isn’t just nostalgia talking when there is a sense films like ‘Beaches’, ‘Pretty Woman’ and ‘When Harry Met Sally’ just aren’t made any more. Female skewing films - rom coms and melodrama - have been notable by their absence in the last twenty years, following the rise of juggernaut franchises.

In May last year, Netflix shelved the queen of romantic comedy Nancy Myers’ new film (rumoured to have Scarlett Johansson and Michael Fassbender attached), following suggested concerns over a $130m budget.

However, it appears this trend is reversing, as Hollywood re-discovers what (some) women want and the relatively small budgets these titles require. Leading the charge late last year was ‘Anyone But You’ starring Sydney Sweeney and Glen Powell. A slow burn hit, it went from $6m box office sales for its first weekend, to doing $220m globally (from a rumoured $25m production budget).

And more recently, ‘It Ends With Us’, the $25m adaption of the Colleen Hoover novel, has grossed $288m in its first month alone. In the film’s first weekend, Sony said 84% of ticket buyers were female, and of the total audience, they were also young (60% were 18 - 34) and ethnically diverse. And around half were infrequent movie goers. If you have spent any time on BookTok, the smash success of this film would not come as any surprise, as Colleen Hoover is absolutely enormous on the platform.

(At some point, I’ll do a separate piece on how TikTok and BookTok in particular can drive audiences based on working with publishing sector and what TV and film can learn from this).

So while it can be assumed this particular author brought these people to the cinema for this film, that so many were infrequent movie goers does pose a wider ‘which came first’ conundrum. Did they stop going because there weren’t any films they wanted to see, or were the films they wanted to see stop being made and therefore they stopped going?

In days gone by when there were fewer choices on how to spend leisure time, perhaps studios had more leeway to leave audiences wanting, safe (or safer) in the knowledge that people would take what they were given. Now there is a wealth of options for how to spend our free time, the danger in not giving people what they want is to risk habit-breaking. So people stop going to the cinema, or reading a book, or watching live TV, or going to a concert, and instead find something else they prefer. Social video or gaming, or the myriad of other options out there. Perhaps never to return.

Breaking habits

Putting these three trends together brought to mind the concept of the ‘trust thermocline’ - as outlined by John Bull on Twitter several years ago. You can read his whole explanation here, but in a nutshell, it is the idea that users suddenly bulk abandon a product or service and it isn’t clear what caused this mass rejection. But actually, what has happened is people have swallowed the minor changes, the price increases, the cancellation of a much-loved series or two, the lack of sitcoms or longer procedurals, the reduction in films for ‘people like me’, all the while building a perhaps subconscious sense of being taken for granted, until suddenly, they say ‘no more’! And once trust and the associated habits are gone, well, they are very hard to get back.

As John explains:

Users and readers will stick to what they know, and use, well beyond the point where they START to lose trust in it. And you won't see that. But they'll only MOVE when they hit the Trust Thermocline. The point where their lack of trust in the product to meet their needs, and the emotional investment they'd made in it, have finally been outweighed by the physical and emotional effort required to abandon it.

Or as Hemingway wrote in 1926:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

That’s it for this week - speaking of the Wayans family, I’ll leave you with this lovely clip from 1991 of Keenen Ivory Wayans paying tribute to his comedy hero, Richard Prior.

Follow @businessoftv on Twitter/X, say hi via email hello@businessoftv.com, or connect with me on LinkedIn.