Google's antitrust case loss - what could it mean for TV; huge write-downs of US cable TV nets; some car creators abandon YouTube

Google’s loss of the antitrust case

The antitrust trial lost by Google this week will have major implications not just for the company itself and the tech industry, but also for TV and media ownership in the US. Unsurprisingly, this will then have knock-ons to the UK TV production and distribution markets.

For the owner of YouTube (which has the biggest streaming video audience share) to be judged a monopoly is big news, and whether (and how) the company is broken up in the future will have significant ramifications.

And that is before the outcome of the antitrust case brought by Fubo against Disney, Fox and WBD’s sports joint venture Venu, or other antitrust cases that may come in the future. This does seem to mark the start of a new phase of tighter regulation on mergers and consolidation, although obviously that can all change depending on who sits in the White House.

Entertainment Strategy Guy has done an excellent piece analysing the US TV sector, and then goes on to suggest a plan for how the market could be regulated. As he says:

I’ve been on “pro-competition” since I went to business school. Indeed, I feel strongly that our economy, in general, and our industry (Hollywood), in particular, needs competition more than ever…. I want to convince as many people in Hollywood to join me in protecting markets, especially since it’s the most pro-worker policy out there. If we want a better Hollywood, we need a more competitive Hollywood.

Called ‘Here’s A 7 Point Plan To Save Hollywood Workers And The Marketplace’, it is a rallying call to the TV and film industry to get to grips with how serious the level of consolidation is within the market - vertically, horizontally and via new tech platforms - and how that has not been positive for competition, consumer choice and creators especially.

He’s highlighted that the UK market is a great model for how interventions can foster more competition to the benefit of producers and audiences. This piece from Matt Stoller in 2023 suggests Hollywood should take inspiration from the UK’s terms of trade. Stoller wrote: ‘Put simply, governments changed laws so that independent producers gained bargaining leverage in the UK, and lost it in the US’.

I would recommend reading ESG’s full piece - is free outside the paywall (and if you have some spare cash, a paid subscription is money well spent), but as he has encouraged people to share his plan far and wide, I’ve included his seven strategies in full below. Some of the fixes on his plan have been talked about for decades (or at least, the issues they are addressing have been warned about for some time), so it will be interesting to see if there is any traction for these types of market interventions:

Eliminate any parts of the value chain with horizontal consolidation. More competitors leads to lower prices. Most of the theorizing about economic efficiencies and economies of scale hasn’t borne fruit. So consolidation in theaters, talent agencies, industry trades, broadband and cellular distribution, and elsewhere should be addressed by antitrust enforcers.

Bring back the “FinSyn” rules for the 21st century. Short for “financial syndication”, this meant that broadcast networks couldn’t own the majority of shows airing on their channels. A new rule like this would force the streamers to buy from third-party producers, which would be a boon for talent. It would also likely improve the quality of shows, since it would lead to a much more competitive market.

Severely limit vertical integration, especially if different parts of the value chain can create value for customers. While we’re at it, put in rules that any distributor (think Apple, Amazon, Google and Roku) can’t also own a streamer. That would avoid conflicts of interest on app stores, and level the playing field. This avoids the temptation to extract profits in one part of the value chain at the expense of another.

Cap platform taxes everywhere. Apple charges people 30% to sell things in its app stores. Google and Amazon and Roku too. (Though they do provide tax breaks to very large corporations in a surprisingly regressive tax move.) These taxes on businesses are just ridiculously high, which is why all the stores have such high operating margins. These caps would flow directly to either streamers (to spend on content) or to customers (in terms of lower prices). Given how little Apple and Google spend on their app stores—again look at the profits—you’d hardly notice a change in the stores, except for lower prices.

Oh, break up Big Tech, especially the video platforms. I don’t know if Apple TV+ and Amazon’s Prime Video make money, but I’d love for them to exist on their own to compete in the market on their merits. Same for YouTube, which benefits tremendously from Google search traffic. So if the above rules preventing vertical integration don’t happen, we should still break up Big Tech to make everyone compete on the same playing field to woo customers.

Break up entertainment conglomerates. Yeah, I’m going there too. The above rules would encourage breakups among the production and streaming arms of entertainment companies, but if not I’d explicitly do that too. I’d also break up the movie theater chains to spur innovations in that small part of the ecosystem. Oh, the agencies too.

Address piracy and IP theft. Once Big Tech has less political power, mandating that platforms stop promoting pirated content seems like an easy policy to demand.

In a similar vein, the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA) published a report in 2021 called ‘Broken Promises’, which was hugely critical of the impact of media consolidation where promises are made before mergers and then are simply not kept. They say mergers are talked up as being good for consumers and the market, however after the deals are done, the results are further consolidation and reduction in diversity of supply, which negatively impacts audiences and the workers with the TV and film industries.

They have recently published an update to the above report, to reflect how the Warner Bros. Discovery merger affected audiences and workers. The update says:

The series of mergers that led us here—first the $85 billion AT&T-Time Warner merger and then the $43 billion WarnerMedia Discovery merger—have each promised to create a better competitor, but have instead left the merged entity debt-burdened and focused on cutting costs to rationalize these disastrous business decisions. Yet media’s merger mania shows no sign of slowing; the latest industry speculation is that Comcast may next seek to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery. Absent government intervention, this cycle of reactive consolidation will likely continue until it leaves just three or four companies controlling all content, while content creators and consumers pay the price for these costly mergers.

Entertainment Strategy Guy: ‘Here’s A 7 Point Plan To Save Hollywood Workers And The Marketplace’

Read the updated WGA report into the Warner Bros. Discovery merger.

Cable TV’s huge write-downs

Both Paramount Global and Warner Bros. Discovery announced enormous write-downs in the value of their linear channels last week - $6bn for Paramount and $9bn for WBD.

These announcements weren’t unexpected, and yet the size of the sums involved and the response from various publications did result in a sharp intake of breath. After years talking about what the future could look like, it does feel like 2024 is when that future is becoming a reality. Here are some great pieces to read on these write-downs:

Big Media Can’t Hide From Hard Decisions on Cable Valuations Any More (Variety)

Paramount's TV networks are collapsing in a $6 billion hole (Business Insider)

Media companies finally admit the cable business is collapsing (Lucas Shaw’s weekly Bloomberg Screentime newsletter, around half way down the page).

To pick up on one assumption that caused a little flurry of discussion online. The Axios piece includes the following sentence:

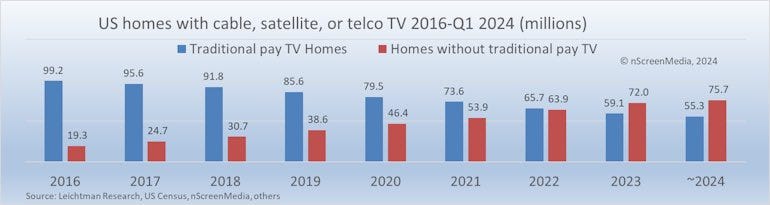

While cable is challenged, analysts believe there will be a loyal set of pay-TV customers — around 50 million households — for the foreseeable future, thanks to cable networks like ESPN that still own live sports rights.

However, some people questioned where the idea of 50m households comes from. Was it realistic or an off-the-cuff remark that may have shaky foundations and in reality the number might be lower?

Jeff Bewkes, the then chairman and CEO of Time Warner Inc made a very astute observation in a piece by Alex Sherman back in 2020, when asked if the smaller players (such as traditional studios and cable networks) can compete against Netflix, Amazon and Apple:

“The answer is no,” said Bewkes. “These companies are competing against Netflix and Amazon, who have massively more scale for both subscription and advertising at a global level. They’re all going to be collapsed. Only Disney will have enough subscribers and global scale under a distinctive family brand to make it.”

(The whole 2020 article by Alex Sherman is worth reading, as it includes many predictions that are now becoming a reality).

And if you want a visual representation of why these write-downs have happened, then the following tells the story:

As for what’s next for WBD - well, there are many hypotheses. Just a few weeks ago it was suggested the operation might be broken up and sold. Now the rumour is selling smaller assets. And next week perhaps another rumour…

One suggestion for the whole corporation to be bought - Peter Kafka of Business Insider has made (a slightly tongue in cheek?) case that Apple should buy the whole thing, doing a back-of-an-envelope calculation it would cost Apple around $70bn (making the point that is what Microsoft paid for games company Activision a few years ago). For that they would get HBO to bolster Apple TV plus a stable cable TV channels, all for a much cheaper price than several years ago. However, whether that would get past antitrust rules is another matter.

YouTube car creators quitting

The Verge has published a fascinating article about how car YouTube creators have abandoned the platform after building successful channels. It is a familiar story - the power of the internet to connect enthusiasts with each other, and enable a handful of these superfan creators to build significant audiences on their own channels and become mini (or not so mini) digital media brands in the process. These creators and their media brands then attract the interest of larger companies who buy them, and in the process the original authenticity and passion is lost and instead creators feel like they’ve become slaves to both the YouTube algorithm as well as their new corporate owners.

If sometimes YouTube feels like an attractive places to operate for TV producers who haven’t yet dabbled their toes in the water, then the following sentence might be a little sobering:

YouTube paid out an astonishing $70 billion to creators in the past three years. However, it has 113.9 million active channels, according to Global Media Insight. That works out to roughly $200 per creator per year if you portion it out evenly — but of course, it’s the top channels earning the vast majority of that revenue.

The Verge: Why are so many car YouTubers quitting?

Other odds and sods

NBC used AI to generate daily voiceovers to recreate iconic sportscaster’s Al Michaels’ voice for daily recaps (Vanity Fair)

Hallmark TV has announced its launch slate - while this may not yet be a go to commissioner for UK production companies, it is an interesting proposition to keep your eyes on as a) it is a new streamer launching when others are having a wobble and b) the idea is heavily integrated into Hallmark’s existing retail offering (read a summary of the concept in a previous post).

The success of Sony-owned anime streamer Crunchyroll in targeting global superfans has been covered by The Wrap. (Lucas Shaw from Bloomberg noted that “WarnerMedia sold the anime service Crunchyroll when it had a few million subscribers. Crunchyroll now has 15 million subscribers and is a multibillion-dollar business”).